ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΕΣ ΕΠΙΡΡΟΕΣ ΣΤΗΝ ΣΟΓΔΙΑΝΗ & ΤΗΝ ΕΥΡΥΤΕΡΗ ΠΕΡΙΟΧΗ

Οι Σογδιανοί της πρώτης χιλιετίας μ.Χ. δημιούργησαν το πιο σημαντικό και επιδραστικό μη βουδιστικό ιδίωμα εικαστικής τέχνης στην προ-ισλαμική Κεντρική Ασία. Η αξία της Σογδιανής τέχνης έγκειται στην ανάπτυξη ενός εξαιρετικά πλούσιου συνόλου παραστατικών εκδοχών για την απεικόνιση θεοτήτων, πνευμάτων και δαιμόνων, οι περισσότεροι των οποίων είναι Ζωροαστρικοί. Οι πρωταρχικές τους ρίζες είναι η Ελληνιστική κληρονομιά, αλλά και οι θρησκευτικές εικόνες του Κοσσανικού κόσμου με τα ισχυρά Ινδικά στοιχεία τους.[2] Ο Reck μάλιστα αναφέρει σχετικώς:[2a]

Η θρησκεία των Σογδιανών στην πατρίδα τους περιγράφεται ως ένα είδος «θρησκείας της πόλεως» παρόμοια με την κατάσταση στην Κλασική Ελλάδα (Shenkar 2017). Τα περισσότερα χαρακτηριστικά αυτής της θρησκείας μπορούν να συναχθούν από πίνακες και άλλα καλλιτεχνικά αντικείμενα (Mode 2003; Grenet 2015b).

Υποστηρίζεται ότι οι πλείστες πόλεις - κράτη της Σογδιανής διοικούντο από ηγεμόνες οι οποίοι όμως εξελέγοντο ή κατηργούντο από την κοινότητα, δηλαδή έμοιαζαν περισσότερο με Έλληνες βασιλείς παρά με Ασιάτες δεσπότες. Σύμφωνα με τον Marshak υπάρχει μεγάλη ομοιότητα μεταξύ του Σογδιανού και του Ολυμπίου πανθέου. Η Zemat θεωρείται ότι αποτελεί μεταφορά της Δήμητρας μέσω Βακτρίας, εν γένει δε η Σογδιανή θρησκεία - με διαφοροποιήσεις κατά πόλη - τροφοδοτήθηκε από την Μεσανατολική / Μεσοποταμιακή παράδοση, την Ελληνική και αυτήν του Ζωροάστρη.[3]

Worshipers from the Northern Shrine of Temple II, Panjikent

Dilberjin Tepe, Athena Anahita

Frescoe: 7th-8th century artist. Photographs: Irina Gruklikova - Fouilles de la Mission Archaeologique Sovieto-Afghane

ΑΠΟΣΠΑΣΜΑ Α'[5]

that the figure depicted on the terra-cottas is the same figure depicted on the Panjikent wall paintings.

The Sogdian cithara player has been compared to the god Apollo,[27] but it is most unlikely that a Greek god appears on the terra-cottas on which a seated figure is shown playing this instrument. The Sogdian musicians are much closer to the many representations in Late Antique and early Byzantine art of a seated Orpheus [28] who, as a Thracian, was depicted by artists as a barbarian wearing garments resembling those of a Parthian or of the local nobility of Roman Syria.[5a1] In the early third century. Flavius Philostratus[5a2] described the image of Orpheus in Parthian Babylonia: "They are, by the way, favorably disposed toward Orpheus more for his tiara and wide trousers than for his skill in playing the cithara or singing, which had such an enchanting force. [29] A reinterpretation of this image in Judaic land (subsequently in early Christian) art as King David [30] facilitated the conversion of a seated cithara player in Oriental clothes into a Sogdian regal deity. The Sogdians learned about Christianity primarily from Nestorian missionaries [ΝΕΧΤ COLUMN] from the Sasanian Empire. Among the early Christians, Orpheus represented Christ, while David was a prototype of Christ. Occasionally Orpheus, seated on a throne in a royal Sasanian pose with splayed knees and surrounded with beasts and mythological monsters shown listening to him reverently, appears as the Almighty {ΠΑΝΤΟΔΥΝΑΜΟΣ}.[31] However, such compositions, which were not Christian images, were interpreted merely as allegories. Sogdians in search of iconographic images could turn to Orpheus imagery without fear of being mistaken for Christians. In doing so, the Sogdians not only emphasized the features that already resembled a Sasanian king in the prototype but also depicted a seated cithara player on a throne with elephant supports, [32] which, like all zoomorphic thrones of the gods, certainly carried a symbolic meaning. [33] In Sogdiana, each deity had a corresponding animal on which he might be shown riding; his throne might resemble the supine animal or he supported by such animals. All three variants are equivalent in Sogdian art, so that a zoomorphic throne may be regarded as similar to a vahana, the vehicle of an Indian god.

Dilberjin Tepe, Athena Anahita in profile

Frescoe: 7th-8th century artist. Photographs: Irina Gruklikova ΑΘΗΝΑ - ANAHITA σε τοιχογραφία στο Dilberjin

ΑΠΟΣΠΑΣΜΑ Β'[6]

As a matter of fact, the Sogdians equated their gods to the Indian gods and, for example, likened their own Adhag to Shakra (Indra), whose vahana was the elephant. [34] Such comparisons, reflected in Sogdian Buddhist texts, arose in a Buddhist environment, but the Panjikent representation of the god Veshparkar, identified with Mahadeva [Shiva], indicates that they also influenced the local non-Buddhist iconography. [35] Thus, the god with the cithara or lyre may be Adbag, equivalent to lndra, the Indian lord of the heavens, Ahura Mazda himself appears in Sogdian texts under the name of Adhag. [36] Could the cithara player in our mural be so exalted a deity? In scale he is larger than the supposed Vashagn and stands in front of him. The royal ribbons issue from his crown, and there are equally long ribbons on his boots, in contrast to the costume of Vashagn. Ribbons on boots of this type could have no functional purpose but instead must have been adopted from Sasanian costume as a royal attribute. Yet, could a god of so high a rank as Adhag be an intercessor before the four-armed goddess?

Interpretation of the Northern Wall Mural

The obviously metaphorical trophy of Vashagn suggests that the painter depicted not the gods themselves but actors playing their parts. And here, the actor-gods are shown on a larger scale (close to that of the figure of the goddess) than the minor figures who portray mere mortals. There is no analogy in the royal costume to the strange ungirded clothes of "Adbag" cut at the lower edge into four long, pointed triangular pieces. Perhaps, like the varying buckles an the boots, they are specific details of an actor's attire, which could be rather extravagant, as demonstrated by the painting of Sogdiana and eastern Turkestan. An-other example is a garment with four triangular sections trimmed with bells at the lower edge

..

When creating their cultic iconography in the fifth-sixth centuries AD, the Sogdians turned to foreign models, of India and Greece (Silenus, Athena, Heracles, and others) and, occasionally, Kushan Tokharistan. All these models underwent change under the influence of Sasanian art, probably in areas controlled by the Kushano-Sasanians. This occurred both under the Sasanians and later, under the Kidarites and the Hephthalites, throughout the fourth-sixth centuries AD. From these sources came the poses of the enthroned goddesses, the typically Sasanian wavy ribbons, and other characteristics of cultic compositions. [37] However, despite these borrowings, the Sogdians pursued their own identity, representing in concrete, distinct depictions a multiplicity of gods worshiped by individual families and communities. Rather than portraying the major Buddhist, Christian, or Manichean images, they found it suitable to borrow the mi-

FIG. 3-6. Detail of Jug: figure playing pipa. Tibet or Sogdiana, 7th–8th century. Silver with gilding, H. approx. 80 cm. Lhasa Jokhang, Tibet.

ΑΠΟΣΠΑΣΜΑ Γ'[7]

This series also includes the goddess on a lion,[71] the god on the camel throne,[72] and the goddess resembling Athena (the latter has been recorded in painting only in Tokharistan). [73] The Tokharistan mural from Dilbarjin with the goddess who resembles Athena, like the figures examined here, demonstrates an interpretation of the Classical heritage under the impact of Sasanian art.

Μη-σογδιανά όργανα, όπως η ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΤΙΚΗ λύρα/κιθάρα, απεικονίζονται να παίζονται από τους θεούς, πιθανώς ακόμη και από τον ίδιο τον Αχούρα Μάζντα. Αυτά τα όργανα και το ινδικό τόξο εμφανίζονται σε μερικά από τα μεταγενέστερα έργα, δείχνοντας την επιρροή των Δρόμων του Μεταξιού στην ίδια τη Σογδιανή μουσική.[10]

ΣΚΗΝΗ ΘΡΗΝΟΥ (ΓΙΑ ΤΗΝ ΑΠΩΛΕΙΑ ΤΗΣ ΠΕΡΣΕΦΟΝΗΣ ?) ΜΕ ΤΗΝ NANA & ΤΗΝ ΔΗΜΗΤΡΑ ΑΠΟ ΤΟΙΧΟΓΡΑΦΙΑ ΤΟΥ ΙΕΡΟΥ ΙΙ ΣΤΟ PANJIKENT[15]

Τοιχογραφία 'θρήνου' από τον νότιο τοίχο της κύριας αίθουσας του ιερού II[17]

Αυτή η αποσπασματική τοιχογραφία από την κύρια αίθουσα του Ιερού II στο Panjikent είναι μια από τις πιο γνωστές ανακαλύψεις από τα πρώτα χρόνια της συστηματικής ανασκαφής της πόλεως στα τέλη της δεκαετίας του 1940. Μια ζωηρή και πολύπλοκη σύνθεση απεικονίζει τον θρήνο για τον νεκρό, ο οποίος [θρήνος] είναι ορατός μέσα από τις τρεις τοξωτές καμάρες μιας θολωτής κατασκευής. Το σώμα είναι ενδεδυμένο στα κόκκινα με μακριές τρέσες και περίτεχνη κόμμωση. Μέσα από τις καμάρες μπορούμε επίσης να δούμε τρεις γυναίκες που θρηνούν να σκίζουν τα μαλλιά τους, ενώ από κάτω θρηνούν και άνδρες και γυναίκες, με τους άνδρες να κόβουν τα γένια τους. Στα αριστερά της συνθέσεως εμφανίζονται τρεις μεγαλύτερες μορφές. Η μεγαλύτερη είναι μια όρθια θεά με φωτοστέφανο, με τέσσερα χέρια, δηλαδή η NANA, στα δεξιά της, μια άλλη μορφή με φωτοστέφανο, που δεν έχει ακόμη αναγνωριστεί, γονατίζει και φαίνεται να σκουπίζει το έδαφος μπροστά στη όρθια θεότητα. Πίσω τους στέκεται μια τρίτη μορφή, με το αριστερό της χέρι σηκωμένο και το δεξί να κρατά άγνωστο αντικείμενο.[20]

ΣΗΜΕΙΩΣΗ: Η μή αναγνωρισθείσα [σύμφωνα με την Ιουδήθ Judith A. Lerner & το Ίδρυμα Λεβή - Leon Levy Foundation - γνωστό ως υποστηρίξαν τον Cίπρα ..][21] ταυτοποιείται σύμφωνα με τους Grenet & Azarnoush με την Ελληνίδα θεά ΔΗΜΗΤΡΑ![22] Αλλωστε το όνομα της Δήμητρας έχει πιστοποιηθεί ότι εχρησιμοποιείτο από Σογδιανούς ως θεοφορικό. Π.χ. το όνομα Jimatvande, γνωστό Σογδιανό όνομα σημαίνει τον 'υπηρέτη της Δήμητρας"

Zymtyc, the 11th month of the Sogdian calendar, is named after a god Zymt, who is mentioned in the name Shewupantuo (29) (*dźi̯a mi̯uət bʻuân dʻâ; Ikeda, 1965, p. 64) = zymt-βntk. In the light of its Bactrian counterpart drēmatigano, Sims-Williams (2000, p. 190) proves that the god originated from the Greek earth goddess Demeter. A Middle Persian loanword for “Tuesday” is found in the name Wenhan (30) (*˙˙uən xân, cf. British Library MS S. 542, line 74; Ikeda, 1979, p. 537) = wnxʾn.[30]

Το Zymtyc, ο 11ος μήνας του Σογδιανού ημερολογίου, πήρε το όνομά του από έναν θεό Zymt, ο οποίος αναφέρεται στο όνομα Shewupantuo (29) (*dźi̯a mi̯uət bʻuân dʻâ; Ikeda, 1965, σελ. 64) = zymt-βt. Υπό το φως του αντίστοιχου της Βακτριανής drēmatigano, ο Sims-Williams (2000, σ. 190) αποδεικνύει ότι ο θεός προέρχεται από την ελληνική θεά της γης Δήμητρα. Encyclopaedia Iranica, s.v. PERSONAL NAMES, SOGDIAN i. IN CHINESE SOURCES

Κεραμεικό σύμπλεγμα δύο καθήμενων γυναικών, πιθανώς Δήμητρας - Περσεφόνης[32]

----------------------------

This fragmentary wall painting from the main hall of Temple II in Panjikent is one of the best-known discoveries from the early years of systematic excavation of the city in the late 1940s. A vivid and complex composition depicts the lamentation for the deceased, who is visible through the three arches of a domed structure. The body is dressed in red with long tresses and an elaborate headdress. Through the arches we can also see three mourning women tearing their hair; below, men and women also mourn, with the men cutting their beards. To the left of the composition appear three larger figures. The largest is a standing, haloed, four-armed goddess; to her right, another haloed figure, yet to be identified, kneels and seems to sweep the ground in front of the standing deity. Behind them stands a third figure, her left arm raised and her right holding an unidentified object.[40]

----------------

Finally, there were elements foreign to the Iranian religion, nevertheless integrated into the festive calendar: the Mesopotamian cult of Ishtar, called Nana in Central Asia, and a surprising discovery made in recent years, a CULT OF DEMETER associated with the cult of Ishtar in seasonal celebrations. This transplantation of the mysteries of Eleusis can only be identified as a legacy of the Greek era, even if no Greek coin from Bactria includes the image of the associated divinities...[45]

-------------

THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY: An Introduction to Uzbekistan ... Although much of what we know about Zoroastrianism today was codified by the Sasanians, it is likely that the religion that the Sogdians and other Central Asian peoples practiced was a slightly broader version of old Iranian religion, which included the worship of the god Ahura Mazda, and at times included worship of the Greek goddess Demeter and the Hindu god Shiva.[50]

---------------------------------

7 Luckily the epitaph of a Sogdian with the same clan name Shi 史, likely representing their original city-state Kish in Central Asia, contained a segment inscribed in Sogdian that cited a personal name δrymtβntk/ Žēmatvande, which according to Yutaka Yoshida was, if not the same 射勿槃陀, at least a namesake. 38 Nicholas Sims-Williams further interprets the Sogdian name as “slave of Demetra.” 39 The deity Demetra/Demeter, representing the eleventh month of the Sogdian and Bactrian calendars, was originally the Greek goddess of agriculture, which makes this a case of Sino-Greco-Sogdian cultural fusion in the medieval Chinese onomasticon, adding a Hellenistic touch to the Iranization of Chinese nomenclature.[55]

--------------------

Η περίφημη 'σκηνή του θρήνου' που περιλαμβάνεται στον ζωγραφικό διάκοσμο της τετράστυλης αίθουσας του Ιερό II στο Panjikent χρονολογείται από τον 6ο αι. Ανακαλύφθηκε το 1948 και επανεξετάζεται υπό το πρίσμα πρόσφατης έρευνας. Η τετράχειρη θεά που αναλαμβάνει τον κύριο ρόλο προσδιορίστηκε από την αρχή ορθώς ως η Νανά, αλλά το θεμελιωδώς μεσοποταμιακό υπόστρωμα του τελετουργικού που απεικονίζεται στη σύνθεση φαίνεται πιο καθαρά από μια ενδελεχή ανάλυση δύο σχετικών κειμένων: τα Απομνημονεύματα του Κινέζου απεσταλμένου Wei Tsie (που το περιγράφει στην Σαμαρκάνδη, με σαφή αναφορά στο Tammuz) και το πολεμικό μανιχαϊστικό απόσπασμα M 549 (που το καταδικάζει). Σε αντίθεση με τη συχνή πεποίθηση, η ξαπλωμένη σωρός πάνω στο οποίο θρηνούν η θεά και οι άνδρες είναι αυτό μιας νεαράς γυναίκας. Πρόκειται κατά πάσα πιθανότητα για την Gestinanna, αδελφή του Tammuz, η οποία στον μύθο της Μεσοποταμίας αντικαθιστά τον αδελφό της στον κάτω κόσμο αρκετούς μήνες τον χρόνο. Στην Σογδιανή εκδοχή η εικόνα της είχε ίσως συγχωνευθεί με αυτήν της Περσεφόνης, καθώς μια νέα ανάγνωση του μανιχαϊστικού κομματιού από τον Ν. Σιμς-Γουίλιαμς δείχνει την Δήμητρα να συναναστρέφεται με τη Νανά στο πένθος. Τέλος, μερικά άλλα εικονιστικά έγγραφα από την Σογδιανή και την Βακτρία δείχνουν την Νανά να σχετίζεται με έναν θεό τοξότη. Προτείνεται να ταυτιστεί με τον Tistrya-Tir, Ιρανό θεό του πλανήτου Ερμού, ο οποίος είχε αναλάβει τις λειτουργίες του Βαβυλωνιακού Nabu, θεού της γραφής, της εγγραμματοσύνης και της επιστήμης.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The famous "scene of mourning" included in the painted decoration of the tetrastyle hall of Temple II at Panjikent dates from the VIth c. A.D. Discovered in 1948, it is reexamined in the light of recent research. The four-armed goddess who assumes the main role was from the beginning correctly identified as Nana, but the fundamentally Mesopotamian substratum of the ritual depicted in the composition appears more clearly from a thorough analysis of two relevant texts : the Memoir of the

Chinese envoy Wei Tsie (who describes it at Samarkand, with a clear reference to Tammuz) and the polemical Manichaean fragment M 549 (which condemns it). Contrary to frequent belief, the lying corpse upon which the goddess and the men are lamenting is that of a young lady. She is in all probability Gestinanna, Tammuz 's sister, who in the Mesopotamian myth replaces her brother in the underworld several months a year. In Sogdiana her image had perhaps fused with that of Persephone, as a new reading of the Manichaean fragment by N. Sims-Williams shows Demeter associate with Nana in the mourning. Lastly, some other figurative documents from Sogdiana and Bactria show Nana associated with an archer god. It is proposed to identify him as Tistrya-Tir, the Iranian god of the planet Mercury, who had assumed the functions of Babylonian Nabu.[60]

---------------------

The Hellenistic cultural factor continues in acceptance and imitation. The ancient city of Pianchi Kent [Pendjikent], built in the 5th century AD, is relatively well preserved. Although more than 6 centuries have passed since the end of the Greek rule in the mid-2nd century BC, both the architectural style and the content of the murals are of Hellenistic culture. The strong proof of the remains of Sogdiana proves the continuation of Hellenistic cultural factors in Sogdiana, and the Hellenistic cultural factors are mainly manifested in the use of some details and image forms.

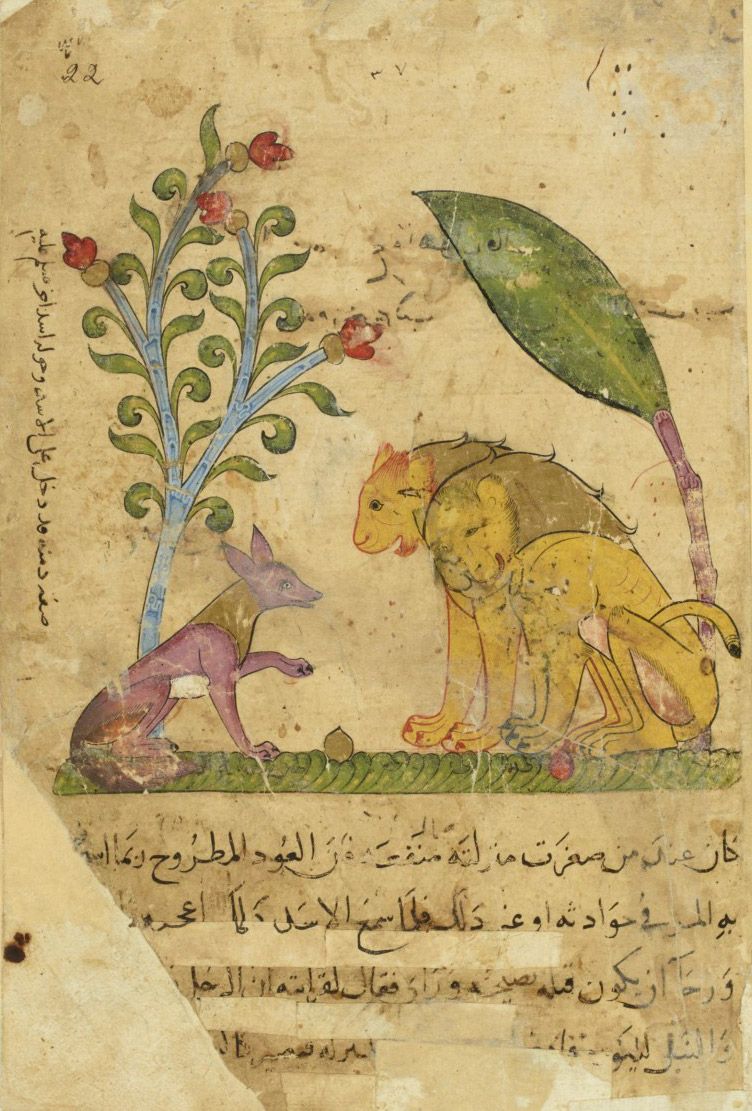

Απεικόνιση μύθων του Αισώπου[62]

The appearance of the story of Aesop's Fables on the frescoes is an example of Sogdiana's Hellenistic influence. Room 41/6 reflects the 53rd fable in Aesop's Fables, Father and Son, depicting a father admonishing his sons that brothers are like a bundle of sticks, if together they are It is not easy to take apart, but if they are independent, they are easily defeated by the enemy. Room 1/21 reflects the fables "The Goose Laying the Golden Egg" and "The Lion and the Rabbit". There are other examples of classical themes in the frescoes, but some are unclear in imagery, and some may be completely Sogdian in the costumes, so it is difficult to discern.

On the frescoes on the north wall of the hall, there is a picture of "Feasting Figures", which depicts "four people sitting in pairs, wearing knee-length silk robes, sitting on a splendid blanket, holding golden Laitong cups, some of which are horn cups. Bird heads, some blue sheep. One holds a bouquet of flowers with bare hands, the other wears a fur hat with colorful fringing, watching the flower bearer. Another is turning his head back, holding up a The wine in his hand is pouring from the corner glass, and it just falls into the mouth." The Greek god Demeter appears in the fresco mourning scene, and Demeter also

{see figure below!}

The form appears in the Sogdian calendar and is used to denote the month of November. In addition to the above-mentioned Hellenistic features, the figurative and pictorial features on the walls are also part of the Hellenistic cultural heritage. The heads of the figures on the frescoes show a typical three-quarter scale, with a certain distance between the figures and less overlap. Mural art uses the "Boundary Breaking Method", that is, "the wall is divided up and down into long strips of painting to strengthen the horizontal movement space produced by the horizontal visual effect. This 'Boundary Breaking Method' is sometimes more subtle, limited to the top of the character's head and the The subtle details of the soles of the feet superimpose the figures' heads and feet on the top and bottom borders of the picture, creating a feeling of going beyond the borders." The murals are arranged in left-to-right or right-to-left order. If the content is in the upper and lower rows, the lower row is from left to right, and the upper row is from right to left, and vice versa. This order not only makes the mural content look vivid, but also facilitates the painter's operation. This method is similar to the spelling rules of early Greek and is called "Boustrophedon" (Greek). ΒΟΥΣΤΡΟΦΗΔΟΝ For the overall silhouette, painters generally tend to use convex curves (Convex curves), combined with ochre color (Ochre), to express a strong reality. The pictorial features of Chiaroscuro and Without Shadows are prevalent in Sogdiana frescoes. This Greek-Sogdian pictorial character and artistic approach emerged in the centuries following the end of Hellenistic rule, and in itself reflects the far-reaching influence of Hellenism.[65]

The form appears in the Sogdian calendar and is used to denote the month of November[67]

------------------------------Studies by B. I. Marshak and F. Grene showed that the four-armed goddess, who plays the main role in the mural composition “Lamentation”, was correctly identified as Nana from the very beginning. At the same time, the Mesopotamian basis of the ritual depicted in the composition clearly manifested itself after studying the notes of Wei Jie and the Sogdian Manichaean fragment M 549. As can be judged from these written sources, the rite of mourning, which is known in the Near Asian myth of Tammuz, is led by “Lady Nana”. On the mural, Nana, along with other gods and people, mourns a girl who could be Geshtinanna (Belili), the sister of Tammuz, or Persephone, the daughter of Demeter. In Mesopotamian myth Geshtinanna replaces Tammuz every year for several months. In Sogd, the image of Geshtinanna could merge with the image of Persephone. According to N. Sims-Williams, the Greek name of Demeter in his Sogdian adaptation Zhimat is mentioned in the text M 549, and this theonym could have penetrated into Sogdian from the Bactrian language.

The Sogdian deity Takhsich was associated with Nana, whose name, according to the etymology proposed by K. Tremblay, means "Returning". Perhaps, as V. B. Henning suggested, Takhsich is the Sogdian hypostasis of Tammuz, who annually returns to earth. It is also possible that Takhsich is an epithet that replaces the main name of the deity. In Sogdian iconography, Nana has many companions, one of the most important being the deity with an arrow in his hand. This image reminiscent of a play on words in Middle Persian - mir - “arrow” and Tir (i) - the name of the Near Asian deity and the name of the planet Mercury, as well as the name of the deity, often identified with the Avestan Tishtriya, the genius of the star Sirius and the deity rain (Grenet, Marshak 1998, pp. 5–18). This interpretation once again showed the complexity of the tasks facing the researcher studying the ambiguous and multifaceted Sogdian paintings. B. I. Marshak solved such problems more than once with brilliance thanks to attention to detail, his erudition and the ability to see a well-known fact from a new perspective, which always led to unexpected discoveries in the history of culture. This was the essence of the researcher's method.[70]

Thus, from small pieces, combining the reconstructing of figures from small details, analogies and logical analysis he solved the “jigsaw-puzzle” of a painting in XXVI/3, the depiction of a festival with dancers, acrobats, masters of puppets, Dionysian mysteries and exposition of figures of gods.[72]

παράσταση του Μ. Αλεξάνδρου από το Fayaz Tepe

ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΤΙΚΗ ΕΠΙΡΡΟΗ ΣΤΗΝ ΠΕΡΙΟΧΗ ΠΕΡΙ ΤΟ TERMEZ (1-3 αι. μ.Χ.)[75]

Οι οικιστικές θέσεις του αρχαίου Termez κατέχουν μιαν εξέχουσα θέση στην ιστορία της αναπτύξεως του βουδιστικού πολιτισμού και της διαδόσεώς του στα ανατολικά. Με κάθε ανασκαφική περίοδο τόσο γνωστοί αρχαιολογικοί χώροι όπως το Kara Tepe, το Fayaz Tepe και το Zurmala εμπλουτίζουν το θησαυρό του βουδιστικού πολιτισμού με νέα αρχιτεκτονικά και καλλιτεχνικά προϊόντα. Για να κρίνουμε από το διαθέσιμο υλικό, η πιο εντατική περίοδος της βουδιστικής καλλιτεχνικής δραστηριότητας σε αυτόν τον τομέα συσχετίστηκε με την εποχή του Μεγάλου Κουσάν, από τον 1ο έως τον 3ο αιώνα. Εκτός από κέντρα λατρείας με μοναστήρια όπως το Kara Tepe και το Fayaz Tepe, που βρίσκονται έξω από τα τείχη της πόλης, υπήρχαν επίσης ναοί και ιερά μέσα στην πόλη. Αυτό είναι σαφές από την ανακάλυψη ενός μνημειακού κτηρίου εντός των ορίων της πόλης και των θραυσμάτων αρχιτεκτονικής διακόσμησης και μεμονωμένων γλυπτών βουδιστικού τύπου στον χώρο του Old Termez.

Διάζωμα από ασβεστολιθικό υλικό με παράσταση στεφανηφόρων (από το Dunye Tepe)[80]

Το παρόν άρθρο στοχεύει στην ανάλυση των έργων τέχνης - γλυπτά και ανάγλυφα - που βρέθηκαν σε παλαιότερες και πρόσφατες ανασκαφές στο Old Termez και στη γύρω περιοχή. Θα εξετάσει επίσης τα ευρήματα του παρελθόντος που δεν έχουν λάβει επαρκή συζήτηση σε προηγούμενες δημοσιεύσεις, παρά τη μεγάλη σημασία της έρευνας για τον βουδιστικό πολιτισμό των αρχαίων Termez.

Κύριος χαρακτήρας (αριστερα) και στεφανηφόρος (δεξιά)[82]

Το Βουδιστικό σύμβολο triratna: ένα βουδιστικό σύμβολο, που πιστεύεται ότι αντιπροσωπεύει οπτικά τα Τρία Κοσμήματα του Βουδισμού (ο Βούδας, το Ντάρμα, η Σάνγκα)[85]

ΘΕΑΤΡΙΚΑ ΔΡΩΜΕΝΑ ΣΤΟ ΙΕΡΟ ΤΟΥ PANJIKENT ΤΗΣ ΣΟΓΔΙΑΝΗΣ ΣΥΜΦΩΝΑ ΜΕ ΤΟ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΟ ΠΡΟΤΥΠΟ (THEATER PERFORMANCES & AUTOMATA PAINTED IN FRESCOES OF PENJIKENT TEMPLE - FOLLOWING THE GREEK PROTOTYPE - MODEL)[90]

Σύμφωνα με τον Marshak,[92] υπήρχε τεχνολογία στον ναό που επέτρεπε να ανυψωθεί η εικόνα ενός θεού. Υπήρχε και μια αίθουσα που πιθανώς είχε χρησιμοποιηθεί για την δημιουργία θεατρικών εφέ. Είναι πιθανόν τα τελετουργικά να είχαν θεατρικό χαρακτήρα, συμπεριλαμβανομένων των ειδικών εφέ, με τους Σογδιανούς να πραγματοποιούν πιθανώς θρησκευτικές/μυθολογικές σκηνές. Δύο τοιχογραφίες (που βρέθηκαν σε παρεκκλήσι και στην αυλή), που χρονολογούνται στον 6ο αιώνα, επιβεβαιώνουν την άσκηση της θεατρικής λατρείας. Όλα τα έργα στο ναό χρηματοδοτήθηκαν από ιδιώτες δωρητές. Στο ναό υπήρχε και φούρνος.

Αργίμπασα - Αφροδίτη σε τοιχογραφία του Penjikent Argimpasa - Aphrodite in Penjikent mural[93]

Οι πολυάριθμες εικόνες των θεών στους ναούς, καθώς και η Σογδιανή θρησκευτική ορολογία, υποδεικνύουν ότι οι ναοί θεωρούνταν από τους Σογδιανούς ως "τόπος - κατοικία των θεών, που θυμίζει την αντίστοιχη άποψη για τους Ελληνικούς: αναπαραστάσεις ιερών πομπών στους ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΟΥ ναούς, σύμφωνα με τον J. Harrison, ήταν 'προσευχές ή έπαινοι μεταφρασμένα σε πέτρα', υποδηλώνοντας ότι όλες οι σκηνές ήταν μέρος της τελετουργίας. Υλικό από την τέταρτη περίοδο του ιερού ΙΙ επιβεβαιώνουν ότι εικόνες από το Panjikent συμπεριελαμβάνοντο στις τελετουργίες.

Ο Marshak υποστήριξε ότι υπήρχε κάποια μηχανική συσκευή στο Panjikent που ύψωνε μιαν οθόνη ή εικόνα ενός θεού.[95] Ένα τελετουργικό που περιλάμβανε την χρήση μηχανημάτων θαυματουργών θυμίζει θεατρική παράσταση με στοιχεία της μυστηριακής ιεροτελεστίας,[98] στο κέντρο της την κινούμενη εικόνα μιας θεότητας. Ένα μυστικό δωμάτιο στο εσωτερικό μιας ράμπας τέταρτης περιόδου που ανέβαινε στην κορυφή της πλατφόρμας του Ιερού II θα μπορούσε επίσης να έχει χρησιμοποιήθεί για σκηνικά εφέ. Επεισόδια από την ζωή των θεών πιθανώς απαγγέλθηκαν ή παίχτηκαν κατά την διάρκεια της τελετουργίας, επιτρέποντας έτσι στο κοινό που παρακολουθεί την παράσταση να εμπλακεί σε αυτήν. Μιά τοιχογραφία του 6ου αι. από το βόρειο παρεκκλήσι στην αυλή του Ιερού II αντιπροσωπεύει αυτό το είδος θεατρικής τελετουργίας. Μπροστά σε μια θεά[100] καθισμένη σε ένα θρόνο σε σχήμα φανταστικού ζώου, παριστάνεται μια ομάδα ανθρώπων που παίζουν ρόλους διαφορετικών θεών. Μια ομάδα ανθρώπων που παρουσιάζονται ως μικρότεροι αντιπροσωπεύουν τους θνητούς.[105] Μάλιστα ένας άλλος πίνακας του έκτου αιώνα από βοηθητικό ιερό στο βόρειο τμήμα της αυλής του Ναού Ι (Αίθουσα 10a) αναπαριστά χορεύοντες ανθρώπους με μάσκες ζώων, οι οποίοι κρατούν μουσικά όργανα.[110]

ΑΡΧΙΤΕΚΤΟΝΙΚΗ ΣΥΣΧΕΤΙΣΗ

Γιά την αρχιτεκτονική των [τετράστυλων] ιερών του Penjikent και την Ελληνιστική συσχέτισή τους βλ.:

brill.com/aioo

Salaris, D. 2017.

Η μελέτη του Salaris παρέχει μια νέα προσέγγιση και ερμηνεία ενός απομακρυσμένου τετράστυλου ναού τhw Eλυμαίδος που βρέθηκε κατά την διάρκεια των ανασκαφών που διεξήχθησαν στις ιερές αναβαθμίδες του Bard-e Neshandeh στα μέσα του 19ου αιώνα. Σκαρφαλωμένο στα ύψη των βουνών Zagros στη σημερινή επαρχία Khuzestan ( ΝΔ Ιράν), το ιερό στο κάτω πεζούλι αντικατοπτρίζει μια καινοτόμο σύνθεση δομικών στοιχείων που εμπλέκουν τόσον Μεσοποταμία όσο και Ιρανικά πρότυπα και κατέχει μια ιδιαίτερη θέση στα αρχεία της αρχιτεκτονικής ναών του Ιρανικού κόσμου πριν από την κατάκτηση των Σασανιδών. Σύμφωνα με αυτή την έρευνα, προτείνεται μια επαναξιολόγηση του τετράστυλου ναού προκειμένου να αποφέρει νέες γνώσεις και πρόοδο κατανόησης σχετικά με τον λατρευτικό μνημειακό μηχανισμό στην Ελληνιστική και Παρθική Ελυμαϊδα.[120]

KAFIR-KALA ΤΑΤΖΙΚΙΣΤΑΝ: ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΤΙΚΕΣ ΕΠΙΡΡΟΕΣ

Penjikent & Ελλάς: Σύνοψη δανείων & συσχετίσεων

(1) Οι τετράστυλοι ναοί του Penjikent υιοθετούν την ελληνιστική τετραστυλική αρχιτεκτονική,

(2) τρίτωνες σε βάθρο Penjikent,

(3) ελληνιστικός και κινέζικος δράκος σε τοιχογραφίες,

(4) λεόντειες μορφές ελληνορωμαϊκής καταγωγής (π.χ. θεά σε λιοντάρι κ.λπ.),

(5) Αργιμπάσα-Αφροδίτη σε νωπογραφία,

(6) θεατρική λατρεία σε ναούς,

(7) αυτόματα/Deus ex machina στους ναούς των Πεντζικέντων & στην Ελλάδα

ΣΑΜΑΡΚΑΝΔΗ

Ο Τρίτων στο νερό

Η τοιχογραφία της Αίθουσας Πρεσβειών (Ambassador Ηall) του ανακτόρου στην Σαμαρκάνδη (Ουζμπεκιστάν), απεικονίζει αυλικές γυναίκες από την δυναστεία των Tang σε θαλάσσια διαδρομή με λέμβο διαθέτουσα κεφαλή γρύπα στην πλώρη. Στο νερό υπάρχει επίσης απεικόνιση του μικρού θεού της θάλασσας Τρίτωνα υπό την μορφή μειξογενούς θηρίου με "κεφάλι αλόγου και ουρά ψαριού" στο νερό, όπως επίσης και άλλα υδρόβια πλάσματα. Αφού οι Ρώσοι μελετητές αποκατέστησαν την τοιχογραφία, πίστεψαν ότι το άσχημο τέρας στο νερό κάτω από το μεγάλο πλοίο ήταν ένας «μεγάλος δράκος» με ανοιχτό στόμα και γλώσσα, ένας κινέζικος υβριδικός δράκος με φτερά και ένα πόδι κατσίκας, συμπέρασμα το οποίο ήταν λάνθασμένο αφού δεν εδόθη σημασία στην καλλιτεχνική επίδραση της εξελίξεως του ελληνιστικού θεού της θάλασσας στην Κεντρική Ασία. Στην πραγματικότητα, το πρώτο και το δεύτερο ανάγλυφο στους τοίχους του τάφου του Yu Hong της δυναστείας Sui στην Taiyuan παρέχουν ένα εντυπωσιακό σχέδιο ψαριού με κεφαλή αλόγου, το οποίο επίσης προέρχεται από την πλαστική τέχνη του μικρού θεού της θάλασσας Τρίτωνος.

ΣΗΜΕΙΩΣΕΙΣ

[2]. Encyclopaedia Iranica, s.v. Sogdiana iv. Sogdian Art.[2a]. Reck 2020, p. 2.

[3]. Shenkar 2017.[5]. Marshak and Raspopova 1994, p. 197.[5a1]. Ο Σογδιανός κιθαρωδός έχει συγκριθεί με τον θεό Απόλλωνα, αλλά είναι πολύ απίθανο ένας Έλληνας θεός να εμφανίζεται στα κεραμεικά στα οποία εμφανίζεται μια καθιστή μορφή να παίζει αυτό το όργανο. Οι Σογδιανοί μουσικοί είναι πολύ πιο κοντά στις πολλές αναπαραστάσεις στην Ύστερη Αρχαιότητα και την Πρώιμη Βυζαντινή τέχνη ενός καθιστού Ορφέως ο οποίος, ως Θρακιώτης, απεικονιζόταν από καλλιτέχνες ως βάρβαρος που φορούσε ενδύματα που μοιάζουν με εκείνα ενός Πάρθου ή των τοπικών ευγενών της Ρωμαϊκής Συρίας. [5a2]. Greek sophist of the Roman period Athens.[6]. Marshak and Raspopova 1994, p. 198.[7]. Marshak and Raspopova 1994, p. 202.[10]. Furniss, I. THE SOGDIANS.[15]. Mourning Scene. Panjikent, Tajikistan, south wall of main hall of Temple II, Wall painting, 6th c. CE, The State Hermitage Museum, SA-16236.[17]. pl. 6 in p. 156 of: V. G. Skoda (St. Petersburg)[20]. de la Vaissière 2003.[21]. Bellemare and Lerner.[22]. Azarnoush and Grenet 2007.[30]. Encyclopaedia Iranica, s.v. PERSONAL NAMES, SOGDIAN i. IN CHINESE SOURCES.[32]. Terracotta group of two seated women, perhaps Demeter and her daughter Persephone. Made at Myrina, north-west Asia-Minor (????), circa 180 BCE. Said to be from Asia-Minor. (The British Museum 1885,0316.1).

[40]. ICOSMOS. Spring 2021.[45]. Grenet 2013.

[50]. The Ohio State University.

[55]. Sanping Chen 2019, p. 423.

[60]. Grenet and Marshak 1998.

[62]. Compareti 2012. Κάτω εικόνα: Illustrated folio from Kalila wa Dimna, 13th century. Ink and color on paper. H. 30 × W. 23 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS Arabe 3467, Folio 22r.

[65]. Qi Xiaoyan 2022.[67]. Qi Xiaoyan 2022.

[70]. Shkoda 2013, pp. 156-157.

[72]. Shkoda 2013, pp. 484.

[75]. Abdullaev 2013.

[80]. https://scontent.fskg1-1.fna.fbcdn.net/v/t1.6435-9/140834319_296218728818024_6129775284491566833_n.jpg?_nc_cat=109&ccb=1-7&_nc_sid=730e14&_nc_ohc=JfE4RHbe0DsAX-dUGah&_nc_ht=scontent.fskg1-1.fna&oh=00_AT_KxZjpnE1bBMSBdiHQnnvPH9SLvCnchiXIVTvVzIGRvQ&oe=63470582

[82]. https://scontent.fskg1-1.fna.fbcdn.net/v/t1.6435-9/141019225_296219322151298_8947146624964246467_n.jpg?_nc_cat=103&ccb=1-7&_nc_sid=730e14&_nc_ohc=StuslYL41YQAX-kvUwQ&_nc_ht=scontent.fskg1-1.fna&oh=00_AT_AsQxFpxV208EYyEYAqtvs0EpJGuQ5ICehbt_SYCJPVg&oe=6349B43A

[85]. https://scontent.fskg1-1.fna.fbcdn.net/v/t1.6435-9/141039892_296220048817892_7229518744817041116_n.jpg?_nc_cat=102&ccb=1-7&_nc_sid=730e14&_nc_ohc=Cu8Cte1bFbcAX_YVqrt&tn=VJdYNA9Ryva7mb0-&_nc_ht=scontent.fskg1-1.fna&oh=00_AT_r4sH8ncKG-MxV0oyaWkVDaNU6seqUoKKgpbTD9J0AXw&oe=6346FE32

[90]. Shkoda 1996.

[92]. WIKI, s.v. Sogdian Art; Marshak and Raspopova 1994.

[93]. https://scontent.fskg1-1.fna.fbcdn.net/v/t39.30808-6/273421790_542588177514410_7077360845891430604_n.jpg?_nc_cat=102&ccb=1-7&_nc_sid=dbeb18&_nc_ohc=pAyENIUnfbAAX9XMfXi&_nc_ht=scontent.fskg1-1.fna&oh=00_AT-blSFaHpftqPba5c00J_NzBlZeFfuNUEq2WV9D086Rug&oe=63287A90

[95]. Shkoda 1996, n. 40.

[98]. Shkoda 1996, n. 41. Αξίζει να αναφέρουμε ότι οι αρχαίοι ΕΛΛΗΝΕΣ θεωρούσαν τις θεατρικές παραστάσεις ως μέρος της κρατικής λατρείας.

[100]. Pιθανώς την Αργίμπασα - Αφροδίτη!

[105]. Shkoda 1996, n. 43. Για τη λεπτομερή περιγραφή της και την επιχειρηματολογία βλ. Marshak and Raspopova (Marshak and Raspopova 1994).[110]. Shkoda 1996, n. 44.[120]. Salaris 2017.

[50]. The Ohio State University.

[55]. Sanping Chen 2019, p. 423.

[60]. Grenet and Marshak 1998.

[62]. Compareti 2012. Κάτω εικόνα: Illustrated folio from Kalila wa Dimna, 13th century. Ink and color on paper. H. 30 × W. 23 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS Arabe 3467, Folio 22r.

[65]. Qi Xiaoyan 2022.[67]. Qi Xiaoyan 2022.

[70]. Shkoda 2013, pp. 156-157.

ΒΙΒΛΙΟΓΡΑΦΙΑ

https://www.jstor.org/stable/24048774

Marshak, B. I. and V. I. Raspopova. 1994. "Worshipers from the Northern Shrine of Temple II, Panjikent," Bulletin of the Asia Institute (New Series) 8 (The Archaeology and Art of Central Asia Studies From the Former Soviet Union), pp. 187-207.

https://sogdians.si.edu/sidebars/retracing-the-sounds-of-sogdiana-sogdian-music-and-musical-instruments-in-central-asia-and-china/?fbclid=IwAR3vp0Pal8xm5OnBXJ8TifJZwBjFo2KMUDzrKjkVroEpazs4Y_7DGdQIOkM

Freer|Sackler

Furniss, I. THE SOGDIANS Influencers on the Silk Roads. RETRACING THE SOUNDS OF SOGDIANA. Online exhibition by the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

https://dnkonidaris.blogspot.com/2022/03/dionysus-heracles-as-character-of.html

https://www.academia.edu/35720137/Divine_and_Human_Figures_on_the_Sealings_Unearthed_from_Kafir_kala_Japan_Society_for_Hellenistic_Islam_Archaeological_Studies_24_203_212_2017_in_Japanese_%E3%82%AB%E3%83%95%E3%82%A3%E3%83%AB_%E3%82%AB%E3%83%A9%E9%81%BA%E8%B7%A1%E5%87%BA%E5%9C%9F%E5%B0%81%E6%B3%A5%E3%81%AB%E8%A6%8B%E3%82%89%E3%82%8C%E3%82%8B%E7%A5%9E%E3%80%85%E3%81%A8%E4%BA%BA%E7%89%A9%E3%81%AE%E5%9B%B3%E5%83%8F_%E3%81%B8%E3%83%AC%E3%83%8B%E3%82%BA%E3%83%A0_%E3%82%A4%E3%82%B9%E3%83%A9%E3%83%BC%E3%83%A0%E8%80%83%E5%8F%A4%E5%AD%A6%E7%A0%94%E7%A9%B6_24_203_212_

Begmatov, A. 2017. "Divine and Human Figures on the Sealings Unearthed from Kafir-kala," Japan Society for Hellenistic-Islam Archaeological Studies 24, pp. 203-212.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/24048351

Litvinski, B., and V. Solov'ev. 1990. "The Architecture and Art of Kafyr Kala (Early Medieval Tokharistan)," Bulletin of the Asia Institute 4 (In honor of Richard Nelson Frye: Aspects of Iranian Culture), pp. 61-75. p. 61:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/24048767

Shishkina, G. V. 1994. "Ancient Samarkand: Capital of Soghd," Bulletin of the Asia Institute, New Series 8 (The Archaeology and Art of Central Asia Studies From the Former Soviet Union), pp. 81-99.

https://www.academia.edu/36102643/_The_Religion_and_the_Pantheon_of_the_Sogdians_5th_8th_centuries_CE_in_Light_of_their_Sociopolitical_Structures_Journal_Asiatique_2017_2_pp_191_209

Shenkar, M. 2017. "The Religion and the Pantheon of the Sogdiands (5th–8th centuries CE) in Light of their Sociopolitical Structures,” Journal Asiatique 2017/2, pp. 191-209.

https://archive.org/details/legendstalesfablesintheartofsogdianaborismarshak_678_G/mode/2up?view=theater

Marshak, B. 2002. Legends, Tales, and Fables in the Art of Sogdiana, New York.

https://www.academia.edu/23521408/%D0%AD%D0%A0%D0%9C%D0%98%D0%A2%D0%90%D0%96?auto=download&email_work_card=download-paper

Transactions of the State Hermitage Museum LXII. Sogdians, their precursors, contemporaries and heirs, Based on proceedings of conference “Sogdians at Home and Abroad”held in memoryof Boris Il’ich Marshak (1933–2006), St. Petersburg The State Hermitage Publishers 2013

https://www.jstor.org/stable/24048897

Marshahk, B. I. 1996. "The Tiger, Raised from the Dead: Two Murals from Panjikent," Bulletin of the Asia Institute, New Series 10 (Studies in Honor of Vladimir A. Livshits), pp. 207-217.

Shkoda, V. G. 1996. "Fifty Years of Archaeological Exploration in Panjikent," Bulletin of the Asia Institute, New Series 10 (Studies in Honor of Vladimir A. Livshits), pp. 259-264.

https://www.persee.fr/doc/arasi_0004-3958_1998_num_53_1_1413

Grenet, F. and B. Marshak. 1998. "Le mythe de Nana dans l'art de la Sogdiane," Arts Asiatiques 53, pp. 5-18.

http://www.silkroadfoundation.org/newsletter/srjournal_v1n2.pdf

de la Vaissière, E. 2003. "Sogdians in China," The Silk Road 1 (2), pp. 23-27.

ICOSMOS. Spring 2021. Serial Transnational Nomination For World Heritage of Silk Roads, <http://www.iicc.org.cn/UserFiles/Article/file/6377094899523997951113530.pdf>

https://www.academia.edu/24470615/Where_are_the_Sogdian_Magi_

https://www.jstor.org/stable/24049370

Azarnoush, S., and F. Grenet. 2007. "Where Are the Sogdian Magi?," Bulletin of the Asia Institute (New Series) 21, pp. 159-177.

Grenet, F. 2013. "Refocusing Central Asia. Inaugural Lecture delivered on Thursday 7 November 2013. <https://books.openedition.org/cdf/4297>

The Ohio State University. "An Introduction to Uzbekistan," The Ohio State University, <https://u.osu.edu/uzbekistan/history/part-one-antiquity-silk-roads-and-world-religions/?fbclid=IwAR0MbGldYCbtOo3zh38da8vDsW04ouRmKl_WQgTfwVZnmZiBYYPy_akiR58> (11 Sept. 2022).

https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7817/jameroriesoci.139.2.0417

Sanping Chen. 2019. “'Godly Worm' and the 'Literati Prism' of Chinese Sources," Journal of the American Oriental Society 139.2, pp. 417-431.

https://www.academia.edu/23521408/%D0%AD%D0%A0%D0%9C%D0%98%D0%A2%D0%90%D0%96?auto=download&email_work_card=download-paper&fbclid=IwAR3pfGu3j36xAV7SKLqOlOHu2GlR6bReS9vTOc0Ga2r0sZ7yCydMY4kbkjY

Shkoda, V. G. 2013. "Boris Marshak and Panjikent Painting (Researcher's Method)," in Sogdians, their precursors, contemporaries and heirs , St. Petersburg (The State Hermitage Publishers), pp. 147-158.

https://www.academia.edu/24461082/Le_mythe_de_Nana_dans_lart_de_la_Sogdiane

Grenet, F. and B. Marshak. 1998. "Le mythe de Nana dans l'art de la Sogdiane," Arts Asiatiques 53, pp. 5-18.

https://inf.news/en/travel/98715065977fc276c11815d02be58968.html?fbclid=IwAR1_dFhd0gLCAuulyS3t9UwsEYgPNwK3f8Yd94hdsvWYkdbuobneD-xIUAE

Qi Xiaoyan. 2022. "Frontier Time and Space, The introduction and continuation of Hellenistic culture in the ancient city of Sogdiana," <https://inf.news/en/travel/98715065977fc276c11815d02be58968.html?fbclid=IwAR1_dFhd0gLCAuulyS3t9UwsEYgPNwK3f8Yd94hdsvWYkdbuobneD-xIUAE> (11 Sept. 2022).

Bellemare, J. and J. A. Lerner. "The Sogdians at home. Art and Material Culture," <https://sogdians.si.edu/the-sogdians-at-home/> (11 Sept. 2022).

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313615908_The_Buddhist_culture_of_ancient_Termez_in_old_recent_finds

Abdullaev, K. 2013. "The Budhist culture of ancient Termez in old and recent finds," Parthica 15, Pisa / Roma, pp. 157-188.

https://www.academia.edu/1809993/Classical_Elements_in_Sogdian_Art?fbclid=IwAR30ImAuhMUBapZPEC2G_7Y1CflFcVEHlxnULrLt2-7AhidTkeWPbkvhW18

Compareti, M. 2012. "Classical Elements in Sogdian Art," Iranica Antiqua XLVII, pp. 303-316.

https://brill.com/view/journals/aioo/77/1-2/article-p134_6.xml?language=en

https://brill.com/downloadpdf/journals/aioo/77/1-2/article-p134_6.pdf

Salaris, D. 2017. "A Case of Religious Architecture in Elymais: The Tetrastyle Temple of Bard-e Neshandeh," Annali, Sezione orientale 77, pp. 134–180.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/24048896?read-now=1&seq=7#page_scan_tab_contents

Shkoda, V. G. 1996. "The Sogdian Temple: Structure and Rituals," Bulletin of the Asia Institute (New Series) 10 (Studies in Honor of Vladimir A. Livshits), pp. 195-206.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/24048774#metadata_info_tab_contents

Marshak, B. I, and V. Raspopova. 1994. "Worshippers from the Northern Shrine of Temple II, Panjikent," Bulletin of the Asia Institute 8. pp. 187-207.

https://www.academia.edu/35720137/Divine_and_Human_Figures_on_the_Sealings_Unearthed_from_Kafir_kala_Japan_Society_for_Hellenistic_Islam_Archaeological_Studies_24_203_212_2017_in_Japanese_%E3%82%AB%E3%83%95%E3%82%A3%E3%83%AB_%E3%82%AB%E3%83%A9%E9%81%BA%E8%B7%A1%E5%87%BA%E5%9C%9F%E5%B0%81%E6%B3%A5%E3%81%AB%E8%A6%8B%E3%82%89%E3%82%8C%E3%82%8B%E7%A5%9E%E3%80%85%E3%81%A8%E4%BA%BA%E7%89%A9%E3%81%AE%E5%9B%B3%E5%83%8F_%E3%81%B8%E3%83%AC%E3%83%8B%E3%82%BA%E3%83%A0_%E3%82%A4%E3%82%B9%E3%83%A9%E3%83%BC%E3%83%A0%E8%80%83%E5%8F%A4%E5%AD%A6%E7%A0%94%E7%A9%B6_24_203_212_

Begmatov, A. 2017. "Divine and Human Figures on the Sealings Unearthed from Kafir-kala", Japan Society for Hellenistic-Islam Archaeological Studies 24, pp. 203-212.

http://www.silkroadfoundation.org/newsletter/december/archaeology.htm?fbclid=IwAR3P0lwz0B1yw6k5k6aE7shdsSO0y6roBERJFPomGUiIXVVtYj6vLoQJIjU

Marshak, B. I. 2003. "The Archaeology of Sogdiana," The Silk Road Newsletter 1 (2), <http://www.silkroadfoundation.org/newsletter/december/archaeology.htm?fbclid=IwAR3P0lwz0B1yw6k5k6aE7shdsSO0y6roBERJFPomGUiIXVVtYj6vLoQJIjU>

Litvinski, B., and V. Solov'ev. 1990. "The Architecture and Art of Kafyr Kala (Early Medieval Tokharistan)," Bulletin of the Asia Institute 4 (In honor of Richard Nelson Frye: Aspects of Iranian Culture), pp. 61-75.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/24048767

Shishkina, G. V. 1994. "Ancient Samarkand: Capital of Soghd," Bulletin of the Asia Institute, New Series 8 (The Archaeology and Art of Central Asia Studies From the Former Soviet Union), pp. 81-99.

https://www.academia.edu/36102643/_The_Religion_and_the_Pantheon_of_the_Sogdians_5th_8th_centuries_CE_in_Light_of_their_Sociopolitical_Structures_Journal_Asiatique_2017_2_pp_191_209?email_work_card=title

Michael Shenkar. 2017. "The Religion and the Pantheon of the Sogdians (5th–8th centuries CE) in Light of their Sociopolitical Structures," Journal Asiatique 2017/2, pp. 191-209.

https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=pfbid0btKb7spPtX8Bvy76itbPqFUZgRLoYBYZUz4oaNnxHnKpBRiJMYiFktv1HqV5Ck5El&id=100052896971032&__cft__[0]=AZVMF9ZISp2OsK1Kj406JbXP3k9orI3xGuX9q9iflai1Bu04M0JhE9zPuTfL04WPtkKkfQqmqqGn-0lFud71MPT5078c5T3Vjloel776JRiecObb46bjWer4RWNZr6ouXolcHkpXncM2N-d2Dj1guVJu3C_q68fHcADtVcUhUU0Xyw&__tn__=%2CO%2CP-R

΄

https://www.laitimes.com/en/article/60qta_6h5de.html?fbclid=IwAR29lrcCy0KAslmX_FWa-Dn2LLX7QXMDh629j6FsJ86E3M8CevQUeY9k0Jw#google_vignette

Ge Chengyong. 2023. "Από το Αιγαίο μέχρι το Τσαγκάν της δυναστείας των Tang. Έρευνα για το πρόσφατα ανακαλυφθέν τρίχρωμο κερατόσχημο κύπελλο Tang Sancai με παράσταση Τρίτωνος," (从 爱 琴 海 刨 唐 长 安 一 新 发 现 唐 三 彩 帐 腔 海 神 特 里 同 造 型 角 杯 研 究 ) Cultural Relics Press <https://www.wenwu.com/newsinfo/6365824.html> (19 Nov. 2023).

https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=pfbid0A9FR28rw8p8fFpvXo7z8k1qKLPT54igThmZWjNf6xuRQCjfafWU9rGb6ThS6V8Wsl&id=100052896971032&__cft__[0]=AZWMxaF3Bw789jORRYiBb_OQqZpVY7PzKT3XVbTZf0_9YR6b6wGNhE16e5ZQXk5lrQvNwkVbufUIfPhYCX0PoSsvt4wvFYjBG__1rq1ZebCjVSyTWfqKB5Dro1OuhHO4DFl7GtrPt920dZSR0JStqjOYtzzdWXEfoae5wDAjSsDlew&__cft__[1]=AZWMxaF3Bw789jORRYiBb_OQqZpVY7PzKT3XVbTZf0_9YR6b6wGNhE16e5ZQXk5lrQvNwkVbufUIfPhYCX0PoSsvt4wvFYjBG__1rq1ZebCjVSyTWfqKB5Dro1OuhHO4DFl7GtrPt920dZSR0JStqjOYtzzdWXEfoae5wDAjSsDlew&__tn__=%2CO%2CP-R]-R

Η ΔΙΑΔΟΣΗ ΤΗΣ ΕΙΚΟΝΟΓΡΑΦΙΑΣ ΤΟΥ ΤΡΙΤΩΝΟΣ ΣΤΗΝ ΚΙΝΑ ΚΑΙ ΕΝ ΓΕΝΕΙ ΤΗΝ ΑΣΙΑ

https://www.semanticscholar.org/reader/7d93ce010c25439d799fc3aa26fc725921e0bb13

Reck, C. 2020. “The Sogdians and Their Religions in Turfan: Evidence in the Catalogue of the Middle Iranian Fragments in Sogdian Script of the Berlin Turfan Collection,” Entangled Religions 11.6, pp. 1-18.

CLASSICAL ELEMENTS IN SOGDIAN ART: AESOP’S FABLES REPRESENTED IN THE MURAL PAINTINGS AT PENJIKENT (Matteo COMPARETI) Aratus the Poet and Urania the Muse of Astronomy, c.1800 After Henry Fuseli RA (1741 - 1825) ---->

Fig. 26. Painting from Panjikent, Room 1/XXI, “The Goose (Duck) with the Golden Eggs,” first quarter of the 8th century c.e. After Marshak 2002: fig. 86.

https://hal.science/hal-03334673v1/file/18-Dan-BAI_30.pdf

Anca Dan and Frantz Grenet. 2020-2021. "Alexander the Great in the Hephthalite Empire: “Bactrian” Vases, the Jewish Alexander Romance, and the Invention of Paradise," Bulletin of the Asia Institute (New Series) Volume 30, pp. 143-194.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283346297_Classical_elements_in_Sogdian_art_Aesop%27s_fables_represented_in_the_mural_paintings_at_Penjikent/figures?lo=1

ΠΛΕΟΝ ΠΡΟΣΦΑΤΟΣ ΕΜΠΛΟΥΤΙΣΜΟΣ - ΕΠΙΜΕΛΕΙΑ: 030724

DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.17477.15842

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/392562915_ELLENIKES_EPIRROES_STEN_SOGDIANE

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου