FAR FASCIST BEHAVIOUR FROM LYN GREEN AND FACEBOOK GROUP 'FAYUM PORTAITS'!

POST - containing only quotes from established researchers - which was deleted by the fascist group FAYUM PORTRAITS with the help of the pseudo - 'scientist' Lyn Green (ROYAL ONTARIO MUSEUM).ΑΝΑΡΤΗΣΗ - περιέχουσα μόνον αποσπάσματα καταξιωμένων ερευνητών - ένεκα της οποίας διεγράφην από την φασιστικών αντιλήψεων ομάδα FAYUM PORTRAITS τη βοηθεία και της 'επιστημόνισσας' Lyn Green (ROYAL ONTARIO MUSEUM).

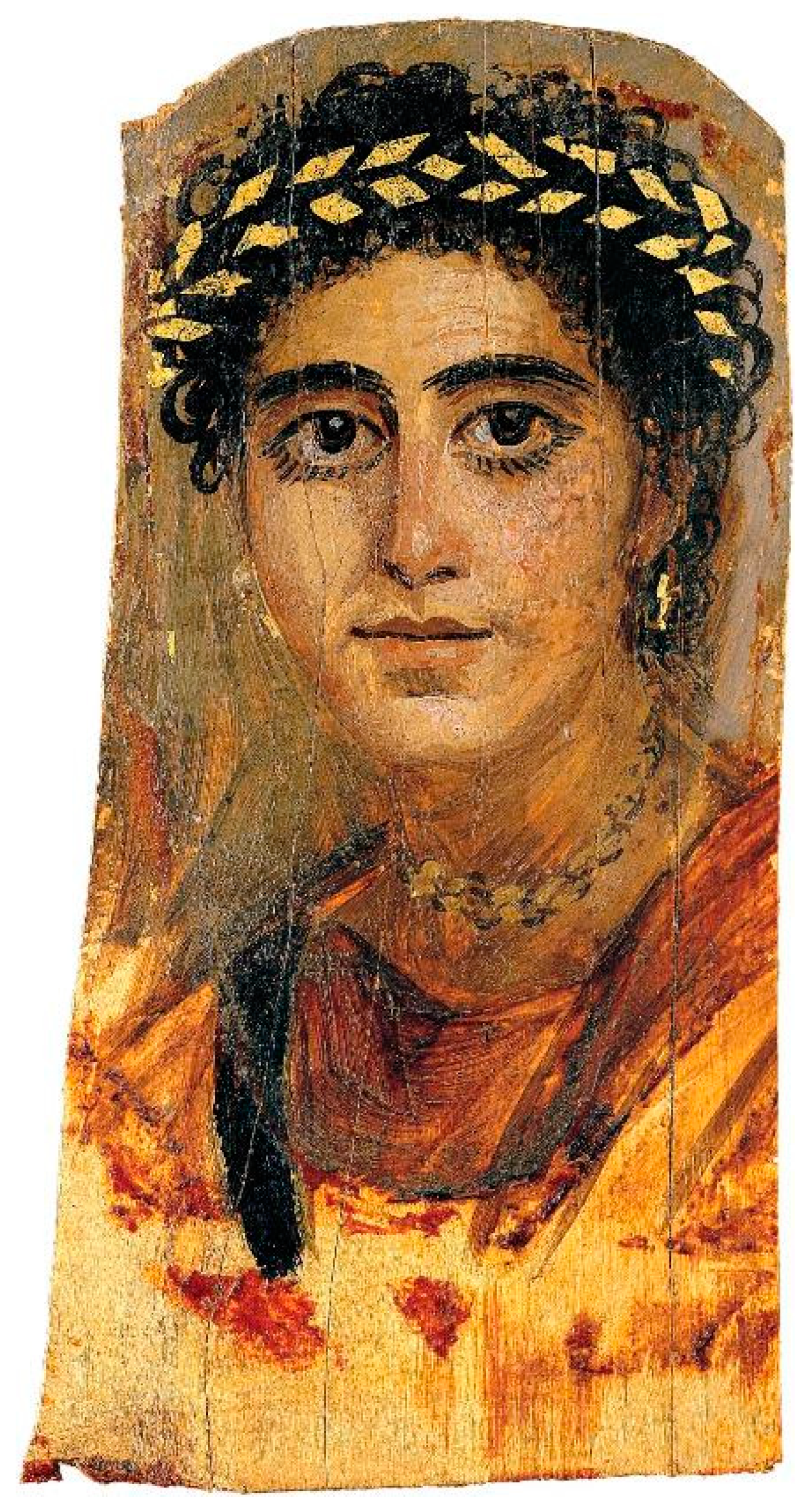

painting and gold leaf on wooden panel; perhaps from Hawara (Fayum), Egypt; ca. 50–100 ce [Photography by Michiel Bootsman; courtesy of the Allard Pierson Museum]

The girl’s portrait offers the visitors a fascinating glimpse not only of the blending of Greek, Roman and Egyptian funerary practices and beliefs, but also the entanglements of Greek, Roman and Egyptian religious, cultural and artistic traditions. The panel portrait was originally inserted into the wrappings of the girl’s mummified remains. Mummification, to be sure, was an age-old Egyptian funerary practice dating back to the Early Dynastic Period (mid 3rd mill. bce [sometimes using Chios pistachio!]). This treatment of the deceased was believed to be necessary to preserve the body for the person’s spiritual entities beyond death, so that the individual could live on in the afterworld. The golden wreath in the girl’s short hair symbolizes her good fortune and divine protection in the afterlife after passing through the judgment before Osiris. During that Judgment, the dead’s heart is weighed against the feather of Ma’at. Should they fail the judgement, a monstrous being, called Ammit, would devour the dead. ....................................

Some of the wealthiest tombs show that GREEKS [Macedonians included] could also adorn their dead with golden wreaths even before the HELLENISTIC period, and this practice may be related to the mystery cults. In Hellenistic and Roman Egypt, these various funerary and religious traditions merged through the adoption and adaptation of different practices and beliefs.

......................................

The ENCAUSTIC painting technique was first developed in Classical Greece. The decoration of mummies with a panel portrait or one painted on linen was an invention of the Roman period. [NO THIS IS NOT TRUE:] (During the Hellenistic and Roman Imperial period, a more naturalistic stucco mask could be inserted into the mummy). It may be speculated that the invention was somehow related to the Roman conquest. Exactly why painted portraits were suddenly added to the mummified body of the deceased, however, remains uncertain. During her keynote address .. Susan Walker pointed out that the linden wood on which many Fayum portraits were painted generally derives from SE Europe, thus including the heartland of the MACEDONIAN veterans who settled in Egypt in the Hellenistic period. SOURCE: with minor mods & insertions [], "The Girl with the Golden Wreath: Four Perspectives on a Mummy Portrait", Judith Barr, Clara M. ten Berge, Jan M. van Daal and Branko F. van Oppen de Ruiter, mdpi

Egypt’s millennia-long tradition of accompanying the dead with protective gods is an international hallmark of iconography. Lifelike portraits combined with Egyptian imagery and symbols of the afterlife seem an incongruous juxtaposition but are characteristic during the first three-four centuries C.E., when funerary shrouds painted with traditional flat Egyptian registers of gods enacting rejuvenation rites accompanied lifelike portraits of the dead painted according to the Greek tradition (Riggs 2005:98, figure 39). Where in several centuries there will be a mixture of pagan and Christian symbolism, at this time thereis a combination of Greek, Roman, and Egyptian style and iconography that could have made possible the assembly of a triptych or shrine to the memory of a departed Roman who placed religious value in the powerful protection of Isis and Serapis (Rondot 2013:262 [quoting Lorelei Corcoran]). In the portraits of the gods, linearity is replaced by modulation and two-dimensionality by the use of a variety of hues to achieve a three-dimensional portrayal. With their reference to future iconic imagery, it can be seen that representing Egyptian gods in Hellenistic Greek form pointed toward traditional imagery associated with the icon.

Pagan icons such as Isis and Serapis provide a historical context for that practice of worship, which in this format comingled with the cult of the dead and bound the living to the deceased in piety.

It is only a step to consider the origin of icon painting in this context, and scholars have seen that the religious phenomenon of venerating the icon started in the home, and in Egypt, where Mary first received the epithet Theotokos, a title once reserved for Isis (Mathews 2005:47). SOURCE: Hart, M. L. 2016. “A Portrait of a Bearded Man Flanked by Isis and Serapis,” in Icon, Cult, and Context: Sacred Spaces and Objects in the Classical World, ed. M. K. Heyn, A. I. Steinsapir, Ann I, Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, pp. 79-89.

BRITISH MUSEUM EA68509, Christina Riggs. The Beautiful Burial in Roman Egypt: Art, Identity, and Funerary Religion, pl. 6

Τα ολόσωμα σάβανα με φυσιοκρατικούς ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΟΥΣ πίνακες του εκλιπόντος συνιστούν μοναδικές επιβιώσεις από την Ρωμαϊκή Αίγυπτο. Σε αυτό το παράδειγμα, μια γυναίκα με ροζ χιτώνα και μανδύα κρατά νεκρικές προσφορές με οίνο και άνθη. Το πλαίσιο με ημιπολύτιμους λίθους σε τοξωτή διευθέτηση πάνω από την κεφαλή της πηγάζει από τις στήλες των αιγυπτιακών σκηνών δίπλα της. Ζωγραφισμένο λινό, β' μισό 2ου αι.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Full length shroud with naturalistic GREEK paintings of the deceased are unique survivals from Roman Egypt. In this example a woman in pink tunic and mantle holds funerary offerings of wine and flowers. The jewelled frame arched over her head springs from the columns of Egyptian scenes beside her. Painted linen, 2nd half of the 2nd c. BRITISH MUSEUM EA68509, Christina Riggs. The Beautiful Burial in Roman Egypt: Art, Identity, and Funerary Religion, pl. 6

Η προσωπογραφία της νεανίδας προσφέρει στους επισκέπτες μια συναρπαστική ματιά όχι μόνο στον συνδυασμό ελληνικών, ρωμαϊκών και αιγυπτιακών ταφικών πρακτικών και πεποιθήσεων, αλλά και στις εμπλοκές των ελληνικών, ρωμαϊκών και αιγυπτιακών θρησκευτικών, πολιτιστικών και καλλιτεχνικών παραδόσεων. Η προσωπογραφία επί πίνακος αρχικά εισήχθη στα περιτυλίγματα των μουμιοποιημένων λειψάνων του κοριτσιού. Η μουμιοποίηση, βέβαια, ήταν μια αρχαία αιγυπτιακή ταφική πρακτική που χρονολογείται από την Πρώιμη Δυναστική Περίοδο (μέσα 3ης χιλιετίας π.Χ. [μερικές φορές μάλιστα προς τούτο χρησιμοποιήθηκε μαστίχα Χίου!]). Αυτή η μεταχείριση του νεκρού πιστεύεται ότι ήταν απαραίτητη για τη διατήρηση του σώματος για τις πνευματικές οντότητες του ατόμου μετά θάνατον, ώστε το άτομο να μπορεί να συνεχίσει να ζει στον μετά θάνατον κόσμο. Το χρυσό στεφάνι στα κοντά μαλλιά του κοριτσιού συμβολίζει την καλή τύχη και τη θεϊκή προστασία της στη μετά θάνατον ζωή μετά την κρίση ενώπιον του Όσιρι. Κατά τη διάρκεια αυτής της Κρίσεως, η καρδιά του νεκρού ζυγίζεται έναντι του φτερού της Μάατ. Σε περίπτωση που αποτύχει στην κρίση, ένα τερατώδες ον, που ονομάζεται Αμμίτ, θα καταβρόχθιζε τον νεκρό. ------------------

Μερικοί από τους πλουσιότερους τάφους δείχνουν ότι οι Έλληνες [συμπεριλαμβα-νομένων των Μακεδόνων] μπορούσαν επίσης να στολίσουν τους νεκρούς τους με χρυσά στεφάνια ακόμη και πριν από την ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΤΙΚΗ περίοδο, και αυτή η πρακτική μπορεί να σχετίζεται με τις μυστηριακές λατρείες. Στην Ελληνιστική και Ρωμαϊκή Αίγυπτο, αυτές οι διάφορες ταφικές και θρησκευτικές παραδόσεις συγχωνεύτηκαν μέσω της υιοθέτησης και προσαρμογής διαφορετικών πρακτικών και πεποιθήσεων.

......................................

Η τεχνική της εγκαυστικής ζωγραφικής αναπτύχθηκε για πρώτη φορά στην Κλασική Ελλάδα. Η διακόσμηση της μούμιας με μία προσωπογραφία επί πίνακος ή ζωγραφισμένης σε λινό απετέλεσε μια εφεύρεση της Ρωμαϊκής περιόδου. [ΟΧΙ ΑΥΤΟ ΔΕΝ ΙΣΧΥΕΙ:] (Κατά την Ελληνιστική και Ρωμαϊκή Αυτοκρατορική περίοδο, μια πιο φυσιοκρατική μάσκα από γυψομάρμαρο μπορούσε να τοποθετηθεί στην μούμια). Μπορεί να υποτεθεί ότι η εφεύρεση σχετιζόταν με κάποιο τρόπο με την Ρωμαϊκή κατάκτηση. Ωστόσο, παραμένει αβέβαιο γιατί τα ζωγραφισμένα πορτρέτα προστέθηκαν ξαφνικά στο μουμιοποιημένο σώμα του νεκρού. Κατά τη διάρκεια της κεντρικής της ομιλίας... η Σούζαν Γουόκερ επεσήμανε ότι το ξύλο φλαμουριάς στο οποίο ζωγραφίστηκαν πολλά πορτρέτα Φαγιούμ προέρχεται γενικά από την ΝΑ Ευρώπη, συμπεριλαμβανομένης έτσι του τόπου προελεύσεως των ΜΑΚΕΔΟΝΩΝ βετεράνων που εγκαταστάθηκαν στην Αίγυπτο κατά την Ελληνιστική περίοδο. ΠΗΓΗ: με μικρές τροποποιήσεις και προσθήκες [], "Το Κορίτσι με το Χρυσό Στεφάνι: Τέσσερις Προοπτικές σε ένα Πορτρέτο Μούμιας", Judith Barr, Clara M. ten Berge, Jan M. van Daal και Branko F. van Oppen de Ruiter, mdpi

Η παράδοση χιλιετιών της Αιγύπτου να συνοδεύει τους νεκρούς με προστατευτικούς θεούς αποτελεί διεθνές σήμα κατατεθέν της εικονογραφίας. Τα ρεαλιστικά πορτρέτα σε συνδυασμό με αιγυπτιακές εικόνες και σύμβολα της μετά θάνατον ζωής φαίνονται μια αταίριαστη αντιπαράθεση, αλλά είναι χαρακτηριστικά κατά τους πρώτους τρεις-τέσσερις αιώνες μ.Χ., όταν τα ταφικά σάβανα ζωγραφισμένα με παραδοσιακές επίπεδες αιγυπτιακές μητρώα θεών που ενσάρκωναν τελετές αναζωογόνησης συνόδευαν ρεαλιστικά πορτρέτα των νεκρών ζωγραφισμένα σύμφωνα με την ελληνική παράδοση (Riggs 2005:98, εικόνα 39). Ενώ σε αρκετούς αιώνες θα υπάρχει ένα μείγμα παγανιστικού και χριστιανικού συμβολισμού, αυτή την εποχή υπάρχει ένας συνδυασμός ελληνικού, ρωμαϊκού και αιγυπτιακού στυλ και εικονογραφίας που θα μπορούσε να καταστήσει δυνατή τη συναρμολόγηση ενός τρίπτυχου ή ιερού στη μνήμη ενός εκλιπόντος Ρωμαίου που απέδιδε θρησκευτική αξία στην ισχυρή προστασία της Ίσιδας και του Σέραπι (Rondot 2013:262 [παραθέτοντας την Lorelei Corcoran]). Στα πορτρέτα των θεών, η γραμμικότητα αντικαθίσταται από τη διαμόρφωση και τη δισδιάστατη φύση με τη χρήση μιας ποικιλίας αποχρώσεων για την επίτευξη μιας τρισδιάστατης απεικόνισης. Με την αναφορά τους σε μελλοντικές εικονικές εικόνες, μπορεί να φανεί ότι η απεικόνιση αιγυπτιακών θεών σε ελληνιστική ελληνική μορφή υποδείκνυε την παραδοσιακή εικονογραφία που σχετίζεται με την εικόνα.

52 λ.

Απάντηση

Τροποποιήθηκε

Leonidas Analyths

Παγανιστικές εικόνες όπως της Ίσιδος και του Σεράπιος παρέχουν ένα ιστορικό πλαίσιο για αυτήν την πρακτική λατρείας, η οποία σε αυτή τη μορφή συνδυαζόταν με την λατρεία των νεκρών και συνέδεε τους ζωντανούς με τους νεκρούς με ευσέβεια. Είναι μόνο ένα βήμα για να εξετάσουμε την προέλευση της αγιογραφίας σε αυτό το πλαίσιο, και οι μελετητές έχουν δει ότι το θρησκευτικό φαινόμενο της λατρείας της εικόνας ξεκίνησε κατ' οίκον και στην Αίγυπτο, όπου η Μαρία έλαβε για πρώτη φορά το επίθετο Θεοτόκος, έναν τίτλο που κάποτε προοριζόταν για την Ίσιδα (Mathews 2005:47).

ΒΙΒΛΙΟΓΡΑΦΙΑ

Lyn Green, Royal Ontario Museum, Department of World Cultures

https://rom.academia.edu/LynGreen?fbclid=IwAR2TkFA-KIEix97DwJLbYAZJZ9-2apnK2qJSk0qx0NWQ2al4ALFzuCL_2eU

https://www.academia.edu/1154089/Queens_and_Princesses_of_the_Amarna_Period?fbclid=IwAR1VovihVB4h-F-5ctVdFXajUfZusvTpbrM8MNQLQDydgZAPrkpmfaSdq3g

Green, L. 1988. "Queens and Princesses of the Amarna Period" (diss. Univ. of Toronto).

https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0752/8/3/92

Barr, J., C. M. ten Berge, J. M. van Daal and B. F. van Oppen de Ruiter. 2019. "The Girl with the Golden Wreath: Four Perspectives on a Mummy Portrait," Arts 8(3), 92; https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030092

Hart, M. L. 2016. “A Portrait of a Bearded Man Flanked by Isis and Serapis,” in Icon, Cult, and Context: Sacred Spaces and Objects in the Classical World, ed. M. K. Heyn, A. I. Steinsapir, Ann I, Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, pp. 79-89.

Riggs, C. 2006. The Beautiful Burial in Roman Egypt: Art, Identity, and Funerary Religion, pl. 6, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

http://oi.uchicago.edu/pdf/saoc56.pdf

Corcoran, L. H. 1995. Portait Mummies from Roman Egypt (I-IV centuries), SAOC 56, Chicago.

Tarán, S. L. 1985. "Εἰσὶ τρίχες: An Erotic Motif in the Greek Anthology," The Journal of Hellenic Studies 105, pp. 90-107.

https://oi.uchicago.edu/sites/oi.uchicago.edu/files/uploads/shared/docs/saoc56.pdf

Montserrat, D. 1993. "The Representation of Young Males in 'Fayum Portraits'," The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 79, pp. 215-225.

σελ. 216-7: ηλικιακές κατηγορίες ανδρών: ἄωρος (untimely dead), ἄρτι γενειάσκων [αρτιγένειος], ἄρτι δ᾽ ἔρωτας ἐς θαλάμους καλέων

Anth. Pal. VII, 123,— Els Εὐφήμιον

Ῥήτωρ ἐν ῥητῆρσιν, ἀοιδοπόλος δ᾽ ἐν ἀοιδοῖς,

κῦδος ἑῆς πάτρης, κῦδος ἑῶν τοκέων,

ἄρτι γενειάσκων Εὐφήμιος, ἄρτι δ᾽ ἔρωτας

ἐς θαλάμους καλέων, ὥλετο' φεῦ παθέων"

ἀντὶ δὲ παρθενικῆς τύμβον λάχεν, ἠδ᾽ ὑμεναίων ὅ

ἤματα νυμφιδίων ἦμαρ ἐπῆλθε γόων.

p. 218

ceremonies of social inclusion. These typically include rituals of initiation at puberty, which can involve 'cultural work upon the body, and their effect is to transform the natural body into a social entity with rights and status.17 For the teenaged sons of the Hellenised elite in provincial Egypt, these rituals revolved around a public status declaration. in effect an affirmation of their membership of the paternal kin-group. This public status declaration or 'scrutiny` (επίκρισις or είσκρισις) confirmed the boy's lineage and his inclusion in one of several privileged groups eligible for fiscal and other privileges: the 'metropolitan twelve drachma class' (μητροπολίται δωδεκάδραχμοι), 'the gymnasium members' (οι από του γυμνασίου). or the ephebate (εφηβεία). Written declarations of επίκρισις or είσκρισις were usually made in the year when the declarant reached the age of thirteen or fourteen, thus becoming liable to pay the full rate of capitation lax. They state that the boy 'has entered into the class of thirteen (or fourteen)-year-olds' (προσβάντος εις τρισκεδεκαετείς / τεσσαρεσκαιδεκαετείς) in a given year.18 I have argued elsewhere''' that these status declarations signify more than a mere bureaucratic formality to gain tax relief, and that they were one component of an entire rites de passage system whose other elements could include 'cultural work upon the body' in the form of shearing off hair to mark transition, and also celebratory garlanding and banqueting. The epicrisis festivities could take place in important public buildings, such as the Capitolium, the traditional scene of Roman rites de passage.19 Formal enumeration of the hay's ancestry may also have played a part. Some icrisis declarations, such as P. Oxy. XVIII 2186, list forbears going back as far as seven generations, and these lists may well have been read out aloud at the time the document was drawn up or submitted. Reading out aloud would have served to underscore the boy's own name, (which characteristically followed that of a grandfather),21 and thus his standing and affiliation in the paternal kin-group, 'since having a name is an institutional mark of social membership.'22

The exact function and organisation in Roman Egypt of the other elite group for adolescents, the ephebate, is still unclear, as is its relationship to the Athenian body of youths with the same name and to the other selected social groups_ As P. Oxy. IV 7o5 tells us, some boys of the gymnasial class could be enrolled into it after a further examination of suitability. The length of a boy's ephebic service is uncertain, but was ..

p. 220

Conversely, there do not seem to be any purely Egyptian attestations of the wearing of moustaches by adolescents, which is unsurprising given the traditional Egyptian emphasis on hairlessness as a manifestation of physical and spiritual cleanliness. Furthermore, it would have been very difficult to indicate precise age categories within the representational canons of dynastic Egyptian art. The depiction of adolescent facial hair, therefore, suggests that we are dealing with a milieu in which the dominant cultural influence is Greek rather than Roman. This does not mean, however, that hair lacked symbolic potency in Pharaonic Egypt, or that rituals surrounding its shearing and preservation were Hellenistic innovations. At least as early as the New Kingdom, hair appears in contexts strongly suggestive of life-crisis rites.34 The showing of slight facial hair on the portrait of a young man, therefore, had a far wider symbolic value than might at first appear. It indicated that the deceased had died at a stage in his life when he was at his [NEXT PAGE IS 221]

p. 221

optimum sexual vitality and attractiveness, at least according to Hellenistic perceptions. It also made a statement about the social standing of the dead man as a Graeco-Egyptian who followed some Greek traditions associated with hair and puberty. Showing the moustache would have been one of the visual elements which helped to both idealise and eroticise the dead man so that he could be reborn in a perfect and vital form, in just the same way that Pharaonic tomb paintings can show a quintessential image or simulacrum of the deceased surrounded by erotic references.35 A variant set of symbols indicative of the connection between male physical vitality and bodily resurrection is found on the so-called 'tondo of the two brothers', found at Antinoopolis and how in Cairo (pl. XIII, I = Parlasca t, no. 166). The two men, both lightly moustached, ungarlanded and fully clothed, are flanked by golden figures of two syncretistic gods bath associated with death and renewal: Hermanubis on the viewer's right and Osirantinous on the left. Osirantinous is crowned and naked: as Hugo Meyer has suggested, his nudity is neither incidental nor erotic, but characteristic of the ephebe that he had been in life, and perhaps has further associations of the renaissance of Hellenism and Hellenic culture in Egypt under Hadrian.36 At the edge of the panel, by the pedestal of the Osirantinous statue, is the date 15 Pachon [Παχών] (early May). The younger-looking man on the viewer's left wears a white tunic, its right shoulder ornamented with a gammadion or swastika-like symbol composed of four Γ-shaped elements. This was later appropriated as a symbol of the trinity, the resurrection and of Christ himself,37 but in pre- Christianity it also had phallic connotations,38 making it an appropriate symbol for a context associated with death and rebirth. All in all, the Antinoοpolis tondo is an anomaly within the corpus of funerary portraits, and one wonders whether its unique format and array of symbols might commemorate something unusual about the two deceased men, such as the circumstances of death.39

p. 222: ephebate + garland

p. 223:

p. 270, Preisigke, F. 1915. Sammelbuch Griechischer Urkunden aus Ägypten, Strassburg : K.J. Trübner

https://archive.org/details/sammelbuchgriech00stra/page/n3/mode/2up

3990. Grabstein. Alexandria. Konstantinische Zeit. N&eroutsos, Rev.

arch. 9 (1887) 5. 201 Nr. 4.

Δάκρυσον εἰσορόων με | Διόσκορον Ἑλλάδος υἱόν, | τὸν σοφὸν

ἐν Μούσαις | καὶ νέον Ἡρακλέα.