Η εξάπλωση της δυτικής επιρροής: Αρχαία ελληνικά στοιχεία σε αντικείμενα των δυτικών περιοχών Κίνας

Αυτή η εικόνα απεικονίζει μια αρχαία τοιχογραφία από τις Σπηλιές Κιζίλ (Kizil Caves) στην Κίνα.

Πρόκειται για ένα κλασικό παράδειγμα της βουδιστικής τέχνης που αναπτύχθηκε κατά μήκος του αρχαίου Δρόμου του Μεταξιού.

Οι τοιχογραφίες αυτές χρονολογούνται κυρίως μεταξύ του 3ου και του 13ου αιώνα μ.Χ.

Απεικονίζουν σκηνές από τη ζωή του Βούδα, διδακτικές ιστορίες και την καθημερινή ζωή των ανθρώπων της εποχής.

Η τέχνη αυτή δείχνει έντονες επιρροές από τον ινδικό, τον ελληνιστικό και τον κινεζικό πολιτισμό, αναδεικνύοντας την πολιτιστική ανταλλαγή της περιοχής.

https://gs.ifeng.com/a/20200303/9835962_0.shtml

The Pearl of the Silk Road — Online Exhibition of Kucha Murals

https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_12696564

Η επιρροή της αρχαίας Ελλάδας μπορεί επίσης να εντοπιστεί στις διάσημες τοιχογραφίες των Σπηλαίων Κούτσα. Πρώτον, η γυμνή τέχνη στις τοιχογραφίες Κούτσα χρησιμοποιεί φωτοσκίαση για να τονίσει τους κυματιστούς μύες της ανδρικής κοιλιάς και των χεριών, και γραμμικό σχέδιο για να απεικονίσει τα απαλά, ολόσωμα σώματα των γυναικών. Επιπλέον, η κατανόηση των ανθρώπινων αναλογιών από τους καλλιτέχνες είναι εξαιρετικά ακριβής, όχι μόνο προσδίδοντας στις φιγούρες δυναμισμό και πληρότητα, αλλά και αποφεύγοντας τυχόν δυσανάλογα χαρακτηριστικά. Αυτό το καλλιτεχνικό στυλ επηρεάζεται κυρίως από την τέχνη της Γκαντάρα.

Λήψη προγράμματος-πελάτη

Σύνδεση

Προσιτότητα

+1

3

Η εξάπλωση της δυτικής επιρροής: Αρχαία ελληνικά στοιχεία σε αντικείμενα της δυτικής περιοχής

Ιστορική Ανακάλυψη

επικεντρωθείτε σε

2021-05-17 12:47

Σαγκάη

Πηγή: The Paper, The Paper Account, Paike

Ακούστε το πλήρες κείμενο

Μέγεθος γραμματοσειράς

Πρωτότυπες Ιστορικές Ανακαλύψεις του Horus από το Eagle Eye

Τα τελευταία χρόνια, η λεγόμενη ψευδοϊστορία της Ελλάδας έχει γίνει ανεξέλεγκτη, υποστηρίζοντας ότι ο αρχαίος ελληνικός πολιτισμός ήταν ένας κατασκευασμένος πρόγονος που δημιουργήθηκε από τους σύγχρονους Δυτικούς για να καλύψει την βαρβαρική τους προέλευση. Ωστόσο, η τεράστια χρονική έκταση και η γεωγραφική κατανομή των ελληνικών αντικειμένων εύκολα διαψεύδουν αυτή τη θεωρία. Στην πραγματικότητα, πολλά ιστορικά αντικείμενα εντός της Κίνας, που περιέχουν άμεσα ή έμμεσα στοιχεία της αρχαίας Ελλάδας, βρίσκονται, ειδικά στο Σιντσιάνγκ - ένα σταυροδρόμι ελληνικών, περσικών, ινδικών και κεντρικών πεδιάδων πολιτισμών - όπου τα ελληνικά στοιχεία είναι άφθονα σε διάφορα ιστορικά κειμήλια.Η τέχνη της Γκαντάρα χρησίμευσε ως σημείο διέλευσης για τη μετάδοση της ελληνικής τέχνης προς τα ανατολικά.

Αρχαίες ελληνικές μυθολογικές μορφές ανακαλύφθηκαν μαζί με διοικητικά έγγραφα

Στα τέλη του 1900 και στις αρχές του 1901, κατά τη διάρκεια αρχαιολογικών ανασκαφών στην περίφημη τοποθεσία Νίγια, ο Στάιν ανακάλυψε μια χωματερή που χρονολογείται από τα τέλη της δυναστείας Χαν έως την περίοδο των Τριών Βασιλείων στην Κίνα. Η χωματερή περιείχε διάφορα οικιακά απορρίμματα και αντικείμενα, που εξακολουθούσαν να αναδίδουν μια άσχημη οσμή περισσότερα από 2.000 χρόνια αργότερα. Ωστόσο, ανάμεσα σε ένα σωρό από θραύσματα κεραμικής, κομμάτια υφάσματος, άχυρου και δερμάτινα κομμάτια, βρέθηκαν μερικά διοικητικά ξύλινα χαρτάκια της δυναστείας Χαν. Μερικά από αυτά τα χαρτάκια έφεραν σφραγίδες που απεικόνιζαν Έλληνες θεούς. Αν και το στυλ έδειχνε ανατολικές επιρροές, παρέμεινε κλασικό αρχαίο ελληνικό:συμπεριλήφθηκαν εικόνες του Ερμή, του Δία, της Αθηνάς και του Ηρακλή. Ανακαλύφθηκαν επίσης σφραγίδες αξιωματούχων που κυβερνούσαν το Σανσάν. Οι χαρακτήρες "Σανσάν" ήταν ευανάγνωστοι ακόμη και μετά από περισσότερα από 2.000 χρόνια. Παραμένει άγνωστο αν οι αξιωματούχοι των Κεντρικών Πεδιάδων που χρησιμοποιούσαν αυτά τα χαρτάκια και τις σφραγίδες γνώριζαν τις ιστορίες που σχετίζονται με τις μυθολογικές μορφές που απεικονίζονται σε αυτές τις κυκλικές σφραγίδες. Κρίνοντας από τους κινεζικούς χαρακτήρες που ανακαλύφθηκαν την ίδια εποχή, η τελευταία καταγεγραμμένη προθεσμία ήταν το 269 μ.Χ., που ισοδυναμεί με τη βασιλεία του αυτοκράτορα Γου του Τζιν. Αυτό δείχνει ότι η δυναστεία των Κεντρικών Πεδιάδων, λόγω πολιτικής αστάθειας, δεν μπόρεσε να συνεχίσει να διαχειρίζεται την πόλη μετά από αυτή την περίοδο.Επίσης, στην τοποθεσία Νίγια ανακαλύφθηκε ένα τεχνούργημα που συνδυάζει την ανατολική και τη δυτική μυθολογία. Αυτό το ύφασμα απεικονίζει τόσο ανατολίτικες εικόνες δράκου όσο και μια ημίγυμνη Ελληνίδα θεά της συγκομιδής, που κρατάει ένα κέρας συγκομιδής. Αν και ο πίνακας περιέχει μοτίβα λιονταριού με ισχυρή περσική επιρροή, το κέρας της συγκομιδής στο χέρι της θεάς λειτουργεί ως σταθεροποιητική δύναμη, υπονοώντας τη σύνδεσή της με τον ελληνικό πολιτισμό. Αυτό το κέρας της συγκομιδής προέρχεται από την κατσίκα που θήλαζε τον Δία στην ελληνική μυθολογία. Επειδή ο Δίας κυνηγήθηκε από τον πατέρα του Κρόνο όταν ήταν βρέφος, η μητέρα του τον έκρυψε σε μια σπηλιά στην Κρήτη, όπου τον θήλασε μια κατσίκα. Αργότερα, αφού ο Δίας κατέλαβε τον θρόνο, ήταν πολύ ευγνώμων για το θηλασμό της κατσίκας. Έτσι, το σπασμένο κέρας της προβατίνας ήταν εμποτισμένο με θεϊκή δύναμη, επιτρέποντάς της να παράγει συνεχώς σιτηρά και φρούτα, και δόθηκε στη νύμφη που την είχε προστατεύσει στα νιάτα της. Μέχρι σήμερα, το κέρας της γονιμότητας είναι σύμβολο συγκομιδής και πλούτου στον δυτικό πολιτισμό. Αργότερα, το κέρας της γονιμότητας κρατούσε η Τύχη, κόρη του Δία και Ελληνίδα θεά της συγκομιδής. Ωστόσο, στην ταπισερί Niya, το στέμμα της θεάς αντικαθίσταται από ένα φωτοστέφανο που θυμίζει τον πολιτισμό Gandhara.Το κέρας της γονιμότητας απεικονίζεται σε αγγεία καισε αρχαία ελληνικά νομίσματα που φέρουν τον Δία.

Η εικόνα του Ερμή: Η επίδραση των αρχαίων ελληνικών εμπορικών δραστηριοτήτων στις δυτικές περιοχές

Εκτός από τους ανθρώπους των Κεντρικών Πεδιάδων, άλλοι λαοί της Ινδοευρωπαϊκής φυλής στα μικρά βασίλεια των Δυτικών Περιοχών παρουσίαζαν επίσης πιο διακριτικά ή εμφανή ελληνικά στοιχεία στην καθημερινή τους ζωή. Για παράδειγμα, ο Stein ανακάλυψε ένα θραύσμα υφάσματος με ανθρώπινη κεφαλή ελληνικού τύπου και ένα ιερό τεχνούργημα στον τάφο ενός τοπικού ευγενή έξω από το Loulan. Όσοι είναι εξοικειωμένοι με την ελληνική μυθολογία θα αναγνωρίσουν αυτό το σύμβολο. Αυτό το τεχνούργημα ονομάζεται Ραβδί του Ερμή. Ο νεαρός άνδρας στο ύφασμα είναι ο Ερμής, ο γιος του Δία, του θεού του εμπορίου και του αγγελιοφόρου.

Το Ραβδί του Θεού του Εμπορίου, που εξακολουθεί να αναφέρεται ευρέως σήμερα

Στην αρχαία ελληνική μυθολογία, ο Ερμής ήταν πονηρός και ύπουλος από τη φύση του. Ωστόσο, λόγω της νοημοσύνης, της ευκινησίας και της ικανότητάς του να κινείται γρήγορα φορώντας φτερωτές μπότες, θεωρούνταν από τους αρχαίους Έλληνες εμπόρους ως ο προστάτης άγιος των ταξιδιών μεγάλων αποστάσεων και του διεθνούς εμπορίου.

Άγαλμα του Ερμή

Λαμβάνοντας υπόψη τα αρχεία Kharosthi, σύμφωνα με τα οποία το Βασίλειο Loulan χρησιμοποιούσε αρχαίες ελληνικές μονάδες μέτρησης και κυκλοφορούσε αρχαίο ελληνικό νόμισμα, όπως η δραχμή και το έθνος, το άγαλμα του Ερμή πιθανότατα μεταφέρθηκε εδώ από αρχαίους Ελληνορωμαίους εμπόρους. Η ανακάλυψη του σκήπτρου του θεού του εμπορίου στο Loulan αποτελεί μεταφορά για το προηγμένο διεθνές εμπόριο του ελληνιστικού κόσμου.

Ο Στάιν ανακάλυψε ένα μοτίβο σε ένα ύφασμα του Ερμή που κρατούσε ένα σκήπτρο.

Επιπλέον, τα ελληνικά παγκόσμια νομίσματα εμφανίστηκαν επίσης σε μεγάλες ποσότητες στην αρχαία Σιντζιάνγκ. Τα ακόλουθα αντικείμενα προέρχονται από το Μουσείο Ακσού:

Ρούχα μικτού στυλ όμορφων ανδρών στο Γινγκπάν

Το 1989, το Ινστιτούτο Πολιτιστικών Κειμηλίων και Αρχαιολογίας του Ξιντσιάνγκ ανακάλυψε ένα καλοδιατηρημένο ανδρικό πτώμα ντυμένο με υπέροχα ρούχα σε έναν αρχαίο τάφο στο Γινγκπάν του Ξιντσιάνγκ. Αυτός ο ευγενής της Δυτικής Περιοχής, γνωστός ως ο «Όμορφος Άνδρας του Γινγκπάν», είχε ύψος 180 εκατοστά, ανοιχτόχρωμα καστανά μαλλιά και τρίχες στο σώμα. Πιθανότατα ήταν ευγενής από το κοντινό βασίλειο Μοσάν, περίπου 30 ετών, και έζησε κατά την περίοδο Χαν-Τζιν. Όταν ανακαλύφθηκε το σώμα του, φορούσε μια στενή ρόμπα σε στυλ Κεντρικής Ασίας και το πρόσωπό του ήταν καλυμμένο με μια καλοδιατηρημένη μάσκα κάνναβης. Η μάσκα είχε ύψος 25 εκατοστά, ελαφρώς μεγαλύτερη από το πρόσωπο του νεκρού, με μακριές λωρίδες χρυσού φύλλου στο μέτωπό του. Η μάσκα ήταν εξαιρετικά κατασκευασμένη. Το πρόσωπό του ήταν βαμμένο λευκό, με μαύρη βαφή που χρησιμοποιήθηκε για να τονίσει τα μάτια, τα χείλη και την ψηλή γέφυρα της μύτης του. Στη συνέχεια, εφαρμόστηκε κόκκινη βαφή στα χείλη του. Τα μάτια και το στόμα του ήταν κλειστά και τα φρύδια του ήταν πολύ λεπτά και μακριά. Η μάσκα ήταν κατασκευασμένη με έναν πολύ μοναδικό τρόπο. Αρχικά, κατασκευάστηκε μια μεμβράνη ανθρώπινου προσώπου από ξύλο και πηλό. Στη συνέχεια, επικολλήθηκε λινό ύφασμα πάνω της και οι κοίλες γραμμές των ματιών και των χειλιών σχεδιάστηκαν με ένα σκληρό αντικείμενο. Αφού στέγνωσε το λινό ύφασμα, η μεμβράνη αφαιρέθηκε και εφαρμόστηκε λευκό χρώμα στο πρόσωπο. Χρησιμοποιήθηκε μαύρο χρώμα για να σκιαγραφηθούν τα φρύδια, οι σχισμές των ματιών και το μουστάκι, αντανακλώντας τα τυπικά χαρακτηριστικά αυτού του ατόμου της ευρωπαϊκής φυλής.

Αξιοσημείωτο είναι ότι φοράει μια κόκκινη ρόμπα στολισμένη με συμμετρικά ελληνορωμαϊκά μοτίβα αγγέλων και πολεμιστών σε μονομαχία, με τους άγγελους και τους πολεμιστές να έχουν σαφώς τις ρίζες τους στην ελληνική παράδοση. Μια πιο προσεκτική ματιά αποκαλύπτει τα ζευγαρωμένα πολεμιστές, ίσως παραπέμποντας στους δίδυμους πολεμιστές της ελληνικής μυθολογίας: τον Κάστορα και τον Πολύδοξο, γιους της Λήδας, βασίλισσας της Σπάρτης, και το αρχέτυπο του αστερισμού των Διδύμων. Στην πραγματικότητα, το μοτίβο του δίδυμου πολεμιστή είναι ένα κοινό θέμα στην αρχαία ινδοευρωπαϊκή μυθολογία, με παρόμοιες εκδοχές να βρίσκονται στην αρχαία Ινδία, την αρχαία Ελλάδα και τους λαούς της Βαλτικής. Επομένως, αυτή η απεικόνιση δεν θα ήταν άγνωστη στην αριστοκρατία των αρχαίων δυτικών περιοχών.

Φυσικά, μερικοί πιστεύουν ότι αυτός είναι ο Έρωτας, ο θεός της αγάπης, και όποιος χτυπηθεί από το χρυσό βέλος ή το μαγικό ραβδί του Έρωτα θα κερδίσει αγάπη, ενώ όποιος χτυπηθεί από το μολύβδινο βέλος του θα χάσει αγάπη.

Ωστόσο, η συμμετρική διάταξη διαφόρων μοτίβων κάτω από το δέντρο είναι μια παράδοση της αρχαίας Περσίας. Εκτός από διάφορα ταφικά αντικείμενα με ελληνικά και περσικά στοιχεία, βρέθηκαν επίσης το φέρετρο με ζωγραφισμένο ένα τρίποδο χρυσό κοράκι, κρίνους και έναν φρύνο στο φεγγάρι, ένας χάλκινος καθρέφτης με τέσσερις θηλές και τέσσερα φίδια, ένα μπροκάρ προστατευτικό μπράτσου με σχέδια δράκου και θηρίου, και ένα πάνελ στο καπάκι του φέρετρου ζωγραφισμένο με ένα τετράποδο μυθικό θηρίο. Αυτά τα αντικείμενα έχουν σαφώς τα χαρακτηριστικά του πολιτισμού των Κεντρικών Πεδιάδων, υποδεικνύοντας ότι αυτό το άτομο όχι μόνο επωφελήθηκε από το εμπόριο του Δρόμου του Μεταξιού, αλλά μπορεί επίσης να έλαβε ανταμοιβές από τη δυναστεία των Κεντρικών Πεδιάδων.

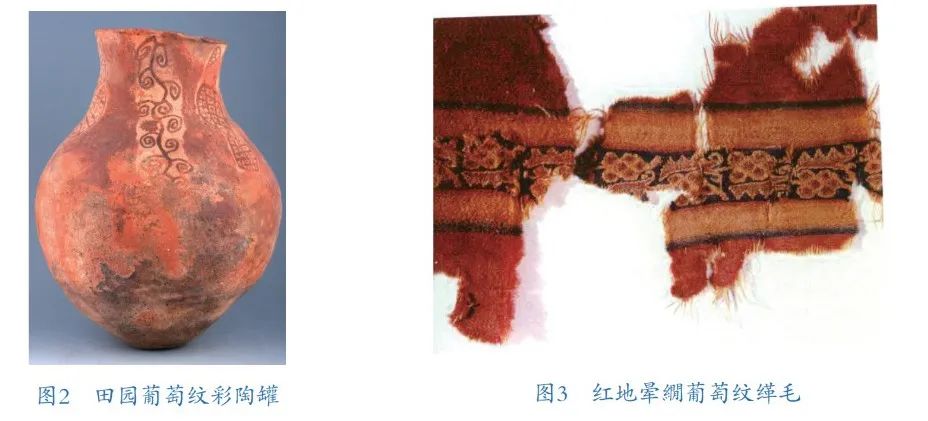

Κουλτούρα σταφυλιού και κρασιού στις Δυτικές Περιοχές

Εκτός από τα ελληνικά μοτίβα και τα σχέδια σφραγίδων, ορισμένα αντικείμενα υποδηλώνουν ότι ο αρχαίος ελληνικός τρόπος ζωής μπορεί επίσης να επηρέασε τους ανθρώπους των Δυτικών Περιοχών. Για παράδειγμα, ένα μαύρο μελανοδοχείο που ανακαλύφθηκε στο Κασγκάρ του Σιντσιάνγκ το 1977 απεικονίζει μια σκηνή ποτού, κοινή στον αρχαίο ελληνικό πολιτισμό: δύο άνδρες σερβίρουν κρασί σε έναν ανακλινόμενο καναπέ, ετοιμαζόμενοι να πιουν μαζί. Ένας άνδρας είναι γυμνός, αποκαλύπτοντας το μυώδες στήθος του. Σε σύγκριση με την αρχαία ελληνική εκδοχή της σκηνής ποτού, η εκδοχή του Κασγκάρ έχει πιο συμπαγείς και αρχαϊκές γραμμές, και οι μορφές είναι σχετικά όρθιες, δείχνοντας την επιρροή της τέχνης της Γκανταράν.(Αρχαία ελληνική κεραμική που απεικονίζει μια σκηνή ποτού .)

Στην αρχαία Ελλάδα, τέτοιες συγκεντρώσεις κρασιού ενέπνευσαν το αθάνατο φιλοσοφικό αριστούργημα, *Συμπόσιο*. Παρόμοιες σκηνές εμφανίζονται συχνά σε διάφορες κλασικές αγγειογραφίες και τοιχογραφίες. Εκτός από την ευρεία κατανομή των Ελλήνων τεχνιτών και εμπορικών κοινοτήτων στην Εσωτερική Ασία, το κλίμα και η γεωγραφία των Δυτικών Περιοχών και της Φεργκάνα ευνοούσαν επίσης την παραγωγή σταφυλιών υψηλής ποιότητας. Επομένως, η κουλτούρα του κρασιού από την Ελλάδα πιθανότατα είχε και μια αγορά στις αρχαίες Δυτικές Περιοχές και διέθετε την τοποθεσία και το πολιτιστικό έδαφος για να ριζώσει: για παράδειγμα, όταν ο Λου Γκουάνγκ οδήγησε τα στρατεύματά του δυτικά προς την Κούτσα το 384 μ.Χ., τα πλούσια νοικοκυριά εκεί «αγαπούσαν τη διατήρηση της υγείας, κατέχοντας έως και χίλια μπούσελ κρασιού, το οποίο παρέμεινε ανέγγιχτο για δέκα χρόνια». Τα πολυάριθμα αντικείμενα και λείψανα με σχέδια σταφυλιών που σχετίζονται με τον Διόνυσο, τον θεό του κρασιού, που ανακαλύφθηκαν στο Σιντσιάνγκ υποδηλώνουν επίσης ότι η κουλτούρα του σταφυλιού έχει τις ρίζες της σε αυτή τη γη από την αρχαιότητα.

Ένα πήλινο βάζο με τρεις λαβές και περσική εφυαλωμένη κατασκευή που ανακαλύφθηκε στο Ακσού περιλαμβάνει εικόνες τουΔιονύσου, του Έρωτα, του Ήλιου και του Ηρακλή, αρχαία ελληνικά στοιχεία που βρέθηκαν σε θρησκευτικές τοιχογραφίες και γλυπτά.

Εκτός από διάφορα κοσμικά καθημερινά αντικείμενα, αρχαία ελληνικά στοιχεία, είτε έμμεσα είτε άμεσα, μπορούν επίσης να βρεθούν σε διάφορες θρησκευτικές τοιχογραφίες. Με την εξάπλωση του Βουδισμού προς τα ανατολικά, η τέχνη της Γκαντάρα εισήχθη και στις δυτικές περιοχές.

Το φόντο του πίνακα «Άγγελοι του Μιλάνου»είναι μια βουδιστική τοιχογραφία σε κόκκινο χρώμα της Πομπηίας, με ορισμένους πίνακες να ενσωματώνουν καλλιτεχνικά στυλ από την ελληνιστική περίοδο.

Το 1907, ο Βρετανός αρχαιολόγος Aurel Stein ανακάλυψε βουδιστικά ερείπια στην έρημο του Μιλάνου, συμπεριλαμβανομένων εικόνων φτερωτών αγγέλων. Αυτές οι εικόνες προέρχονταν από την τέχνη της Γκαντάρα στην Κεντρική Ασία, και οι εικόνες αγγέλων στην τέχνη της Γκαντάρα προέρχονταν από τον Έρωτα, τον Έλληνα θεό του έρωτα.

Ο αυθεντικός Έρωτας από την αρχαία Ελλάδα

Αφού ένας μεγάλος αριθμός Ελλήνων τεχνιτών εισήλθε στην Κεντρική Ασία και τη Βόρεια Ινδία, η εικόνα αυτού του φτερωτού αγγέλου δανείστηκε ευρέως από τους τοπικούς καλλιτέχνες στην Ινδία και αργότερα στις Δυτικές Περιοχές.

Ο άγγελος Έρωτας στην τέχνη των Δυτικών Περιοχών έχει ένα πιο στρογγυλεμένο και πληρέστερο σώμα·η εικόνα του αγγέλου στο διάσημο κιβώτιο λειψανοθήκης Kuqa.

Όσον αφορά το γιατί εμφανίστηκαν άγγελοι στο Μιλάνο, ο Στάιν ανακάλυψε ότι δίπλα σε έναν από τους πίνακες με τους αγγέλους βρισκόταν η υπογραφή του καλλιτέχνη, Τίτος. Το όνομα Τίτος ήταν ένα από τα κοινά ονόματα που χρησιμοποιούσαν οι Ρωμαίοι εκείνη την εποχή. Ίσως κάποιος καλλιτέχνης που είχε εκπαιδευτεί στην ελληνορωμαϊκή τέχνη διέσχισε την έρημο στο Μιλάνο και έφερε μαζί του διάφορες μορφές από την ελληνορωμαϊκή μυθολογία.

Εκτός από τον Έρωτα, ο Στάιν ανακάλυψε επίσης έναν πίνακα στις τοιχογραφίες του βουδιστικού ναού στα ερείπια του Μιλάνουστο Σιντζιάνγκ, που απεικονίζει μια σκηνή από το ελληνικό επικό ποίημα «Οι Κύκλωπες». Ο πίνακας δείχνει έναν μυώδη νεαρό πολεμιστή να κρατάει ένα ρόπαλο και να μάχεται με ένα φτερωτό λιοντάρι, τον Γρύπα.

Αυτή η σκηνή βασίζεται στο μακροσκελές αφηγηματικό ποίημα *Αρίμασπάς* του Έλληνα βάρδου Αριστία. Αυτός ο ποιητής ταξίδεψε στην Κεντρική Ασία στα τέλη του 7ου αιώνα π.Χ., επισκεπτόμενος την Ισηδονική φυλή των Σκυθών. Άκουσε από τους ντόπιους για τη φυλή Αριμασπάς, που σημαίνει «μονόφθαλμη φυλή», η οποία συγκρούονταν συχνά με τα φτερωτά μυθικά θηρία, τους γρύπες, που φύλαγαν τα αποθέματα χρυσού των Αλτάι. Λίγο μετά την επιστροφή του στην πατρίδα του, ο Αριστίας συνέθεσε το μακροσκελές αφηγηματικό ποίημα *Αρίμασπάς*.

Σκηνές από ελληνικά έπη σε τοιχογραφίες του Μιλάνου, συμπεριλαμβανομένων μαχών μεταξύ γιγάντων και γρυπών,αποτελούν τα πρωτότυπα για ιστορίες στα αρχαία ελληνικά έπη.

Όταν ο Ηρόδοτος αργότερα αφηγήθηκε την ιστορία των φυλών της στέπας της Κεντρικής Ασίας, αναφέρθηκε σε αυτό το επικό ποίημα. Η ιστορία ενσωματώθηκε αργότερα στην ελληνική μυθολογία και έγινε συχνό θέμα για τους καλλιτέχνες. Παρόλο που οι Έλληνες απόγονοι ή οι Ινδοί καλλιτέχνες στην καρδιά της Ασίας δεν γνώριζαν πλέον την αρχική σημασία αυτού του μοτίβου, συνέχισαν να μιμούνται και να αντιγράφουν την τεχνική.

Η επιρροή της αρχαίας Ελλάδας μπορεί επίσης να εντοπιστεί στις διάσημες τοιχογραφίες των Σπηλαίων Κούτσα. Πρώτον, η γυμνή τέχνη στις τοιχογραφίες Κούτσα χρησιμοποιεί φωτοσκίαση για να τονίσει τους κυματιστούς μύες της ανδρικής κοιλιάς και των χεριών, και γραμμικό σχέδιο για να απεικονίσει τα απαλά, ολόσωμα σώματα των γυναικών. Επιπλέον, η κατανόηση των ανθρώπινων αναλογιών από τους καλλιτέχνες είναι εξαιρετικά ακριβής, όχι μόνο προσδίδοντας στις φιγούρες δυναμισμό και πληρότητα, αλλά και αποφεύγοντας τυχόν δυσανάλογα χαρακτηριστικά. Αυτό το καλλιτεχνικό στυλ επηρεάζεται κυρίως από την τέχνη της Γκαντάρα.Επιπλέον, το τοπικό έθιμο στην Κούτσα - «ανατολικά των βουνών Παμίρ, οι άνθρωποι αγαπούν την ασυδοσία. Η Κούτσα και ο Χοτάν έχουν ιδρύσει οίκους ανοχής, χρεώνοντάς τους χρήματα» - παρείχε μεγάλο αριθμό εταίρων ως άμεσα διαθέσιμα γυμνά μοντέλα, δημιουργώντας έτσι εύφορο έδαφος για αυτή την εκθαμβωτική μορφή τέχνης.

Εκτός από τα ελληνικά μοτίβα και τα σχέδια σφραγίδων, ορισμένα αντικείμενα υποδηλώνουν ότι ο αρχαίος ελληνικός τρόπος ζωής μπορεί επίσης να επηρέασε τους ανθρώπους των Δυτικών Περιοχών. Για παράδειγμα, ένα μαύρο μελανοδοχείο που ανακαλύφθηκε στο Kashgar του Xinjiang το 1977 απεικονίζει μια σκηνή πόσεως, κοινή στον αρχαίο ελληνικό πολιτισμό: δύο άνδρες σερβίρουν κρασί σε έναν ανακλινόμενο καναπέ, ετοιμαζόμενοι να πιούν μαζί. Ένας άνδρας είναι γυμνός, αποκαλύπτοντας το μυώδες στήθος του. Σε σύγκριση με την αρχαία ελληνική εκδοχή της σκηνής ποτού, η εκδοχή του Kashgar έχει πιο συμπαγείς και αρχαϊκές γραμμές, και οι μορφές είναι σχετικά όρθιες, δείχνοντας την επιρροή της τέχνης της Gandhara.

Εκτός από τα ελληνικά μοτίβα και τα σχέδια σφραγίδων, ορισμένα αντικείμενα υποδηλώνουν ότι ο αρχαίος ελληνικός τρόπος ζωής μπορεί επίσης να επηρέασε τους ανθρώπους των Δυτικών Περιοχών. Για παράδειγμα, ένα μαύρο μελανοδοχείο που ανακαλύφθηκε στο Kashgar του Xinjiang το 1977 απεικονίζει μια σκηνή πόσεως, κοινή στον αρχαίο ελληνικό πολιτισμό: δύο άνδρες σερβίρουν κρασί σε έναν ανακλινόμενο καναπέ, ετοιμαζόμενοι να πιούν μαζί. Ένας άνδρας είναι γυμνός, αποκαλύπτοντας το μυώδες στήθος του. Σε σύγκριση με την αρχαία ελληνική εκδοχή της σκηνής ποτού, η εκδοχή του Kashgar έχει πιο συμπαγείς και αρχαϊκές γραμμές, και οι μορφές είναι σχετικά όρθιες, δείχνοντας την επιρροή της τέχνης της Gandhara. (Αρχαία ελληνική κεραμική που απεικονίζει μια σκηνή ποτού .)

(Αρχαία ελληνική κεραμική που απεικονίζει μια σκηνή ποτού .)

Διονύσου, του Έρωτα, του Ήλιου και του Ηρακλή, αρχαία ελληνικά στοιχεία που βρέθηκαν σε θρησκευτικές τοιχογραφίες και γλυπτά.

Διονύσου, του Έρωτα, του Ήλιου και του Ηρακλή, αρχαία ελληνικά στοιχεία που βρέθηκαν σε θρησκευτικές τοιχογραφίες και γλυπτά. Το φόντο του πίνακα «Άγγελοι του Μιλάνου

Το φόντο του πίνακα «Άγγελοι του Μιλάνου »

» είναι μια βουδιστική τοιχογραφία σε κόκκινο χρώμα της Πομπηίας, με ορισμένους πίνακες να ενσωματώνουν καλλιτεχνικά στυλ από την ελληνιστική περίοδο.

είναι μια βουδιστική τοιχογραφία σε κόκκινο χρώμα της Πομπηίας, με ορισμένους πίνακες να ενσωματώνουν καλλιτεχνικά στυλ από την ελληνιστική περίοδο.

Ο άγγελος Έρωτας στην τέχνη των Δυτικών Περιοχών έχει ένα πιο στρογγυλεμένο και πληρέστερο σώμα·

Ο άγγελος Έρωτας στην τέχνη των Δυτικών Περιοχών έχει ένα πιο στρογγυλεμένο και πληρέστερο σώμα·

Εκτός από τον Έρωτα, ο Στάιν ανακάλυψε επίσης έναν πίνακα στις τοιχογραφίες του βουδιστικού ναού στα ερείπια του Μiran

Εκτός από τον Έρωτα, ο Στάιν ανακάλυψε επίσης έναν πίνακα στις τοιχογραφίες του βουδιστικού ναού στα ερείπια του Μiran

Σκηνές από ελληνικά έπη σε τοιχογραφίες του Miran, συμπεριλαμβανομένων μαχών μεταξύ γιγάντων και γρυπών, αποτελούν τα πρωτότυπα για ιστορίες στα αρχαία ελληνικά έπη.

Σκηνές από ελληνικά έπη σε τοιχογραφίες του Miran, συμπεριλαμβανομένων μαχών μεταξύ γιγάντων και γρυπών, αποτελούν τα πρωτότυπα για ιστορίες στα αρχαία ελληνικά έπη.