ΤΟ ΜΕΤΑΞΙ ΣΤΗΝ ΚΙΝΑ ΤΩΝ HAN (Sengupta)

Hermes woolen tapestry, Loulan, 1st-2nd century CE, New Delhi: National Museum of India[0]

Preface

THE very notion of silk was shaped by China's adventure with sericulture. It profoundly affected the economic and cultural development of the ancient world. The rarity and antiquity of textiles from Sir Marc Aurel Stein's three expeditions are best conveyed by Stein's assistant Fred Andrews who in his article in The Burlington Magazine (1920) stated that "the first impression of a casual examination of the specimens was the absence of general resemblance to anything in textiles with which we are familiar". Commencing from Stein's crucial discovery of burial silks in the Tarim Basin in 1913, over 2,000 textile fragments have been recovered during three of his expeditions in the first two decades of the twentieth century. Sir Stein's gigantic contribution to Central Asian archaeology was due to his amazing stamina, courage, intuition, and luck. The varieties of textile excavated by him span several centuries, from the first century BCE to the eleventh century CE. Classified by the sites of their discovery, relics from Loulan and Astana constitute the majority. The exotic fragments were shared between the museums in London and New Delhi. Parts of the Stein Collection in London include those in the British Museum and some 700 textiles on loan to the Victoria and Albert Museum. The importance of over 600 textile pieces in the National Museum at New Delhi cannot be underemphasized. The deliberation on the high quality and artistic value of the Stein Collection in India is intended to fill a lacuna and realize at least in part the worldwide interest to study a significant segment of the Stein Collection not in view. This was made possible by the liberal consent of Kuniko Ono, the publisher of Shikosha Artbooks. First published in Japan in 1979, the reproduction of the Stein Collection in Fabrics from the Silk Road in the National Museum of India has helped to exemplify Sir Stein's Central Asian expedition in the four volumes of Innermost Asia published in 1928.

Besides Stein's assemblage, Central Asian burial textile in the State Hermitage Museum in Leningrad is a major collection. Our knowledge of antique textile comes mainly from these museum pieces. Archaeological textile studies are an important source of information for anthropological and technological inquiry. At Copenhagen John Becker's reconstruction of Han Pattern and Loom resulted in the instructive A Practical Study of the Development of Weaving Techniques in China, Western Asia and Europe first published in 1986. Moreover color is the single most remarkable quality of any Central Asian textile. The sources of natural dyes and method of fixing hold a number of clues. The discovery of heritage textiles from Central Asia and China is comparatively recent. Even so, the admirable work of scholars and ever-growing demand in a collector's market have increased the number of publications on ancient textiles in museums and art galleries. The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Cleveland Museum of Art came together and held an exhibition of the Asian textiles dating from the eighth to the early fifteenth century CE. The catalog When Silk Was Gold: Central Asian and Chinese Textiles published in 1997 by the collaborating museums admirably fulfilled a function in this category. Since 1950 the second period in archaeological excavation of textiles was undertaken by the People's Republic of China in well over 100 burial sites in south central China, Mangolia and Central Asia. In collaboration with worldwide institutions The Silk Road International Dunhuang Project documentation makes research in this area infinitely expandable.

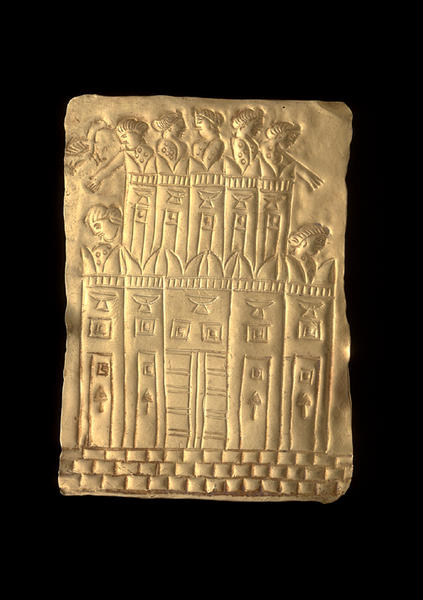

The mysterious innovations in silk weaving in Central Asia are astonishing in the light of the fact that the technology was known for centuries in West Asia. Chinese Central Asia without the proto-weaving techniques of twining and plaiting suddenly accomplished sericulture and professional silk weaving. The fully developed and technically unsurpassed figure weaves from a landlocked region defined by its deserts, inhospitable climate and limited rainfall are rather mysterious. The greatest advantage was the native mulberry bush in the rearing of Bombyx mori for the finest and longest of silken thread. The convergence of sericulture and silk weaving had definitive form and function. Exposed to freezing nights and searing heat during the day, graves yielded stunning silk furnishing symptomatic of a drastic change in funerary customs. Ethno- archaeology not only reveals technical excellence in weaving but also offers proof of faith in afterlife. The discovery of these historic fabrics preserved in Japan, Africa and Europe exposes their identity and character. In addition, the textile designs actually have a notable function in Parthian and Greco-Buddhist architectural reliefs in Persia and South Asia. Riboud's discussion on Han dynasty textiles compares the animal style to early Indian sculpture. The shared motifs in mortuary art indicate that a full exploration in this direction is a challenging but a rewarding task. When that cultural context is not acknowledged a great amount of historical realism is also lost. To address this problem consideration of religious symbolism, funerary customs and folklore inherent to the burial silk and artifacts recovered along the Silk Road is essential.

As the most preferred funerary goods silk worth its weight in gold is the most significant factor in the trade along the Silk Road. Caught in the dynamics of history are the geopolitical plot and the emerging distinction between China, Inner Asia and Eurasia in the geographical sense of the term. It was not yet populated by either self- contained or self-defined nationalities. Ethnically and culturally indistinct nationalities intermingled in the Crossroads of Asia. As the carriers of ideas and commodities and also religions, merchants and travelers not only connected Mongolia-China with Syria, Turkey, and Egypt but several of them even adopted new homelands. Commercial contacts have a longer lasting life and an immense potential to cement the bonds between various countries. As a result, the Greco-Buddhist reliquary cult in South Asia flourished precisely due to the lucrative silk trade with Rome. It is in this light that several of the figured textiles will be viewed in terms of their affirmed function. One of the astonishing by-products of the Silk Road is the jade garment. Depending on the station of the person buried, body suits made of pieces of jade are exceptional. These are fashioned mostly with square or rectangular and occasionally triangular, trapezoid and rhomboid plaques knitted together by gold, silver or copper wire. The most fabulous among these is the jade burial suit at the Mausoleum Museum of the Nanyue King in Cuangzhou. The "patchwork suit" is made of 2,291 pieces of jade pieces connected by red silk thread or silk ribbon overlapping the edges of the plaques. The world's oldest textile printing blocks in bronze from this Han tomb are also part of the Nanyue culture. Indicating that Guangzhou in the ancient Silk Route was exposed to diverse influences, the tomb contained in addition to extraordinary Chinese burial goods, five African elephant tusks, frankincense and a silver box from Persia.

Patchwork robe refers to clothing pieced together from bits of precious cloth. It indicates that even small pieces of textile fragments were treasured. Seated Buddha from the Mathura school in north India wears scraps of fabric sewn together. A votive frieze from Amaravati (now in Los Angeles) also depicts patchwork garment with square patches. In philosophic terms the "patchwork robe of salvation" in the Greco- Buddhist cult might be a treasured spiritual vestment or simply a skillful means of teaching (upaya):

Zen master Tongan asked, "What is the business under the patchwork robe?" Liangshan had no answer.

Tongan said, "It is wretched if you don't reach this state. You ask me and I'll tell you."

Introduction

The main commodity in the international trade was silk produced in China. Seres, the Greek word for silk, became synonymous for China, the land of silk. The Latin serieum is derived from the Greek ser. The adoption of Greek and Latin words for silk is evident in other languages: sieg in Chinese, modern ssu for silk thread, sir in Korean, sirket in Mongolian, seale in Russian, and silk in English. Referring to the ancient overland silk trade routes, the nineteenth-century German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen first coined the word Seidenstrassen or Silk Road between East and West. Most of the medieval sources refer to the famous highway as Big Route (botshaom targovam puti) or Shawari Caravan (Shahrahibuzurg) and even as Silk Road (Rahiabrasnami) To reach the Syrian markets it had to cross the deserts and mountains of Asia. Along the most dangerous stretches of the route fortified strongholds were built to protect the precious caravans. In the first centuries of the Christian era Hatra in Iraq among the great Parthian cities continued to flourish as a major Arab staging-post. In the chain Hatra linked Palmyra (sacked CE 272) and Dura-Europos in Syria (deserted CE 256), Petra in Jordan (declined CE 235), and Baalbeck in Lebanon, all having the eclectic identity of a mixed population merged with the Greek settlers. Pliny the Elder and others identify Petra, the capital of the Nabataeans, as the center of caravan trade. The caravan route of the Silk Road branched off at certain points for practical purpose. In Bactria the route turned southwards, continuing by sea through the Persian Gulf and then to Alexandria by way of the Red Sea. Thus on its western end the Silk Road began on the Mediterranean coast, in the ports of Alexandria and Antioch. It wound its way through the caravan cities in northern Iran, Chorasrnia and Ferghana, and then through western Turkistan, notably the city of Samarkand in Sogdiana. The arterial route then scaled the Pamir range, the Roof of the World. It then became the T'ien Shan South Road that skirted the Takla Makan Desert, passing through such oasis towns as Kashgan and Kucka along the way. Entering China through Loulan or Dunhuang, the Silk Road finally reached Ch' ang-an, the city known today as Sian (0.1). To the Han the economic factor of silk was significant. A speech by the Grand Secretary to the early western Han Council recorded in 81 BCE proclaims the importance of silk trade with the nomad tribes in the north:

For a piece of Chinese plain silk article several pieces of gold can be exchanged with the Hsiung-nu, and thereby reduce the resources of our enemy. Thus mules, donkeys and camels cross the frontier in unbroken lines; horses, dapples and bays and prancing mounts, come into our possession. The furs of sables, marmots, foxes and badgers, colored rugs and decorated carpets fill the imperial treasury, while jade and auspicious stones, corals and crystals become national treasures.

Above all, the supply of lustrous silk to Rome by way of Parthia and Palmyra filled the coffers of the eastern kingdoms. And as planned, it also reduced the vital resources of their common enemy. The Syrian glass factories established at this time in Central Asia were probably part of the reciprocal exchange between China and Syria. By shifting important local industries from the subject nations, there appears to be a concerted effort to deny Rome the benefits of its imperial power. This ploy made Rome pay exorbitant amounts of gold to buy the luxurious silk and precious gems, cut glasses and crystals, aromatics and medicines, as well as wine from Ferghana it craved for. Pliny complained that the luxury goods were depleting the Roman treasury to the extent of fifty million sesterces annually.' A vital section of the Silk Route was owned by the Parthians and due to concerns caused by the expansionism of Rome, for about fifty years silk intended for Rome traveled through Media, Armenia and on to Colchis and the Black Sea coast. In CE 66 the ploy of crowning the Parthian ruler Trididates in Rome did not yield expected results and the Sasanians who supplanted Parthians continued to resist the advances of Rome and levied heavy taxes on the caravans passing through their territories.

The Silk Route

Roughly the size of Australia, Central Asia covers the immense expanse of the empire of the steppes called Russian and Chinese Turkistan. The overland caravan contact along the southern limits of the region became possible with the domestication of the Bactrian camel in the first centuries of the Common Era (0.2). Following camel trails nomads in the Eurasian Kazakhstan still gallop across the steppes and the high mountain pass. Ancient traditions are kept alive by the craftsmen in the vibrant markets and caravanserais of Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Xinjiang. It is a mysterious land of myths and legends in which the Silk Road has left behind ruined cities and tombs. The Chinese autonomous Province of Xinjiang has Takla Makan Desert and Kunlun Mountains in the south sharing borders with Tibet and Pakistan where Gilgit is located on the ranges of Karakoram. The major sites in Xinjiang are Loulan, Astana, Niya, Bezeklik, Taxkurgan and Fiaoche. In Western Kinghay, cultural counterparts of Xinjiang are Sholak Korgon, Koshoy Korgon, Shirdakbek, Lap Nor and Gandhara. Consequent to Alexander's conquest, Sogdiana between River Amu Darya and Syr Darya played an important role in the religious and cultural development of Central Asia. Until the eighteenth century, the merchants who took the hazardous journey were mostly Sogdians, a Greco-Iranian people (0.3). Thereafter the Uyghurs, a Turkic people of Central Asia, took over and established settlements along the way (0.4). Two trade routes were most traversed. One passed through the land from the hilly areas of Gilan to Alburz that came to an end at the Caspian Sea. The Hindu Kush and the Pamirs cut off Inner Asia from India and the Tibetan Plateau. The route went by way of Khurasan and Kabul and entered the Indian subcontinent. The third turned south from Samarkand and went through Bactria toward Gandhara, which is now part of Afghanistan and Pakistan. By land and sea the Silk Route linked Tamluk on the Bay of Bengal. As a thriving cult center it introduced exotic votive terracotta that glorified the goddess wrapped in splendid gold and diaphenous silk (0.5).

Far from being a monolithic entity like Egypt, China did not have nationalistic lines either in geographical or cultural terms. Chinese territory from the Yellow River to its western frontiers extended towards Afghanistan and north-eastward to the Karakoram Range and the Tian Shan Mountains, which encompass the Tarim Basin. From the Carpathians in the west, grasslands stretch north of the Black Sea across the Dnieper, Don, and Volga rivers eastward to the drainage of the Irtysh River north of Lake Balkash and on to the foothills of the Altai Mountains. The mountain barriers of Hindu Kush, Karakoram, Kuen Lun, and the Western Himalayas did not prevent the merchants and religious zealots in their activities. South of the Kazakh Steppe is the extremely arid Turkistan and its Takla Makan Desert. The far-flung region's survival centered on natural oases on the caravan routes along Samarkand (Marakanda), Bukhara, Khiva, Merv, Kokand, Kashi (Kashgar), Yarkand, and Turpan (Turfan). The Silk Route went through ancient cities in which Chang'an, Dunhuang, Kashgar, Yarkand, Khotan, Herat, and Almaty linked East and West. The relatively safe overland routes under the Mongols from the Black Sea to the Pacific Ocean were used later by the Polo Brothers.

Sericulture and Han Silk

Out of the range of craft material the magical silk fabric is probably the most distinctively Chinese. Silk wearing requiring specialized skills, equipment, and process increased its prestige; pure kanaus silk is still called podshoki, the "Emperor's Cloth" in Central Asia. Silk was a major economic factor and signifier of social status. This was nevertheless not so noteworthy compared to its demand as shroud and as grave goods since silk was perceived to be a unique material effecting metamorphoses. The lustrous stuff spun from the cocoons was believed to reward rebirth and eternal life. To be buried in a silken shroud was actually not beyond one's dream in Central Asia. The silk fragments, apart from its historic and artistic significance, provide information on ancestor worship in the funerary cult that is deep-seated in China. The Chinese believed that the dead ancestors continued to be part of the family and had their own need in afterlife. The dead were thus cared for and propitiated with burial goods in which silk was a vital component. From Han dynasty (206 BCE-ca 220) onwards silk was currency for immortality. As Late as Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) period, a kind of furnace (kabala) was erected in the royal tombs near Beijing to burn messages on silk to communicate with the emperor's soul. With regard to veneration of ancestors, Matteo Ricci, who worked in China from 1582 until his death in 1610, wrote in his memoir:

The most solemn thing among the literati and in use from the exalted king down to the very least person is the annual offering they make to the dead at certain times of the year — of meat, fruit, perfumes, incense and pieces of silk cloth — and paper among the poorest. And in this act they make the fulfilment of their duty to their relatives, namely, "to serve them in death as though they were alive".[1]

A brief description by Phan shows that despite its ancient origins veneration of ancestors continued to be the most important ritual in China. In funerary rituals a piece of paper or white cloth bearing the name of the deceased is placed in front of the corpse prepared for burial. After burial, this name tag is brought home to the family altar to receive prayers and acts of piety. Eventually it is replaced by a piece of wood called the "spirit tablet". On its front the name, family status, and societal rank of the deceased are written, and on its back, the dates of birth and death. Since the soul of the deceased is believed to reside in this tablet, characters such as shen wei or Iing wei or shen zur meaning "the seat of the spirit" are inscribed on it. Venerated ancestors' portraits are placed in the family altar and on special occasions like birthday or death anniversary spirit of the dead is given offerings. On festivals such as the New Year and on the first and fifteenth days of the month of the lunar calendar, graves are tended and family members gather to feast on sacrificial food and drink and pay respect, burn silk, incense and paper money. Days are set aside in the traditional Chinese calendar for these duties, the most important being the "clear and bright" (qing ming) full-moon day in early April. At the heart of all these ancestor rites is filial piety (hsiao), the most important virtue in Confucian ethics, by which a person lives out five relationships (wu lun) — ruler and subject, parent and child, husband and wife, older and younger siblings, and friends.

Silk in Pre-Han Eurasia

Ancient-most excavated Han textiles according to style and motif belong to Western Han (207 BCE - c. 9) and Western Han (10-221),[2] Because of its social and economic status the secrets of silk manufacture were guarded by strict regulations, with threat of torture and death to those who break the restrictions. At Augustus Censer's demise in 14 CE the exotic iridescent silk was banned in Rome and was hence hoarded like gold. Silk shrouds in burials are much more visible than silk currency in barter or payment to army officers. As such the secrets of silk recovered from burials hold the reality of what life was for countless generations of the dead. A unique culture emerged out of a distinctive historic setting. The search is to discover the favorable conditions to the development of Han silk industry and how the wide market for silk in Central Asian burials was linked to the escalation of the Greco-Buddhist relicary cull in South Asia.[3] The evidence, strangely enough, might lie in the birth of as new era filled with renewed hope in resurrection and afterlife.

.............................

{p. 98} been and is and will be; and no mortal has ever lifted my mantle" had universal concurrence.[39] Apart from being a valuable stuff, the worth of silk is further enhanced by its magical motifs. From an early date the winged griffin in textiles was developed to manifest the divine. The garment worn by the Sasanian king on the rock carvings of Taq-i-Bustan in Iran depicts winged Serimurvs (Simurgh) set in an overall pattern of small medallions enclosing, rosette with four petals to convey immortality (2.34a). The Senmury caftan depicted on the left wall of the Great Ivan is similar to the ninth-century silk caftan with embroidered senmurvs conserved in the Hermitage Museum. It is made up of Sasanian and Chinese silk pieces decorated with the fabled senmurv. Textile design displaying unity of form and content demonstrates skillful organization of motifs based on clearly understood agenda. The senmurv carved on the costume of a Sasanian king at Taq-i-Bustan in western Iran reveals its extraordinary breadth and geographical span (2.34b). Senmurv, the winged griffin in Sasanian art, is a dog-faced winged lion embossed in gold applique (2.34c). The popular motif within a circular border in a treasured parcel gilt silver plate of a Sasanian king is typical of the wide variety of contexts (2.34d).

Senmurv.svg, The Sassanian Royal Symbol and the Mythology of Pers

One of the remarkable Sasanid weft-faced silk twill woven with simurgh is the reliquary of Saint Len in Paris (2.35). A fragment of this fabric in compound weave is in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London (8579-1863). The weft-faced compound structure utilize single or paired warp sets with plain weave or twill binding systems. Some of them are excavated in Egypt, northern Caucasus, India and China. The senmurv is enclosed in interlocking pearl roundels with stylized floral motifs filling the interstices. The framed senmurv replicated in Sogdian silk is interconnected at the tangent points by a crescent within smaller pearl medallion. The peacock tail of the senmurv is intricately woven and its distinctive armband with svmbolic motif reflects a taste for opulent textiles that extended outward from the Mediterranean basin. The crescent on the Alexandrian copper coin of Augustus as symbol of redeeming goddess Isis—Demeter recurs in the woven textiles of seventh-eighth century CE. In seventh and eighth centuries its original function was reclaimed in sculptures carved on several funerary monuments in Iran (2.36), A similar wall panel from the same site in Chal Tarhan but in a better condition is in the British Museum (A ME 1973.7-25.3). The Persian griffin widely used in textiles and metalwork as emblem of Sasanian kingship appeared first as necromantic sign on Greco-Buddhist reliquary mounds (2.37). The

[p. 98] been and is and will be; and no mortal has ever lifted my mantle" had universal concurrence.[39] Apart from being a valuable stuff, the worth of silk is further enhanced by its magical motifs. From an early date the winged griffin in textiles was developed to manifest the divine. The garment worn by the Sasanian king on the rock carvings of Taq-i-Bustan in Iran depicts winged Serimurvs (Simurgh) set in an overall pattern of small medallions enclosing, rosette with four petals to convey immortality (2.34a). The Senmury caftan depicted on the left wall of the Great Ivan is similar to the ninth-century silk caftan with embroidered senmurvs conserved in the Hermitage Museum. It is made up of Sasanian and Chinese silk pieces decorated with the fabled senmurv. Textile design displaying unity of form and content demonstrates skillful organization of motifs based on clearly understood agenda. The senmurv carved on the costume of a Sasanian king at Taq-i-Bustan in western Iran reveals its extraordinary breadth and geographical span (2.34b). Senmurv, the winged griffin in Sasanian art, is a dog-faced winged lion embossed in gold applique (2.34c). The popular motif within a circular border in a treasured parcel gilt silver plate of a Sasanian king is typical of the wide varietyt of contexts (2.34d).

One of the remarkable Sasanid weft-faced silk twill woven with simurgh is the reliquary of Saint Len in Paris (2.35). A fragment of this fabric in compound weave is in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London (8579-1863). The weft-faced compound structure utilize single or paired warp sets with plain weave or twill binding systems. Some of them are excavated in Egypt, northern Caucasus, India and China. The senmurv is enclosed in interlocking pearl roundels with stylized floral motifs filling the interstices. The framed senmurv replicated in Sogdian silk is interconnected at the tangent points by a crescent within smaller pearl medallion. The peacock tail of the senmurv is intricately woven and its distinctive armband with svmbolic motif reflects a taste for opulent textiles that extended outward from the Mediterranean basin. The crescent on the Alexandrian copper coin of Augustus as symbol of redeeming goddess Isis—Demeter recurs in the woven textiles of seventh-eighth century CE. In seventh and eighth centuries its original function was reclaimed in sculptures carved on several funerary monuments in Iran (2.36), A similar wall panel from the same site in Chal Tarhan but in a better condition is in the British Museum (A ME 1973.7-25.3). The Persian griffin widely used in textiles and metalwork as emblem of Sasanian kingship appeared first as necromantic sign on Greco-Buddhist reliquary mounds (2.37). The

...

[p. 248]. remains from the Parthian artifacts from Grave IV at Tillya Tepe in Afghanistan establish that embellishment of silk with gold thread was already in practice in the first century CE. The exquisitely crafted costumes and gold jewellery from the six graves in the "gold mound" were probably manufactured in Syria and Cyprus. The extraordinary geographical span of textiles originating in Central Asia has equally remarkable breadth of time. A fragment of Faimid-era door panel from Cairo depicts within a circular pearl roundel a celestial musician in a costume embellished with characteristic Sogdian circular motif within lattice framework (4.14).

Besides spreading cultural interchange, the "intercultural style" of silk continued to be a form of currency. Silk served as salary, reward, tax, and a means of barter and glorification until the medieval period. However, there was a marked reduction in the volume of trade due to the expansion of Islam when the explosive situation along the Silk Road stretched from Syria (636 CE), Alexandria (641 CE), and the whole of North Africa (647-98 CE). Islam held sway over commerce in the Red Sea and the Nile by capturing the caravan routes of North Africa, Spain (712 CE), and Persia. It introduced a gradual transition from Sasanian, Coptic, and Byzantine traditions in the form of highly valued Persian tiraz often inscribed with the names of kings, dates, and sites. Bestowed as sign of honor, fragments of many lines on tiraz used as shroud have been preserved in Egyptian tombs. These embroidered textiles provide window into political and religious life of early Islam. Bypassing the religious turmoil then besetting the West, China's trade during the Tang dynasty (618-906 ce) prospered due to the alternate East-West trade over the southern route by way of Ceylon and Tamil Nadu in south India. At the height of Tang dynasty, silk weaving in Kancipuram in Tamil Nadu flourished under the Pallava dynasty (fourth-late ninth century ce). Simultaneously, woodblock printing and dyeing workshops in South Asia produced less expensive substitutes for South-East Asia, Egypt, and West Africa. A group of seafaring Persians, Ethiopians, and Syrians traded in Chinese and Indian goods while the Chinese traded in lndo-China, Korea, India, and Ceylon from where her products reached Egypt, Eurasia, Persia, and the Byzantine Empire. Chinese raw silk was the most important single item of trade since the inception of the Roman Empire. Strategic geographic position of Persia enhanced trade with Syria and Byzantium that bought Chinese raw silk at inflated price till the fifth century. To maximize profit., the Soghdians in 550, like the Syrians of the Roman province, managed

Epilogue 249

to bypass both the Sasanian and Byzantine courts, and achieved great success in silk trade.[14] Their commercial interest was limited to the reselling of silk yarn and readymade raw silk from the Chinese to the merchants who supplied the Persians, Syrians, Byzantines, and Indians. The Sogdian cycle of mural paintings at Afrasiab in the so-called "hall of the ambassadors" represents not only their gorgeous silks and wealth but also their expectations in afterlife (2.22). The local ruler of Samarkand and Soghdiana, represented in the cycle of mural paintings, is identified as the governor (650-55 CE) sent by the Chinese emperor Gaozong (649-83 ce).[15] Efficient relay stations for the mounted messengers helped management of export and inter-regional trade. China imported from Syria precious and semi-precious stones and artificial glass gems. woven silk, wrought garments, and gold. Persia monopolized pearl and coral trade to China since these were important ingredients in Chinese magic potions and used as elixir of life in religious rituals. Iran's export to China also included wasma (woad —indigo) obtained from Egypt. In addition, the Persians sold enormous quantities of Persian brocades woven with Chinese yarn to meet the artificial demand created in Byzantium due to court restrictions. However, from mid-fifth to mid-sixth century CE Sasanian Iran suffered blockade by the Hephtalites rulers in Central Asia. The war with Byzantium for a century from 527 ce onwards was also a bleak period for the Sasanids (226-651 ce), when Turks made most of the embargo placed on Persian commodity by strengthening their hold on transit trade in silk combined with the traffic of dancing girls from Samarkand and Khotan. By taking control of the Silk Road the Turks benefited from direct trade with Byzantium and the Caspian regions. But these two vexing problems may ultimately be connected. One is the development of technology for its religious application in burial textiles and the recognition of the commercial advantage of the distribution of patterned silks in weft-faced compound weaves. Roger II of Sicily (1095-1154 CE), the nephew of Norman chief Guiscard, succeeded …

[14] Through the envoy led by Maniah the Sogdiarts at fiat sought free trade with Persia but it failed when Shah Khosro torched their silk in front of their eyes to prove that they had no need of the silk from the Sogdians or the Turks. The Sogdians were then encouraged by their Turkish rulers to negotiate directly with the Byzantines, the fiercest enemies of the Persians.

[15] Chavannes, Documenf Sur les Tou-kiue (Tyres) Occidentaux, SI. Petersburg, Ma 135. Quoted by Matteo Cornpareti, in Further Evidence for the interpretation of the 'Indian Scene' in the Pre-Islamic Paintings at Afrasiab (Samarkand).

ΒΙΒΛΙΟΓΡΑΦΙΑ

https://www.exoticindiaart.com/book/details/silk-road-fabrics-stein-collection-in-national-museum-of-india-nap935/?fbclid=IwAR2RffRovP-3WKTQT-JBpnSOVP91HLgQol8DaXFQFoTovWZSdkFdl09dTOQ

https://www.amazon.com/Silk-Road-New-History/dp/0190218428?asin=0195159314&revisionId=&format=4&depth=1

Sengupta, Arpurathani. 2018. The Silk Road Fabrics (The Stein Collection in the National Museum of India), New Delhi.

https://www.academia.edu/44851094/Textiles_of_the_Silk_Road_Enigmas_and_Riddlesdles_in_Cross_Cultural_Perspective_in_the_Art_of_Central_Asia

Sengupta, Arputharani. 2008. "Textiles of the Silk Road - Enigmas and Riddles," in Cross-Cultural Perspective in the Art of Central Asia, Aryan Books International, New Delhi, pp. 219-323.