Η ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ ΤΟΥ GILGAMESH

(ερανίσματα)

The Literary History of the Epic of Gilgameš[*]

Ανάγλυφο κεραμικό πλακίδιο με την πάλη του Γιλγαμές με τον 'ουράνιο ταύρο'[NOTE0]

INTRODUCTION

This book offers a new academic edition of the Babylonian text known today as the Epic of Gilgameš. It seeks to replace the long-obsolete edition of R. Campbell Thompson and the pioneering works of Paul Haupt and Peter Jensen which preceded that edition. In collecting between the covers of a single book every extant fragment of the Babylonian Gilgameš available at the time of writing, it aims to provide a definitive treatment that will place the study of the text on a sound footing until such time as future discoveries make another new edition necessary.

When applied to Gilgameš the term 'epic' is a coinage of convenience, for the word has no counterpart in the Akkadian language. By it is meant a long narrative poem describing heroic events that happen over a period of rime. The Babylonian Gilgameš fits this definition well. The poem tells the story of a great king, the hero Gilgameš, who so tyrannizes the people of the city of Uruk that the gods create his counterpart, the wild man Enkidu, to divert him. Enkidu is brought up by animals but seduced by a prostitute and civilized. Gilgameš and Enkidu fight, become inseparable companions and go together on a risky adventure to fell timber in the far Cedar Forest. On the way Gilgameš has a series of terrifying nightmares but nevertheless they slay the forest's guardian, the divinely appointed Humbaba, and fell the cedar. On their return Gilgameš repudiates the overtures of the goddess Ištar and, with Enkidu's help, despatches the monstrous Bull of Heaven that she sends to exact vengeance. For these twin misdemeanours the gods sentence Enkidu to death and he falls sick. He has a vision of the Nether world and dies, whereupon his friend is distraught with grief. After a magnificent funeral Gilgameš is consumed by the fear of death and sets off on a quest to the ends of the earth.The journey takes him where no mortal has been before, along the Path of the Sun and across the Waters of Death. He comes at last to the realm of the wise Uta-napišti, who survived the great flood sent by the gods in time immemorial and was granted immortality as a result. Under his instruction Gilgameš learns that there is no secret of everlasting life and is made to recognize his own human frailties, He returns home a wiser man and sets down his story for the benefit of future generations. [NEXT PAGE IS 4]

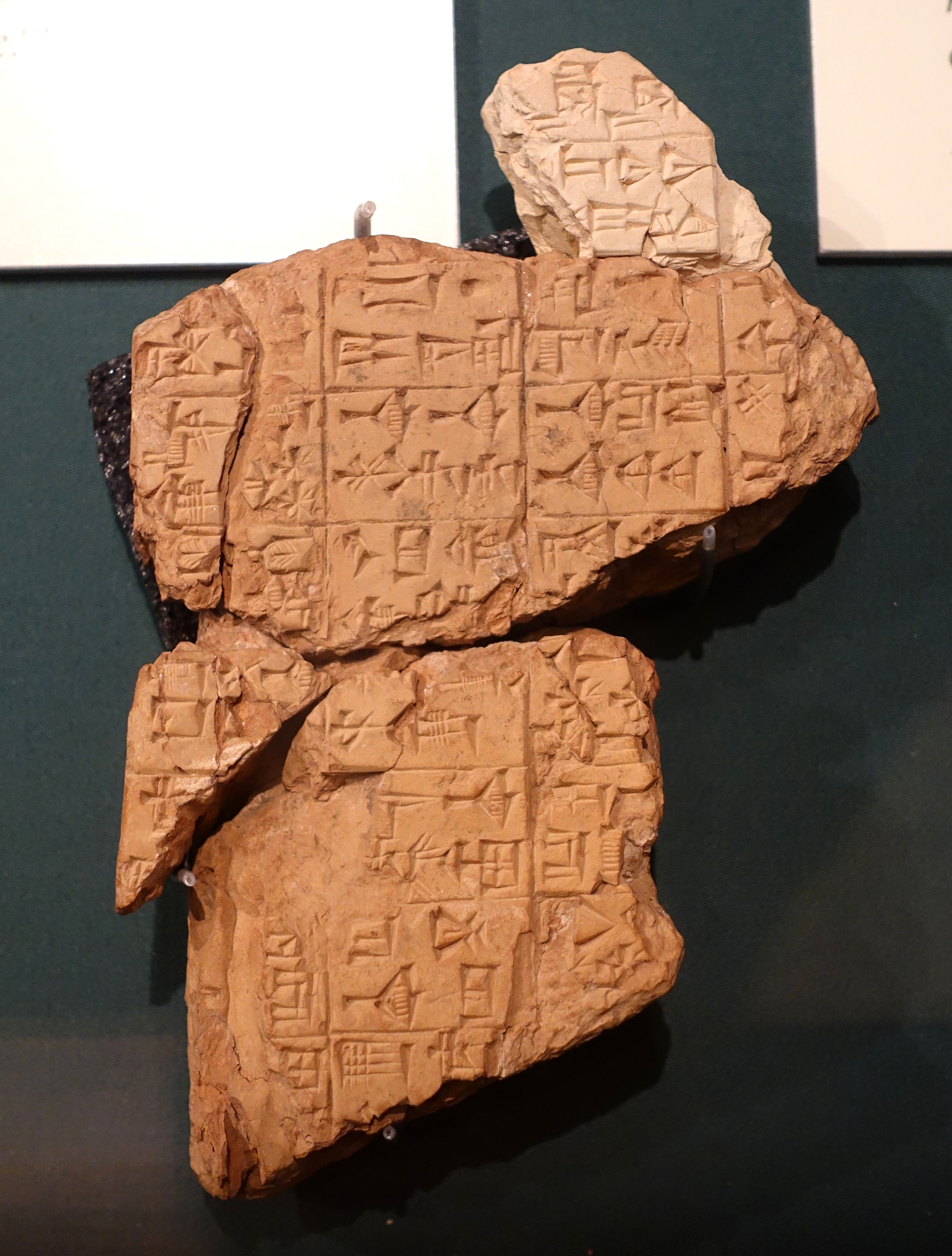

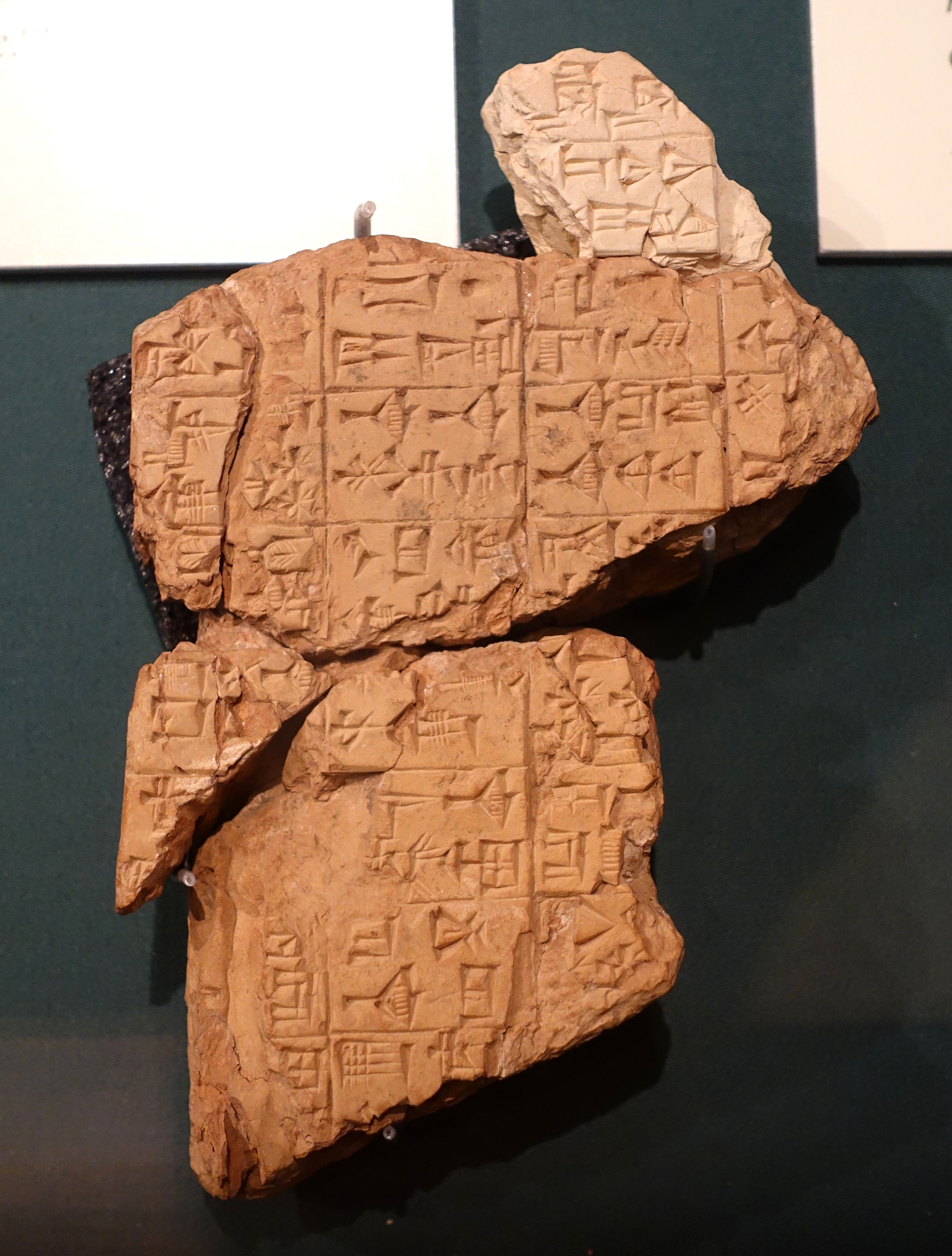

Νεοασσυριακή πήλινη πινακίδα με τον μύθο του κατακλυσμού[NOTE0A1]

The poem's climactic episodes make clear that it is more than just an exciting narrative of great deeds. Alongside the heroic feats lies a profound exploration of the limitations of the human condition.This, and the formal conceit of the epic, at least in its last version, that it comprises Gilgameš own words to those that come after, allows it to be read as a piece of `wisdom' literature with a message for posterity.[1] The poem's preoccupation with human experience and values and its jaundiced view of the authority of individual deities have prompted some to read it as a humanistic work, even the 'first embodiment in dramatic form and in explicit statement of the idea of humanism'.[2] Nevertheless the poem is not completely impervious to the religiosity of the culture from which it stemmed. In its recognition of man's ultimate powerlessness under the supreme authority of the divine the epic bows to the religious ideology of its time. As a piece of literature the epic leaps the divide between then and now, alone among the poetic narratives of ancient Mesopotamia, but it remains a distinctively Babylonian creation, nontheless.

The Babylonians referred to the poem by its opening words, 'Surpassing all other kings' (xxx), later 'He who saw the Deep' (xxx), and as the Series of Gilgameš (xxx). These titles, discussed more fully below, immediately reveal that the epic existed in at least two different versions. The truth is more complex than that, however. The story of Gilgameš has a long history in the ancient Mesopotamian literary traditions. Not only are there several different versions of the Babylonian epic in Akkadian, depending on time and place, but there are also related poems in Sumerian. Some nineteen centuries separate the oldest Sumerian fragment from the latest Babylonian manuscripts. Indeed, one can well say that the compositions telling the tale of the legendary king of Uruk offer between them a paradigm of ancient Mesopotarnian literature. This, the first of four introductory chapters, will place the various Gilgameš texts in the context of the historical development of the literature of Sumer and Babylonia.[3]

GILGAMES IN OLD SUMERIAN LITERATURE?

Θραύσμα των Instructions of Shuruppak (c. 2600 BCE — c. 2500 π.Χ.)[ΝΟΤΕ95]

The earliest recognizable body of literature recovered from ancient Mesopotamia is the Old Sumerian corpus of narrative compositions from the Early Dynastic IIIa period, roughly [NEXT PAGE IS 5] the mid-third millennium BC in the conventional chronology.[4]Texts of this archaic corpus can be properly understood only when later versions are extant. Thus manuscripts of the Instructions of Suruppak from Abu Salabilch and Adab and three copies of the Kes Temple Hymn from Abu Salabikh are largely comprehensible.[5] Texts known only from archaic versions, such as the collection of 'za-me-hymns', still present formidable problems of interpretation![6] This remains true when copies survive from different towns, as with the mythological texts from Abu Salabilth, Mari and Ebla—for example, the Sumerian composition in praise of Amausumgal[7] and an archaic Old Akkadian myth involving Šamas and other deities.[8] Three Sumerian texts from this archaic corpus have been claimed, at one time or another, as compositions involving Gilgameš. First, a mythological text from Abu Salabikh that describes the lovemaking of King Lugalbanda of Uruk and the goddess Ninsun has been supposed to relate the birth of Gilgameš.[9] Lugalbanda and Ninsun are well known in later Surnerian literary tradition as the parents of Gilgameš but the hero's name does not occur in the fragment. In the current state of knowledge the interpretation of any part of the text as referring to a birth involves a high degree of imagination and should be repudiated as unproven. The succession of legendary kings of Uruk— Enmerkar, Lugalbanda, Gilgameš —occupied a large proportion of the later corpus of poetic narrative in Sumerian, and the importance of this text for Gilgarneš studies is that it proves this dynasty was already a source of literary inspiration in the mid-third millennium.[10]

A second text is the composition in praise of Amausuumgal that was mentioned earlier as an example of archaic literature known from copies found at Abu Salabilch, Mari and Ebla. Before it was published the Ebla version of the test was claimed as a legend about Gilgameš and Aratta,[11] but a scholarly study of the two Ebla tablets found no reference to [NEXT PAGE IS 6] Gilgameš.[12] According to later tradition, Amaukungalanna signifies the ruler of Uruk in his role as Durnuzi, the husband of manna. Dumuzi is the subject of a large body of later Sumerian literature and it would be no surprise to find a text devoted to his praise in the Old Sumerian corpus. Nevertheless, the claim of association with Gilgameš persists, for the composition has recently been referred to as the 'Early Dynastic Hymn to Gilgameš. For my part I see little in the text, if anything, to support the statement of the commentator who coined this title that 'many allusions to episodes appearing in the later-attested Gilgameš cycle of legends do appear, and there can be little doubt that this composition as a whole glorified Gilgameš.[13]

Προ-Αχαιμενιδικό λεμβόσχημο αγγείο με αίγες και ιερά δένδρα[NOTE13A]

It is true that little of the text is readily intelligible, despite the fact that it is damaged only in its last sixth. However, the relatively complete state of preservation of the text immediately gives rise to a formal objection. Given that the Early Dynastic spelling of the name of Gilgameš is well known and immediately recognizable (see Chapter 2), an identification of this text as a hymn to Gilgameš rests on the unacceptable presumption that its composer omitted to identify by name the object of his adoration, unless he did so right at the end where the text is damaged. Perhaps in time detailed justification for this controversial interpretation will be put forward, but until then the text should be disregarded as far as the literary history of Gilgameš is concerned.

The third Old Sumerian tablet in question is not yet fully published and cannot be described definitively. Now in Norway as part of the Schoyen Collection, it has been provisionally identified by an anonymous cataloguer as an archaic manuscript of Gilgames and the Bull of Heaven.[14] Personal study of the piece did not lead to a specific identification but gave no grounds for agreeing with the cataloguer. The early rulers of Uruk had a great impact on poets of the third millennium, much as the Trojan war and its aftermath had on Homer. The reigns of Enmerkar, Lugalbanda and Gilgameš entered legend as the heroic age of Sumer. One can imagine that court minstrels and storytellers began to compose oral clays of ancient Uruk' soon after the lifetime of these heroes, and it would then be no surprise for epic tales of Gilgameš and his predecessors in due course to appear in writing. At the moment one cannot be sure that this happened in the Early Dynastic period, but it had certainly happened by the end of the millennium.

p. 56

system and find refuge in foreign parts—or could it? Two lines of enquiry need close examination. First is the relationship of the Homeric epics to the Epic of Gilgameš, second the legacy of the latter to the literatures of the post-cuneiform Near East. The question of ancient Near Eastern influence on the Iliad, Odyssey and other Greek literature has been the subject of considerable discussion; the relationship of Gilgameš to Homer began to be explored almost as soon as the contents of the Babylonian poem were presented in a reliable form.[138] The positions taken vary between the two extremes of (a) dismissal of any resemblance as coincidental and (b) claims of direct influence east to west. Recent writers have tended towards position (b).

Literary influence is seen, correctly, as one of many types of foreign influence felt by the archaic Greeks — material goods, technology (including writing), intellectual ideas and cultural trends, the import of all these from the East to Greece made for what has been termed an 'orientalizing revolution'.[139] The fullest analysis of literary influence is Martin West's exhaustive study of the legacy of eastern literatures to Greece, which includes a very detailed exposition of Gilgameš motifs in Homer and other similarities between the two bodies of material.[140] He adopts position (b), concluding that 'both the Iliad and Odyssey show, beyond all reasonable question, the influence of the Gilgamesh epic, and more especially the Standard Babylonian version[140a] of that poem, including the supposititious Tablet XII.[141]

In considering the date and route of transmission West has a specific suggestion, suspecting 'some sort of "hot line" from Assyrian court literature of the first quarter of the seventh cenrury'.[142] Part of his argument for such a 'hot line' rests on two points, (a) that Homer's poems were inspired by a 'version of the Gilgamesh epic similar to that current in seventh-century Nineveh, marked out by the addition of the incongruous Tablet XII', and (b) that Tablet XII was itself the direct inspiration for the Nekyia of the Odyssey, in which Odysseus encounters the shades of the dead. The first point is undermined by the probability that Tablet XII was appended to the poem much earlier than the seventh century, for, as already noted, it is now known from Babylonian manuscripts as well as Neo-Assyrian.The 'window of opportunity' was thus much larger than the first quarter of the seventh century. The second point must be tempered by the report of the dead shades that survives as a fragment of text in the body of the eleven-tablet epic, where it seems to have been the climax of Enkidu's dream of the Netherworld in Tablet VII. This equally could be supposed the [NEXT PAGE IS 56]

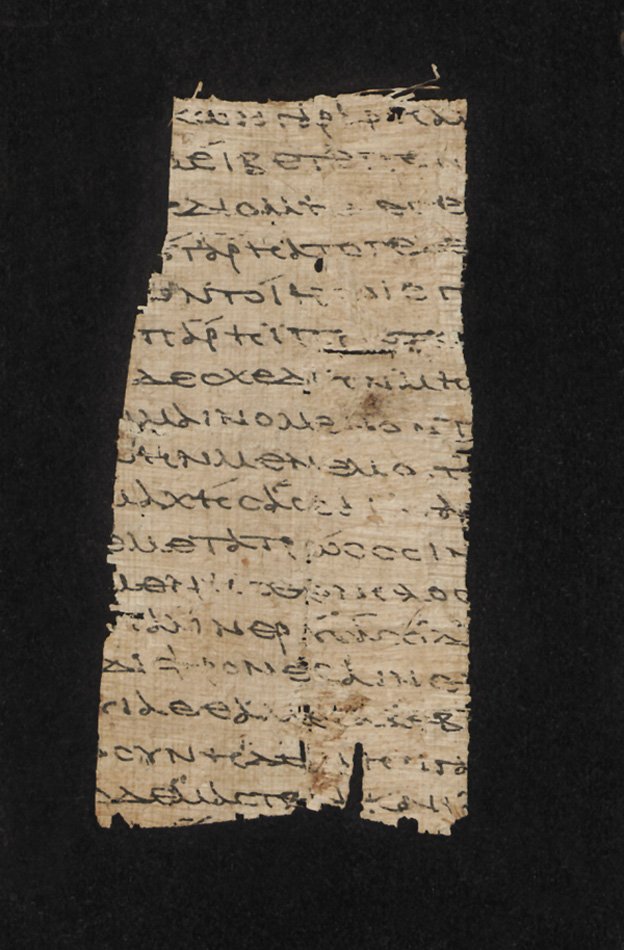

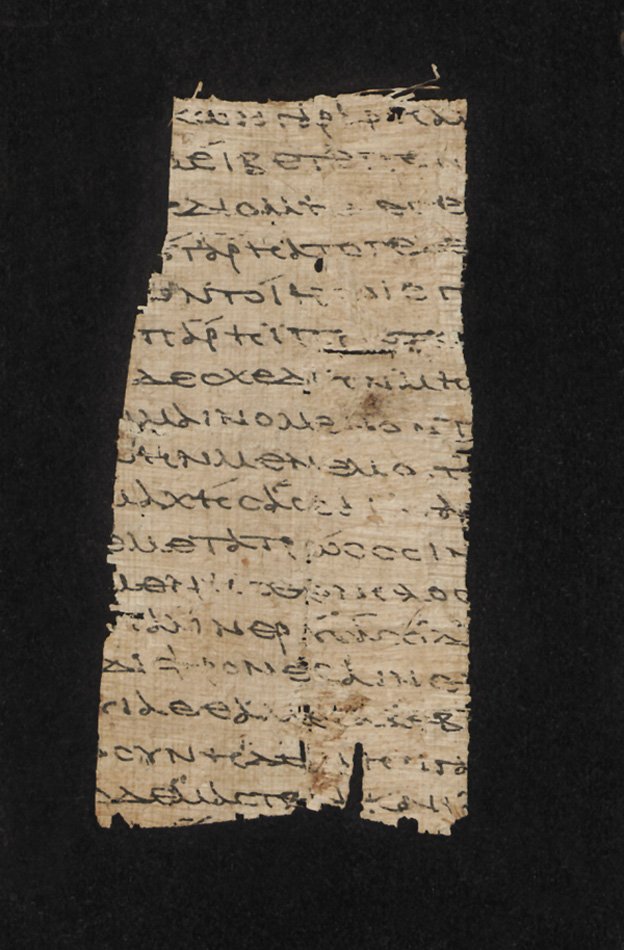

Πάπυρος με απόσπασμα της Ιλιάδος (2ος αι. Ms. 1063)[NOTEx]

p. 57 HOMER

The undeniable similarities between Homer and Gilgameš may accordingly not have arisen as a result of the influence of a contemporaneous version of the Babylonian epic (or a translated version) on archaic Greece, direct or indirect. More probably, Greek poetry imported from the eastern Mediterranean region motifs, episodes, imagery and modes of expression that were always traditional in the narrative poetry of the area or had been adopted into that poetry from Mesopotamia long before.[147] This position would best explain, for example, the currency of the 'fatal letter' motif in Sumerian literature of the eighteenth century BC (where the intended victim is Sargon), and its presence after a thousand-year interval in the biblical book of Samuel (Uriah) and the Iliad (Bellerophon).[148] Seen against such a pattern, Homer's tale of the adventures of Odysseus, so reminiscent of the Wanderings of Gilgameš his story of Achilles and Patroclus as two friends separated by death, so suggestive of Gilgameš and Enkidu, and Odysseus's interview with his dead mother and other shades, so similar to Enkidu's reports of the Netherworld---ancestral versions of all these, whether deriving ultimately from Mesopotamia or not, may have been present in Levantine poetry long before the time of the archaic Greeks. Similarly, shared imagery, such as when Gilgameš and Achilles are both compared in their grief to lions bereft of their cubs, can be explained as dependence on traditional forms. For this reason while I acknowledge the many parallels between Gilgameš and Homer, I see the poems as much more distant relatives than do those who argue for direct influence.

The second matter that calls for comment is the question of whether the Epic of Gilgameš survived the death of cuneiform writing in Mesopotarnia. It may be useful to pause here briefly to examine the evidence for general cultural continuity in the post-cuneiform age and then to consider the literature of Mesopotamia in the immediately preceding period. Here, too, there has been a good deal of recent research. With regard to the survival of Babylonian culture, what one finds is that in the early cenruries AD there was considerable continuity in religion and in the traditional sciences' rooted in the old cuneiform learning.

p. 67 HOMER

p. 144 HUMBABA

p. 443: CONCLUDING REMARKS

The epic presented in Chapter 11 is essentially a modern construct built from ancient evidence, not the authentic text of the Standard Babylonian epic at one single moment in its transmission.[43] Given the fragmentary nature of the sources, their paucity, and their different provenances and dates, it would be unrealistic to make any claim of true authenticity, and until the unlikely day when a complete set of twelve undamaged tablets becomes available, it always will be.

Γιά τα Ομηρικά έπη..[NOTE150]

..

Η μελέτη των ομηρικών ποιημάτων αποτελεί αναμφίβολα ένα προνομιακό θέμα της Κλασικής Φιλοσοφίας ενώ το λεγόμενο Ομηρικό ζήτημα, που έθεσαν με τον δικό τους τρόπο οι Αλεξανδρινοί μελετητές και διατυπώθηκε ρητά τον 19ο αιώνα, εξακολουθεί να απασχολεί μέχρι σήμερα, προκαλώντας διαφορετικές προσεγγίσεις. Γιά να πειστεί κανείς αρκεί να κοιτάξει τις σχετικές σελίδες σε οποιονδήποτε από τους τόμους του περιοδικού Année Philologique. Μέχρι σχετικά πρόσφατα, ωστόσο, το πρόβλημα παρέμενε έξω από τις ανησυχίες των ιστορικών. Για αυτούς, αρκούσε να χρησιμοποιήσουν τα ποιήματα ως ιστορική πηγή, να τα συγκρίνουν με στοιχεία από την αρχαιολογία και, αργότερα, από τις μυκηναϊκές πινακίδες και, στην καλύτερη περίπτωση, λαμβάνοντας υπόψη την εγκυρότητα της χρήσεώς τους για την γνώση της εποχής στην οποία φαινόταν να αναφέρονται. Ευτυχώς, οι προοπτικές έχουν αλλάξει και σε αυτό σημαντικό ρόλο έπαιξαν οι γνωστές θεωρίες του Finley για «τον κόσμο του Οδυσσέα», το θέμα ενός βιβλίου που εκδόθηκε για πρώτη φορά το 1954 και διανεμήθηκε ευρέως με μεταφράσεις σε όλες τις σύγχρονες γλώσσες.

Τώρα, το πρόβλημα έγκειται στο πώς μπορεί να αποτυπωθεί η ιστορία μέσα από ένα λογοτεχνικό είδος στο οποίο είναι αδύνατο να διαχωριστεί ξεκάθαρα τι, από την άποψη των οριστικών συντακτών ή συγγραφέων του, είναι μέρος του παρόντος και τί αυτό που ανήκει, για τους ίδιους, σε ένα μακρινό παρελθόν. Το ότι το έπος ως αρχικώς προφορικό είδος έχει υποστεί μια σειρά μετασχηματισμών με την πάροδο του χρόνου σύμφωνα με την ιστορική εξέλιξη, είναι κάτι που είναι ευρύτερα αποδεκτό. Προκειμένου να εμβαθύνουμε στους μηχανισμούς με τους οποίους λειτουργούν τέτοιοι μετασχηματισμοί, είναι απαραίτητη η στενή συνεργασία μεταξύ ιστορικών μελετών και της λογοτεχνικής και γλωσσικής αναλύσεως των ποιημάτων στην οριστική τους μορφή. Πρέπει να αναγνωριστεί ότι, μέχρι τώρα, η συνεισφορά από αυτούς τους τελευταίους κλάδους είναι πολύ πιο πλούσια από αυτήν των ιστορικών, ίσως επειδή, ως ένα βαθμό, συνεχίζουν να αναζητούν μια πραγματικότητα, είτε αυτή αντιστοιχεί στον όγδοο αιώνα είτε σε κάποια από τις προηγούμενες στιγμές μέχρι να έλθει το τέλος του μυκηναϊκού κόσμου.

Ο A. Aloni ξεκινά από το πεδίο της ιστορίας της λογοτεχνίας, αλλά και από την κατανόηση ότι το λογοτεχνικό φαινόμενο είναι ιστορικά προσδιορισμένο. Για αυτό, γνωρίζει ότι η χρονολογική θέση καθενός από τα αναφερόμενα δεδομένα έχει μικρότερη σημασία από τις διάφορες προσαρμογές που έχουν πραγματοποιηθεί σε αυτά μέσω λεπτών και ασυνείδητων χειρισμών, που τείνουν να προσαρμόζονται σε νέα ακροατήρια, σε ιστορικές συνθήκες που διαρκώς ανανεώνονται. Ο μύθος, θεμελιώδης πυρήνας του επικού είδους, διαθέτει, μεταξύ των πολλαπλών λειτουργιών του, πολλές «αληθειες» σύμφωνα με τις διαφορετικές αναγνώσεις που γίνονται σε αυτό, αυτήν της νομιμοποιήσεως της παρούσας πραγματικότητας, του άμεσου παρελθόντος και των μελλοντικών έργων, χάρη στη στήριξη σε ένα μακρινό και με κύρος παρελθόν.

Προβλήματα όπως «ο ποιητής και το κοινό του» και η κοινωνική λειτουργία της λογοτεχνίας είναι, από εδώ, βαθιά ριζωμένα στις ανησυχίες του ιστορικού που προσπαθεί να κατανοήσει την μή γραμμική σχέση, μεταξύ πηγής και πραγματικότητας.

Οι σχέσεις λογοτεχνίας και ιστορίας πρέπει να μελετηθούν και προς τις δύο κατευθύνσεις & συμπληρωματικά.

Το βιβλίο του A. Aloni παρουσιάζει μια σειρά σύνθετων επιχειρημάτων, όπου παρεμβαίνουν πολλαπλοί διαφορετικοί και ενίοτε αντιφατικοί παράγοντες. Ο συγγραφέας μας οδηγεί σε ένα μονοπάτι που, παρά την πολυπλοκότητά του, είναι άνετο, χάρη στο τέλειο πλαίσιο των επιχειρημάτων και την συνοχή του, έτσι ώστε να διαμορφώνεται ένα είδος «ίντριγκας» μέχρι να καταλήξουμε στα γενικά συμπεράσματα. Η συνοχή όλων των διαλεκτικών στοιχείων που απαρτίζουν τον συλλογισμό εμποδίζει κάθε είδους αφηρημένη ή μή σύνθεση. Ακόμα κι έτσι, με τον κίνδυνο να πέσουμε σε παραμορφωτικό σχηματισμό, δεν πρόκειται να εγκαταλείψουμε την προσπάθεια.

O A. Aloni πιστεύει στην θεωρία που υπερασπίζεται ότι, στην οριστική επεξεργασία των ποιημάτων, σημαντικό ρόλο έπαιξε η Πεισιστρατιδική επιμέλεια, η οποία εκτιμάται ότι θα λάμβανε υπόψη, κυρίως, την ιωνική εκδοχή. Μια τέτοια διατύπωση, όμως, επιφέρει μια σειρά χειρισμών και συγκαλύψεων που επηρεάζουν κυρίως την μορφή του Θησέως, που σχετίζονται με τις αθηναϊκές αριστοκρατικές οικογένειες οι οποίες υπήρξαν αντίπαλοι του τυράννου. Υπήρχαν μάλιστα και άλλες παραδόσεις, στις οποίες κυριαρχεί ο ρόλος του Θησέως και των συγγενών του και γίνονται γνωστές μέσα από διακοσμημένα κεραμεικά και θέματα τραγωδίας, εν προκειμένω διαμορφώνοντας ως ιδρυτή της δημοκρατίας και της αθηναϊκής εξουσίας.

Η συνδετική γέφυρα με την Μικρά Ασία βρίσκεται ακριβώς στο Σίγειον [αρχαία ελληνική πόλη της βορειοδυτικής Τρωάδας, στις εκβολές του Σκαμάνδρου ποταμού], ευρισκόμενο υπό τον έλεγχο των Πεισιστρατιδών, αλλά και σημείο εκκινήσεως των αθηναϊκών βλέψεων εντός της Τρωάδας, των οποίων η νομιμότητα βρισκόταν στις παραδόσεις που αναφέρονται στην Οικογένεια των Θησειδών [NOTEab]. Τα ονόματα αυτών, όμως, βρίσκονται στο έπος, συνδεδεμένα με τους Τρώες, σε μια εποχή βέβαια που δεν έχει δημιουργηθεί η ταύτιση αυτών με τους βαρβάρους, προερχόμενα από τους κινδύνους που εμφανίστηκαν με τον περσικό επεκτατισμό. Οι Δαρδανίδες είναι ακριβώς οι πρωταγωνιστές της επικής εκδοχής που μπορεί να ανιχνευθεί ανάμεσα στους Λέσβιους, φορείς της χαμένης αιολικής παραδόσεως.

Ο Αινείας και οι απόγονοί του, όπως και οι Θησείδες, παίζουν έναν αντιφατικό και παραμορφωμένο ρόλο, αντανακλώντας την προηγούμενη παράδοση που είχε περιοριστεί στην οριστική εκδοχή. Οι Αιολείς και οι Αθηναίοι διατηρούν μάλλον συγκρουσιακές σχέσεις γειτονίας στην Τρωάδα, οι οποίες αντανακλώνται στη δυναμική των επιρροών και απορρίψεις που προσφέρουν τα αντίστοιχα θέματα στα ποιήματα. Η λεσβιακή λυρική ποίηση, καθώς και τα θραύσματα της αρχαϊκής ιστοριογραφίας, πολύ κοντά στον μύθο και το έπος, συγκεντρώνουν τα απομεινάρια μιας επικής παραδόσεως αιολικής καταγωγής.

Η ιστορική πραγματικότητα δεν επιτρέπει σχηματισμούς και, ως εκ τούτου, ο συγγραφέας τονίζει ότι, παρά την ανίχνευση δύο διαφορετικών παραδόσεων, υπάρχουν συνεχείς επιρροές μεταξύ τους, σε σημείο που δεν είναι δυνατή η οριστική απομόνωση των στοιχείων. Η λογοτεχνική, τυπογραφική και γλωσσική ανάλυση μας επιτρέπει να συσχετίσουμε την ποικιλομορφία του λογοτεχνικού γεγονότος με την ιστορική πραγματικότητα. Από την άλλη, η μελέτη των ιστορικών συνθηκών μας επιτρέπει να καταλήξουμε σε θεμελιώδη συμπεράσματα για να ξεπεράσουμε τη διαμάχη ενωτικών[NOTEa] και αναλυτικών [NOTEb] αναφορικά με το πρόβλημα της συνθέσεως των ομηρικών ποιημάτων.[NOTEc] Σε μια εξέλιξη στην οποία έχουν παρέμβει τόσα πολλά και ποικίλα στοιχεία, η καθήλωση σε μια δεδομένη στιγμή μιας ζωντανής παραδόσεως δεν κάνει τίποτα περισσότερο από το να παραλύει την ιστορική διαδικασία σε ένα ορισμένο σημείο, όπου η καινοτομία και η παράδοση αναμειγνύονται άρρηκτα μα παίζουν διαφορετικούς ρόλους, με μιαν ελευθερία της οποίας τα μόνα όρια βρίσκονται στους κανόνες της μετρικής και της φόρμουλας [στερεότυπων εκφράσεων] και στην αξιοπιστία για ένα ενδιαφερόμενο κοινό, περισσότερο από ό,τι με το ίδιο το παρελθόν, με τον ρόλο που μπορεί να παίξει το παρελθόν ως νομιμοποιητής του παρόντος του και ικανοποιώντας την δική του ατομικότητα ενσωματωμένη στην κοινότητα.

Η ποικιλόμορφη πραγματικότητα της αρχαϊκής Ελλάδας επέτρεψε έναν απεριόριστο πλούτο στην ερμηνεία των δικών της παραδόσεων. Η 'σταθεροποίηση' του κειμένου [σταθερό ενιαίο κείμενο / αρχέτυπο] των ποιημάτων σήμαινε μια 'σκληροποίηση', αλλά οι παραδόσεις άντεξαν σε πολλαπλές πολιτιστικές εκδηλώσεις και τα ίδια τα ποιήματα αντανακλούν έναν πλούτο μέχρι τη στιγμή της σταθεροποιήσεως του κειμένου τους.

Εν ολίγοις, το γεγονός ότι η «σημερινή» πραγματικότητα έχει επηρεάσει την οριστική διαμόρφωση των ποιημάτων δεν τα ακυρώνει ως ιστορική πηγή, αλλά μάλλον γίνονται, από αυτήν την άποψη, η πηγή μιας πιο ποικίλης πραγματικότητας και διευρύνουν το πεδίο των ποιημάτων τους ...

Καταληκτικά Σχόλια

Ο George παρέχει την ακόλουθη σύντομη περιγραφή του Gilgameš:[NOTE160]

Το όνομα 'Έπος του Gilgameš' δόθηκε στο βαβυλωνιακό ποίημα που αφηγείται τα κατορθώματα του Gilgameš, του μεγαλύτερου βασιλιά και του ισχυρότερου ήρωα του αρχαίου θρύλου της Μεσοποταμίας. Το ποίημα εμπίπτει στην κατηγορία τού έπους επειδή είναι ένα μακροσκελές αφηγηματικό έργο ηρωικού περιεχομένου και έχει τη σοβαρότητα και το πάθος που μερικές φορές έχουν θεωρηθεί ως χαρακτηριστικά του έπους. Μερικοί πρώιμοι Ασσυριολόγοι, όταν ο εθνικισμός ήταν μια ισχυρή πολιτική δύναμη, τον χαρακτήρισαν ως το 'εθνικό έπος' της Βαβυλωνίας, αλλά αυτή η θεώρηση έχει πλέον ορθώς καταργηθεί.

Το θέμα του ποιήματος δεν είναι η ίδρυση ενός βαβυλωνιακού έθνους, ούτε ένα επεισόδιο στην ιστορία αυτού του έθνους, αλλά η μάταιη αναζήτηση ενός ανθρώπου να ξεφύγει από τη θνητότητά του. Στην τελική και καλύτερα διατηρημένη εκδοχή του είναι ένας σκοτεινός διαλογισμός για την ανθρώπινη κατάσταση. Τα ένδοξα κατορθώματα που αφηγείται υποκινούνται από μεμονωμένες ανθρώπινες δυσκολίες, ιδιαίτερα από την επιθυμία για φήμη και τη φρίκη του θανάτου.

Οι συναισθηματικοί αγώνες που σχετίζονται με την ιστορία του Gilgameš δεν αφορούν καμία συλλογική ομάδα αλλά το άτομο. Μεταξύ των διαχρονικών θεμάτων του είναι η τριβή μεταξύ φύσεως και πολιτισμού, η φιλία μεταξύ των ανθρώπων, η θέση στο σύμπαν των θεών, των βασιλέων και των θνητών και η κατάχρηση εξουσίας. Το ποίημα μιλάει για τις αγωνίες και την εμπειρία ζωής ενός ανθρώπου, και γι' αυτό οι σύγχρονοι αναγνώστες το βρίσκουν τόσο βαθύ όσο και διαρκώς επίκαιρο.

Ο ίδιος μελετητής διαχωρίζει τις πηγές των κειμένων του Gilgameš σε τέσσερις περιόδους και αντιμετωπίζει τις εκδοχές κάθε περιόδου ως ξεχωριστά στάδια εξελίξεως του ποιήματος, δείχνοντας ότι δεν υπάρχει ένα μόνον Έπος του Gilgameš, σημειώνοντας ότι σήμερα διασώζονται τμήματα διαφορετικών εκδοχών του που προέρχονται από μιά περίοδο 1800 ετών![NOTE162]

Τα παλαιότερα Σουμεριακά ποιήματα, πιθανώς χρονολογούμενα περί το 2000 π.Χ., αναφέρουν μερικούς από τους ίδιους θρύλους και θέματα με αυτά του παλαιο - βαβυλωνιακού ποιήματος, αλλά είναι ανεξάρτητες συνθέσεις και δεν αποτελούν ένα λογοτεχνικό σύνολο. Τα Σουμεριακά και Βαβυλωνιακά ποιήματα μοιράζονταν κάτι περισσότερο από μια κοινή λογοτεχνική κληρονομιά, είτε αυτή ήταν προφορική (όπως φαίνεται πιθανό) είτε γραπτή.[NOTE164] Συνολικά, αυτά τα έντεκα παλαιο - βαβυλωνιακά γραπτά παρέχουν αρκετά ασύνδετα επεισόδια σε λίγο περισσότερες από εξακόσιες ποιητικές γραμμές, όταν τα Ομηρικά έπη αριθμούν 12 και 15 χιλιάδες στίχους, η δε Mahabharata πολύ περισσότερους!

Το λεγόμενο έπος του Gilgameš θεωρείται πρώιμο έργο του Βαβυλωνιακού πολιτισμού, υπέρ του οποίου έχει δημιουργηθεί ισχυρό ρεύμα υποστηρίζον μάλιστα την εξ ανατολών έλευση του πολιτισμού (ex oriente lux). Πράγματι εκτιμάται ότι η Μεσοποταμία εισήλθε στην πρώτη πλήρως ανεπτυγμένη φάση αστικοποιήσεως κατά την αρχαϊκή IVa, περί το 3300 π.Χ., την ίδια δε εποχή είδε την εμφάνιση της πρωτο-γραφής..[NOTE165] Πάντως αυτό το σύστημα γραφής δεν επεκτάθηκε για να αποδώσει την προφορική γλώσσα παρά μόνον από τα μέσα της 3ης χιλιετίας π.Χ. περίπου.[NOTE165a]

Ο Παν – Βαβυλωνιασμός απετέλεσε σχολή στα πλαίσια της Ασσυριολογίας και των θρησκευτικών σπουδών η οποία θεωρεί την Εβραϊκή Βίβλο και τον Ιουδαϊσμό ως προερχόμενα από τον Βαβυλωνιακό πολιτισμό και μυθολογία, στο κλίμα δε του ίδιου ρεύματος κινείται και ο S. Parpola.[NOTE166]. Είναι χαρακτηριστικό εν προκειμένω ότι ο μελετητής Paul Haupt δημοσίευσε το κείμενο του Gilgamesh΄σε σφηνοειδή, το οποίο ονόμασε το βαβυλωνιακό 'Έπος του Nimrod'. Ο τίτλος ήταν μια αναφορά στον μεγάλο κυνηγό της Βίβλου, που πολλοί υποθέτουν ότι βασιζόταν στον Βαβυλωνιακό ήρωα![NOTE168]

Στο ίδιο μήκος κύματος υπερβολής ο Ιωσήφ Blenkinsopp, θεολόγος και μελετητής της Παλαιάς Διαθήκης, θα διατυπώσει την υπερβολική άποψη ότι η συγγραφική παράδοση [της Μεσοποταμίας] έθεσε τις βάσεις για την δυτική ιστοριογραφία, με τους άμεσους προγόνους της στο Ισραήλ και τους πρώτους χριστιανούς συγγραφείς!![NOTE169] Ενδιαφέρουσα πάντως η παρατήρηση του θεολόγου Βαβυλωνιαστή για την υιοθέτηση (και) της γραφής ως οργάνου καταπιέσεως και ελέγχου, ενώ ανάλογη είναι η θεώρηση του Nagy, αυτήν την φορά όμως εν σχέσει με τους Πεισιστρατίδες![NOTE169a]

Σύμφωνα με τον George, τα Ομηρικά έπη και το Έπος του Gilgamesh είναι μάλλον μακρινοί συγγενείς, οι ομοιότητες οφείλονται στο επικό είδος και τα μοτίβα, και στις εικόνες που εισάγονται στην Ελλάδα από την Ανατολή, και όχι σε άμεσες επιρροές.[NOTE170]

ΣΗΜΕΙΩΣΕΙΣ

* George 2001.

[NOTE0]. Χρονολογούμενο κατά την περίοδο βασιλείας του Naram-Sin (περ. 2250-1900 π.Χ.). Αλλά θα μπορούσε επίσης να παριστάνει τον lakmu ('ο σγουρός'), ακκαδικό Θεό των υπόγειων ποταμών που συχνά αντιπροσωπεύεται δίπλα στον άνδρα ταύρο, τον Kusarikku. Βρυξέλλες, Royal Museums of Art and history. O.1054color.jpg <https://el.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/%CE%91%CF%81%CF%87%CE%B5%CE%AF%CE%BF:O.1054_color.jpg>

[NOTE0A1]. British Museum K.3375, <https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_K-3375>.

[1] See already George, Epic Of Gilgamesh (Penguin), pp. xxxv-xxxvii. Note also G. Buccellati. 'Wisdom and not: the tale of Mesopotamia', JAOS 101 (1981), pp. 35-47, where the epic is adduced as one of several examples of Babylonian 'wisdom'; cf. especially p. 38: 'Gilgamesh (in its later version) is the great paradigm of this type of inner adventure i.e. the acquisition of knowledge through humility], a fact that has largely gone unnoticed because of the outter "epical" garb.

[2]. Gresseth 1975, p. 15; Moran 1991.

[3]. An earlier and much briefer attempt to do this is W. G. Lambert' essay `Zum Forschungsstand der surnerisch-babyonischen Literatur-Geschicke, ZDMG Suppl. 3 (1975), pp. 65-9 though overtaken by the discoveries of recent years it remains a valuable account. The longer treatment by J. H. Tigay, The Evolution of Gilgamesh Epic (Philadelphia, 1982), is marred by a tendency to see the various second-millennium fragments of the epic as standing in a single lineal deseenr. Newly discovered sources have made it ever more clear that the second millenium was characterized by a profusion of deviant texts.

[ΝΟΤΕ95]. Museum of the Oriental Institute, University of Chicago. Βλ. <https://www.historyofinformation.com/detail.php?id=1306> & <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Instructions_of_Shuruppak>.

[4]. A brief list of this literature is given by J. A. Black, 'Some structural features of Sumerian narrative poetry: Appendix A', Mesopotamian Epic Literature, p. 92; for an extensive description of the texts from Fara and Abu Salabikh see M. Krebernik, 'DieTexte aus Fara und Tell Abu salabih', in J. Bauer et a., Mesopotamien. Spaturuk-Zeir and Fruihkmastische Zeit (OBO 160/1; Freiburg and Gottingen, 1998), pp. 237-427.

[5]. For the former see B. Alster, The Instructions of Suzuppak (Copenhagen, 1974), pp. 11-25, for the latter, R. D. Biggs, 'An archaic version of the Kesh Temple Hymn from Tell Abe Salabikh', ZA 61 (1971), pp. 193-207.

[6]. R. D. Biggs, Inscriptions from Tell Abu Salabikh (OIP 99; Chicago, 1974), pp. 45-56; see further W. G. Lambert's review in BSOAS 39 (1976), pp. 428-32; M. Krebernik, 'Zur Einleining der za-me-Hymnen aus Tell Abe Salabily', in R Calmeyer et al. (eds.), Beitrage zur altarientalischen Archaologie und Akerturnskunde. Festschrift fiir Barthel Hrouda (Wiesbaden, 1994), pp. 151-7.

[7] Biggs, OIP 99 278 // D. O. Edzard, Hymnen, Besehwdrungen and Verwandtes aus dem Archiv L. 2769 (ARET V; Rome, 1984), nos. 20-1; a version from Mari is not yet published (TH 80.111, see Black, loc. cit.).

[8]. Biggs, OIP 99 326 (+) 3421/ Edzard, ARET V 6, on which see W. G, Lambert, 'Notes on a work of the most ancient Semitic literature', JCS 41 (1989), pp. 1-32; id., 'The language of ARET V 6 and 7', and M. Krebernik,'Mesopotamian myths at Ebla: ARET 5, 6 and ARET 5, 7', both in P Fronzaroli (ed.), Literature and Literary Language at Ebla (Quadema di semitistica IS; Florence, 1992), pp. 41-62 and 63-149.

[9]. OIP 99 327, last edited by T. Jacobsen, "Lugalbanda and Ninsurta", JCS 41 (1989), pp. 69-86; controversially reinterpreted by D. R. Frayne, "The birth of Gilgames in ancient Mesopotamian art", Bulletin CSMS 34 (1999), pp. 39-49.

[10]. See already B. Alster,"Lugalbanda and the early epic tradition in Mesopotamia', Studies Moran, p. 60.

[11]. G. Pettiziato, Cataogo dei testi atnelfarmi di Tell Mardikh-Ebla (MEE 1; Naples, 1979), nos. 2093-4; cf. id., Ebla. Un impero inciso nel' argilla (Milan, 1979), p. 257.

[12] See Edzard, ARET V, p. 39: 'Wahrend Aratta in der Tat vorkommt, finde ich keinen deutlichen Hinweise auf Gilgames. Protagonist ist, each rrihrfachern Vorkommen zu urteilen, sowic nach der Doxologie dAma-usum: Peninato's identification may have been based on a misreading of ARET V 21 v 2: GI (IRV GA NE as bill CGIS.NE). games, but the comments of J. D. Bing, 'Gilgamesh and Lugalbanda in the Fara period', ANES 9 (1977), p. 2, suggest otherwise.

[13]. Frayne, Bulettin CSMS, p. 39, where [ARET V] nos. 5 and 6' is a misprint for nos. 20 and 21.

[NOTE13A]. Hajime Inagaki 2019, pp. 56-57, cat. nr. 15. Παραθέτουμε το σχόλιο του επιμελητή του Μουσείου Miho:

ΈNA ΑΓΓΕΙΟ ΠΛΗΡΕΣ ΜΕ ΤΗΝ ΑΝΕΚΠΛΗΡΩΤΗ ΛΑΧΤΑΡΑ ΗΡΩΟΣ

Το βασικό σχήμα του αγγείου είναι αυτό μιάς ωοειδούς λέμβου με στρογγυλό κύτος. Υπάρχει μια λαβή στο ένα άκρο του ωοειδούς, ένα στόμιο στο άλλο. Ένας πόδας είναι στερεωμένος στο κέντρο του πυθμένα του σκάφους. Στο χείλος τοποθετείται μεταλλικό κάλυμμα με μεγάλη ορθογώνια οπή στο κέντρο. Εγχάρακτα και στις δύο πλευρές παριστάνονται τέσσερεις ιχθείς και δύο κόρακες.

Πρόκειται για νύξεις που παραπέμπουν στον μύθο του Μεγάλου Κατακλυσμού που εξιστορείται στο Μεσοποταμιακό ποίημα που ονομάζεται " Έπος του Γκιλγκαμές". Οι θεοί προκάλεσαν τον κατακλυσμό για να εξοντώσουν την ανθρωπότητα, αλλά ο θεός των υδάτων Εα (Ένκι) λυπήθηκε τον ευσεβή Utnapishtim και του είπε να φτιάξει τη βάρκα που τον έσωσε. Οι ιχθείς είναι σύμβολα των υδάτων του Ea, οι κόρακες είναι τα πτηνά που φέρνουν την είδηση ότι η πλημμύρα έχει υποχωρήσει. Σε Σουμεριακούς σφραγιδοκυλίνδρους από το δεύτερο ήμισυ της τρίτης χιλιετίας π.Χ. βρίσκουμε εικόνες του Ea, από τον οποίο αναβλύζουν ύδατα και ιχθείς, συνοδευόμενα από πτηνό. Ο Utnapishtim έλαβε την αθανασία από τους θεούς, οι οποίοι όμως την αρνήθηκαν στον ήρωα Gilgamesh, που την αναζήτησε αλλά δεν κατάφερε να περάσει τη δοκιμασία που απαιτείται για να την λάβει.

Υπάρχουν πολλές χρυσές εικόνες του μουφλόν, του ασιατικού άγριου προβάτου προσαρτημένου στο σκάφος. Οι τρεις χουρμαδιές που βρίσκονται ανάμεσα σε ζεύγη μουφλόν δείχνουν ότι αυτό το σκάφος είναι γεμάτο με την ζωτική δύναμη που απαιτείται για την αναγέννηση και την αφθονία. Ένα μουφλόν στέκεται στην πλώρη του σκάφους, στραμμένο ευθεία μπροστά. Το στόμιο είναι το μπροστινό μισό ενός άλλου μουφλόν, του οποίου το σώμα προεξέχει από την πλώρη. Μόνο ένα λιοντάρι, ως απλό ζώο φύλακας, στέκεται φρουρός στην λαβή στην πρύμνη.

Στον πνευματικό πολύ ζοφερό κόσμο της Μεσοποταμίας, απαισιόδοξες απόψεις διέπουν τόσον αυτόν τον κόσμο όσον και τον κόσμο μετά θάνατον. Οι Ιρανοί, που κατασκεύασαν αυτό το λεμβόσχημο αγγείο, είχαν πολύ διαφορετική οπτική. Κατά την άποψή τους, όσοι τηρούσαν τις υποσχέσεις τους στον Μίθρα, τον θεό που έλεγχε τον κόσμο, θα λάμβαναν την τεράστια προστασία του θεού. Αυτό το δοχείο φαίνεται να ενσαρκώνει αυτή την πίστη στον Μίθρα. Είναι γεμάτο ελπίδα που μόνο οι ευσεβείς μπορούσαν να μοιραστούν.

[14]. A colour photograph of the text, SC 2652/3, appears on the Schoyen Collection's website at http://www.nb.no/basertschoyen/4/4.3/431.html (ed. E. G. Seirenssen, as read in June 2001). The accompanying notes report: ‘MS in Old Sumerian on clay, ca 2600 BC, 1 tablet, 8.3 X 9.1 X 2.4 cm, 3 columns, 25 compartments in cuneiform script . This is the earliest tablet of Gilgarnesh, more than 600 years older than any other tablet known, written about 100 years after Gilgamesh died. Only 3 compartments have so far been read, seeming to be from Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven, one of the 5 tales that later merged to form the epic of Gilgamesh.The remaining 22 compartments need to be read to establish that the text really is Gilgamesh'.

[136]. P. Jensen followed up his pioneering edition of the whole extant epic with an article entitled 'Das Gilgamesh-Epos and Horner.Vorlaufige itteilung', ZA 16 (1902), pp. 125-34, with additional comments on pp. 413-14.

[139]. See esp.W. Burkert, The Orientalizing Revolution: Near Eastern Influence on Greek Culture in the Ear& Archaic Age (Cambridge, Mass., 1992).

[140]. M. L. West, The East Face of Helicon (Oxford, 1997); to the bibliography on Gilgameš and Homer assembled there (esp. p. 335, fn. 3) add T. Abusch, 'The Epic of Gilgarnesh and the Homeric epics', in R. M. Whiting (ed.), Mythology and Mythologies (Melammu Symposia 2; Helsinki, 2001), pp. 1-6. Abusch's paper makes presumptions about the historical development of the Gilgameš epic that are unjustified and then seeks a parallel development in the Odyssey.This latter development is supposed in some way to exhibit the influence of the former development, even though the Greek poem in its oldest form is much younger than the Babylonian poem in its latest.

[140a]. Η τυπική έκδοση του 'έπους' χρονολογείται από τον VII αι. π.Χ. (Asurbanibal library, 669-630 ΒC), ενώ η Ομηρική καταγραφή τοποθετείται στην ίδια ή παλαιότερη περίοδο! Όμως στις πινακίδες αναφέρεται το όνομα του Sîn-lēqi-unninni, ημι-μυθικού γραφέα στον οποίον αποδίδεται η 'επιμέλεια' της τελικής μορφής του 'έπους', χρονολογούμενη πιθανώς μεταξύ 1300 και 1000 π.Χ., βλ. <https://history.stackexchange.com/questions/48551/whats-the-dating-of-the-standard-akkadian-version-of-the-gilgamesh-epic>, επίσης: George 2001, pp. 28-33. Κατά τον George ανωτέρω ο Sîn-lēqi-unninni εθεωρείτο από τους kalû, ιερατικούς ψάλτες και λοιπούς διανοουμένους της ιερατικής τάξεως, της παλαιο - βαβυλωνιακής περιόδου, ως μακρυνός πρόγονός τους. Ο ισχυρισμός αυτός, όμως, πάντα κατά τον George αντλούσε την έμπνευσή του από πνευματική φιλοδοξία ή ευσεβή πόθο, παρά εδραζόταν στην αλήθεια (a claim that may hav been inspired by intellectual ambition or wishful thinking, rather than by truth) [George 2001, p. 29, n. 78]

Ο George τείνει να δεχθεί ότι ο Sîn-lēqi-unninni υπήρξε μάλλον επιμελητής του έργου κατά τα τέλη της δεύτερης χιλιετίας [George 2001, p. 30].

[141]. West, East Face of Helicon, p. 587.

[142]. Ibid., p. 627.

[146]. See further Ch. 10, the introduction to SB Tablet V.

[NOTEx]. Edgar J. Goodspeed Papyri Collection. Το συγκεκριμένο τμήμα παπύρου προέρχεται από την Αρσινοΐτιδα (Fayûm), πιό συγκεκριμένα από το Kûm Ushîm (Washîm), δηλαδή την Καρανίδα Αιγύπτου. Το κείμενο ανήκει στην ραψωδία 5 της Ιλιάδος, στ. 824-841. Βλ. <https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/collex/exhibits/homer-print-transmission-and-reception-homers-works/homer-print/>.

[147]. A similar point was made by N. Wasserman in his review of West, East Face of Helicon, in Script Classica Israelica 20 (2001), p. 262: `Another possible reading of the evidence could suggest a Mediterranean "Kuletabund" ... a cultural conglomerate shared by the various societies located around the Mediterranean basin: Abusch offers a similar escape route for the problem he made for himself (see above, fn. 140): 'perhaps the Homeric works and the Epic of Gilgamesh initially developed independently, though they may have drawn upon a common narrative tradition' (Mythology and Mythologies, p, 6). Lambert is more sure: it seems certain that Homer did not read Gilgamesh, nor Hesiod the Epic of Creation. Rather the literary works are products from intellectual cultures interrelated in more than one way. Common traditions going back to neolithic times may be suspected, while interaction both oral and written no doubt took place in some cases in historical times' (W. G. Lambert, Classical Review 41/I (1991), p. 114).

[148]. For brief details see B. Aster, 'A note on the Uriah letter in the Sumerian Sargon legend', ZA 77 (1957), pp. 169-73, and further literature there cited; cf.West, East-Face of Helicon, pp. 365-6.

NOTEab]. https://science.fandom.com/el/wiki/%CE%97%CE%B3%CE%B5%CE%BC%CF%8C%CE%BD%CE%B5%CF%82_%CE%9C%CF%85%CE%BA%CE%B7%CE%BD%CE%B1%CF%8A%CE%BA%CE%AE%CF%82_%CE%91%CE%B8%CE%AE%CE%BD%CE%B1%CF%82.

NOTEa. Καρακάντζα: ενν. Ενωτικοί: M. Parry & A. Lord: θεωρία της προφορικής ποιήσεως

NOTEb. Καρακάντζα: ενν. Θεωρία μικρών επών / συμπίλησης: μικρά προγενέστερα έπη -> ένας ποιητής «συγκόλλησε» τα έπη..

NOTEc. Καρακάντζα. Νεοανάλυση (Ι. Θ. Κακριδής, W. Kullmann): Προϋπάρχουν θεματικά μοτίβα & ο ποιητής τα συνθέτει διαφορετικά, παραδείγματα: Αιθιοπίδα, Πατρόκλεια (Π-Ρ), Θρήνος για τον Πάτροκλο (Σ), Άθλα επί Πατρόκλω (Ψ). Από την άλλη ο Cline (Cline 1997, p. 198, nn. 36, 37) σημειώνει: κατά τον Wolfgang Kullmann, η Νέα Ανάλυση (Neoanalysis) συνιστά

μια κριτική προσέγγιση της Ιλιάδας που θεωρεί τις ιστορίες και τα θέματα του επικού κύκλου ως πηγές ή ως φόντο για το ομηρικό ποίημα.

Με άλλα λόγια, ορισμένα τμήματα της Ιλιάδας μπορεί αρχικά να απετέλεσαν μέρος (ή είναι απομιμήσεις) άλλων επικών κύκλων που αφορούσαν γεγονότα από μια προ-Τρωϊκή εποχή. Όπως είπε συνοπτικά ο Kullmann,

σύμφωνα με αυτήν την [νεοαναλυτική] προσέγγιση, ορισμένα μοτίβα απαντώμενα στον Όμηρο ελήφθησαν από την παλαιότερη ποίηση.

και έτσι

...τα συμφραζόμενα των Κύκλιων επών φαίνεται να είναι πιο αρχαία και πιο κοντά στους θρύλους των προφορικών αοιδών από το περιεχόμενο της Ιλιάδας.

[NOTE160]. George 2010, pp. 1-2.

[NOTE162]. George 2010, p. 6.

[NOTE164]. George 2010, p. 4.

[NOTE165]. Nissen 2016, p. 34.

[NOTE165a]. Nissen 2016, p. 48.

[NOTE166]. Κονιδάρης 2021, σημ. 189.

[NOTE168]. George 2010, p. 1.

[NOTE169]. Blenkisopp 1975, p. 203. Παραθέτουμε εδώ το σχετικό απόσπασμα εν πρωτοτύπω και σε δική μου μετάφραση!

Whatever etiological factors may have gone into Gilgamesh, it is clear at any rate that it comes from a "hot" society whose scribal tradition laid the bases for Western historiography, with its immediate forebears in Israel and early Christian writers. While this may serve to illustrate Levi-Strauss' point about writing as an instrument of oppression and control[7] (we recall that Gilgamesh was discovered in a library founded by Sargon II, one of the great oppressors of antiquity) it also explains why his method cannot easily be followed here, and also, incidentally, why Leach's application of the same method to biblical material was doomed to failure.[8] The point will be made more forcibly if we go on to suggest that the preoccupation with this dimension of irreversible time leads into the central theme of the work. King Gilgamesh is exemplar of man as achiever and self-creator; he is the anthropological paradigm, the explorer of the outer limits.

Όποιοι αιτιολογικοί παράγοντες και αν συνέβαλαν στο Gilgamesh, είναι οπωσδήποτε σαφές ότι προέρχεται από μια «καυτή» κοινωνία της οποίας η συγγραφική παράδοση έθεσε τις βάσεις για την δυτική ιστοριογραφία, με τους άμεσους προγόνους της στο Ισραήλ και τους πρώτους χριστιανούς συγγραφείς. Αν και αυτό μπορεί να χρησιμεύσει για να καταδείξει την άποψη του Levi-Strauss σχετικά με τη γραφή ως οργάνου καταπιέσεως και ελέγχου[7] (υπενθυμίζουμε ότι ο Gilgamesh ανακαλύφθηκε σε μια βιβλιοθήκη που ιδρύθηκε από τον Sargon II, έναν από τους μεγάλους καταπιεστές της αρχαιότητας), εξηγεί επίσης γιατί Η μέθοδός του δεν μπορεί εύκολα να ακολουθηθεί εδώ, και επίσης, παρεμπιπτόντως, γιατί η εφαρμογή της ίδιας μεθόδου από τον Leach στο βιβλικό υλικό ήταν καταδικασμένη σε αποτυχία.[8] Το θέμα θα γίνει πιο δυναμικά αν συνεχίσουμε να προτείνουμε ότι η ενασχόληση με αυτή τη διάσταση του μη αναστρέψιμου χρόνου οδηγεί στο κεντρικό θέμα του έργου. Ο βασιλιάς Gilgamesh είναι παράδειγμα ανθρώπου ως πετυχημένου και αυτοδημιουργού. είναι το ανθρωπολογικό παράδειγμα, ο εξερευνητής των εξωτερικών ορίων.

[NOTE169a]. Nagy 1996. Το σχετικό απόσπασμα ακολουθεί:

One such example comes from the era of Peisistratos and his sons, tyrants at Athens in the second half of the sixth century BCE: from various reports, we see that this dynasty of the Peisistratidai maintained political power at least in part by way of controlling poetry.[2] {Nagy 1990a:158–162; also 75–76n114, with reference to Aloni 1986:120–123; cf. Catenacci 1993:8n2. Also Shapiro 1990 / 1992 / 1993.}One report in particular is worthy of mention here: according to Herodotus, the Peisistratidai possessed manuscripts of oracular poetry, which they stored on the acropolis of Athens (5.90.2).[3] I draw attention to a word used by Herodotus in this context, kéktēmai {65|66} ‘possess’, in referring to the tyrants’ possession of poetry. As I have argued elsewhere, “the possession of poetry was a primary sign of the tyrant’s wealth, power, and prestige.” [4] We may recall in this context the claim in Athenaeus 3a, that the first Hellenes to possess “libraries” were the tyrants Polykrates of Samos and Peisistratos of Athens.

[NOTE170]. George 2001, pp. 54-70; George 2003, p. 57. Αναφέρεται από την Jean (Jean 2014, n. 2).

ΒΙΒΛΙΟΓΡΑΦΙΑ

https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/1603/1/George%20Babylonian%20Gilgamesh%201.pdf

George, A. R. 2001. The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic I, Oxford Univ. Press.

https://cosmos.art/content/media/pages/library/the-epic-of-gilgamesh/89e2bab851-1598904500/gilgamesh.pdf

George, A. R. 1999. The Epic of Gilgamesh. A new Translation, Penguin.

https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/view/34632651/the-gilgamesh-epic-and-homer-gerald-k-gresseth-the-classical-

Gresseth, G. K. 1975. "The Gilgamesh epic and Homer," Classical Journal 70, pp. 1-18.

Moran, W. L. 1991. "The Epic of Gilgamesh: a document of ancient humanism," Bulletin of the Canadian Society for Mesopotamian Studies 22, pp. 15-22.

https://www.persee.fr/docAsPDF/arnil_1161-0492_2016_num_26_1_1102.pdf

Nissen, H.-J. 2016. "Uruk: Early Administration Practices and the Development of Proto-Cuneiform Writing," Archéo-Nil 26, 2016, pp. 33-48.

https://books.google.gr/books?id=CnkfePdtCI4C&pg=PA4&lpg=PA4&dq=The+Sumerian+poems+report+some+of+the+same+legends+and+themes+as+parts+of+the+Babylonian+poem,+but+they+are+independent+compositions+and+do+not+form+a+literary+whole.+The+Sumerian+and+Babylonian+poems+shared+more+than+just+a+common+literary+inheritance,+whether+that+was+oral+(as+seems+likely)+or+written&source=bl&ots=RvpKn-z5sO&sig=ACfU3U2E9QUfk9F6JE_nGADgaKs1CS7JvA&hl=el&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiS7vCf96H3AhWCjqQKHUDUB2AQ6AF6BAgoEAM#v=onepage&q=The%20Sumerian%20poems%20report%20some%20of%20the%20same%20legends%20and%20themes%20as%20parts%20of%20the%20Babylonian%20poem%2C%20but%20they%20are%20independent%20compositions%20and%20do%20not%20form%20a%20literary%20whole.%20The%20Sumerian%20and%20Babylonian%20poems%20shared%20more%20than%20just%20a%20common%20literary%20inheritance%2C%20whether%20that%20was%20oral%20(as%20seems%20likely)%20or%20written&f=false

George, A. R. 2010. "The Epic of Gilgamesh," in The Cambridge Companion to the Epic, ed. C. Bates, Cambridge University Press, pp. 1-12.

George 2010 <https://hozir.org/chapterid-9780521880947c01.html>

https://www.jstor.org/stable/25182268

Dalley, S. 1991. "Gilgamesh in the Arabian Nights," Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (Third Series) 1 (1), pp. 1-17.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/41177956

Blenkisopp, J. 1975. "The Search for the Prickly Plant: Structure and Function in the Gilgamesh Epic," Soundings: An Interdisciplinary Journal 58 (2), Structuralism: An Interdisciplinary Study (Summer 1975), pp. 200-220.

https://mprl-series.mpg.de/proceedings/7/6/index.html#fn2

https://www.academia.edu/71526333/The_Tale_of_the_Wild_Man_and_the_Courtesan_in_India_and_Mesopotamia_The_Seductions_of_R_s_yas_r_nga_in_the_Maha_bha_rata_and_Enkidu_in_the_Epic_of_Gilgamesh

Abusch, T., and E. West. 2014. "The Tale of the Wild Man and the Courtesan in India and Mesopotamia: The Seductions of Ṛśyaśṛnga in the Mahābhārata and Enkidu in the Epic of Gilgamesh," MELAMMU, Max Planck Research Library for the History and Developmentof Knowledge Proceedings 7, in Melammu: The Ancient World in an Age of Globalization, ed. M. J. Geller, pp. 69-109.

https://www.reed.edu/reed-magazine/articles/2017/gilgamesh-humanities-110-lecture.html

Lydgate, C. 2017. "Is Gilgamesh Relevant? Prof. Nathalia King, N. gives epic Hum 110 lecture on empire, war, and the relevance of ancient cultures," Reed Magazine, <https://www.reed.edu/reed-magazine/articles/2017/gilgamesh-humanities-110-lecture.html> (21 April 2022).

https://www.academia.edu/30930247/_The_Epic_of_Gilgamesh_and_the_Homeric_Epics_in_Melammu_Symposia_II_Mythology_and_Mythologies_Methodological_Approaches_to_Intercultural_Influences_ed_R_M_Whiting_Helsinki_University_of_Helsinki_Press_2001_pp_1_6

Abusch, T. 2001. "The Epic of Gilgamesh and the Homeric Epics," in Melammu Symposia II: Mythology and Mythologies: Methodological Approaches to Intercultural Influences, ed. R. M. Whiting, Helsinki (University of Helsinki Press), pp. 1-6.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/from-hittite-to-homer/gilgamesh-at-hattusa-written-texts-and-oral-traditions/6A752DF85607189978C9BACD9E47C90C

Bachvarova, M. R. 2016."Gilgamesh at Hattusa: written texts and oral traditions," in From Hittite to Homer. The Anatolian Background of Ancient Greek Epic, Cambridge University Press.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/602163?read-now=1&seq=10#page_scan_tab_contents

Buccellati, G. 1981. "Wisdom and Not: The Case of Mesopotamia," Journal of the American Oriental Society 101 (1), pp. 35-47.

https://chs.harvard.edu/chapter/3-homer-and-the-evolution-of-a-homeric-text/

http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Nagy.Homeric_Questions.1996

https://chs.harvard.edu/chapter/3-homer-and-the-evolution-of-a-homeric-text/

Nagy, G. 1996. Homeric Questions, Texas Univ. Press.

Nagy, G. 1990a. Pindar’s Homer: The Lyric Possession of an Epic Past. Baltimore. Revised paperback version 1994.

Aloni, A. 1986. Tradizioni arcaiche della Troade e composizione dell’ Iliade. Milan.

https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/GERI/article/view/GERI8888120288B/14795

https://books.google.gr/books?id=4771DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA303&lpg=PA303&dq=Aloni,+A.+1986.+Tradizioni+arcaiche+della+Troade+e+composizione+dell%E2%80%99+Iliade&source=bl&ots=2RSCLrD7DT&sig=ACfU3U2YzwPp_umOurMz_9yNwm8Mz3A4dQ&hl=el&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjg_8_a5q73AhXFg_0HHY0mBA04ChDoAXoECBcQAw#v=onepage&q=Aloni%2C%20A.%201986.%20Tradizioni%20arcaiche%20della%20Troade%20e%20composizione%20dell%E2%80%99%20Iliade&f=false

Stelow, A. R. 2020. Menelaus in the Archaic Period: Not Quite the Best of the Achaeans, Oxford.

https://eclass.upatras.gr/modules/document/file.php/LIT1883/00.%20%CE%91%CE%BD%CE%BF%CE%B9%CE%BA%CF%84%CE%AC%20%CE%A8%CE%B7%CF%86%CE%B9%CE%B1%CE%BA%CE%AC%20%CE%9C%CE%B1%CE%B8%CE%AE%CE%BC%CE%B1%CF%84%CE%B1/2.%20%CE%99%CF%83%CF%84%CE%BF%CF%81%CE%AF%CE%B1%20%CF%84%CE%B7%CF%82%20%CE%BF%CE%BC%CE%B7%CF%81%CE%B9%CE%BA%CE%AE%CF%82%20%CE%AD%CF%81%CE%B5%CF%85%CE%BD%CE%B1%CF%82.pdf

Καρακάντζα, Ευφ. . Αρχαϊκό έπος: Όμηρος. Ενότητα 2: Ιστορία της ομηρικής έρευνας, Πανεπιστήμιο Πατρών.

Μαρωνίτης, Δ. Ν., Λ. Πόλκας, Κ. Τουλούμης. "Αρχαϊκή Επική Ποίηση," <https://www.greek-language.gr/digitalResources/ancient_greek/encyclopedia/epic/page_062.html> (26 Απριλίου 2022).

https://chs.harvard.edu/chapter/part-i-the-hellenization-of-indo-european-poeticschapter-1-homer-and-comparative-mythology-pp-7-17/

https://dokumen.pub/greek-mythology-and-poetics-9781501732027.html

Gregory Nagy, G. 1992. Greek Mythology and Poetics (Myth and Poetics), Cornell Univ. Press.

https://www.academia.edu/355137/1997_Cline_Achilles_in_Anatolia_article?auto=download&email_work_card=download-paper

Cline, Ε. Η. 1997. “Crossing Achilles in Anatolia: Myth, History, and the Assuwa Rebellion,” in Crossing Boundaries and Linking Horizons. Studies in Honor of Michael C. Astour on His 80th Birthday, ed. G. D. Young, M. W. Chavalas, and R. E. Averbeck, Bethesda, pp. 189-210.

https://www.academia.edu/44831890/HERACLES_CATALOGUE_FIRST_PAGES?auto=download&email_work_card=download-paper

Κακαβάς, Γ. 2018. "Ηρακλής. Οικουμενικός θεός και ήρωας," από το Ηρακλής. Ήρως διαχρονικός και Αιώνιος (Νομισματικό Μουσείο), επ. Γ. Κακαβάς, Αθήνα, σελ. 127-136.

https://www.academia.edu/34579548/Galleries_and_Works_of_the_MIHO_MUSEUM?fbclid=IwAR0hN4BPSSSoaB0QRVA87Ixfl2w0VM-ICG3OwS_EMgpklBvbsV7AXFdkAk8

Hajime Inagaki. 2019. Galleries and Works of the MIHO MUSEUM, Japan

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Dietrich, B.C. 1994. “Theology and Theophany in Homer and Minoan Crete,” Kernos 7, pp. 59-74.

http://kernos.revues.org/1096

Πολλή δουλειά έχει γίνει πρόσφατα με αντικείμενο την σύγκριση των επικών στερεοτυπικών τεχνικών με τις Μινωικές εικαστικές μορφές τόσον στην τοιχογραφία όσον και στην γλυπτική.11 Οι επαναλαμβανόμενες φράσεις και επίθετα στην προφορική ποίηση παραπέμπουν σε τυποποιημένους και σταθερούς τύπους συνθέσεως της Μινωικής εικονογραφίας όπως αυτή απαντάται στην τοιχογραφία και ιδιαίτερα σε δαχτυλίδια της ΜΕΧ και της ΥΕΧ, τα οποία διακοσμούνται με ένα περιορισμένο θεματολόγιο σχεδίων, εικονιστικών στάσεων και εικονογραφικών συμβόλων.12 Τόσον ο Αιγαίος καλλιτέχνης όσον και ο επικός ποιητής εργάστηκαν με κοινά θέματα: την τειχιοσκοπία, το κυνήγι λεόντων, με συνδυασμούς πολεμικών και ποιμαντικών συνθέσεων (σκηνών-σκηνικών), με τοπία και τα παρόμοια. Τοποθετημένα δίπλα-δίπλα, τέτοια στερεοτυπικά στοιχεία παρήγαγαν συνεχείς (στον χρόνο) αφηγηματικές σκηνές, όπως στις μικρογραφική τοιχογραφία της Δυτικής Οικίας στην Θήρα.13-

-- --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://grbs.library.duke.edu/index.php/grbs/article/download/15707/6883/18323

Kelder, J. M. and M. Poelwijk. 2016. "The Wanassa and the Damokoro: A New Interpretation of a Linear B Text from Pylos," Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 56, pp. 572–584.

.. e. This view may

find support in Younger’s identification of the first line of Ta

711 as a dactylic hexameter, which may have served to stress

the gravitas of the occasion—and of those involved.10 {10 J. Younger, in S. Morris and R. Laffineur, EPOS. Reconsidering Greek Epic

and Aegean Bronze Age Archaeology (Liège/Austin 2007) 85. Note that Younger

also identifies the heading of PY Un 03, which refers to the initiation(?) of

the wanax (again an important event), as a dactylic hexameter. Younger’s

suggestion is not without problems, however. Lucien van Beek (pers.

comm.) noted that the identification of the first line of Ta 711as a dactylic

hexameter “not only stretches the concept of dactylic hexameter to the

utmost (admitting e.g. a general apocope of final vowels, which is not found

in Homer), but also allows for linguistic developments otherwise unattested

for the Mycenaean period, e.g. neglect of digamma. Finally, it ignores the

fact that the Homeric form of Augeias is not a dactyl, but molossus–shaped

(three long syllables).”}

..

https://www.academia.edu/669547/_The_metrical_evidence_for_pre_Mycenaean_hexameter_epic_reconsidered_

Maslov, B. 2011. "The metrical evidence for pre-Mycenaean hexameter epic reconsidered,"

Indoevropeiskoe iazykoznanie i klassicheskaia filologiia 15, pp. 376-389.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/kadm.1990.29.1.84/pdf?srsltid=AfmBOoq7D9bOuhbrph4fQdY1RLbmS86SeECtEpZF4rL5cPnbakyafdSN

MITTEILUNGEN: The Third International Congress on Santorini (Thera),

Kadmos 29 (1) , pp. 84-88.In the Festschrift Gimbutas, Professor Calverts Watkins writes (pp. 286 — 298) {Watkins, C. 1987. “Linguistic and Archaeological Light on Some Homeric Formulas,” in Proto-Indo-European: The Archeology of a Linguistic Problem. Studies in Honor of Marija Gimbutas, ed. N. Skomal and E. Polomé 1987, pp. 286–298.} on Linguistic and archaeological light on some Homeric formulas. Referring to the passage in the Catalogue of Ships which deals with Crete (Il.2.654—651), EPOS ..

https://archive.org/details/theraaegeanworld0001unse/page/286/mode/2up?q=Watkins&view=theater

----------------------------

https://www.ebl.lmu.de/corpus/L/1/4

electronic Babylonian library, I.4 Poem of Gilgameš

https://books.openbookpublishers.com/10.11647/obp.0250.01.pdf

Koller, A. 2021. "The Alphabetic Revolution, Writing Systems, and Scribal Training in Ancient Israel," in New Perspectives in Biblical and Rabbinic Hebrew, ed. A. D. Hornkohl and G. Khan, pp. 1–28.

σελιδα 5 ΚΛΠ.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349608400_Emotion_and_the_Ancient_Arts-_Visualizing_Materializing_and_Producing_States_of_Being

Sonik, K. 2017. “Emotion and the Ancient Arts: Visualizing, Materializing, and Producing States of

Being,” in Visualizing Emotions in the Ancient Near East, ed. Sara Kipfer, Göttingen, pp. 219-261.

https://faculty.washington.edu/snoegel/PDFs/articles/Noegel%2050%20-%20BCGR%202007.pdf

Noegel, S. B. 2006. "Greek Religion and the Ancient Near East," in The Blackwell Companion to Greek Religion, ed. D. Ogden, London, pp. 21-37.

https://mega.nz/file/FQIVnCgS#3SanHwn1Ai4MsecDA-6Qh5sL8mIL8vxISMTqVEgr6jo

Tigay, J. H. 2002. The Evolution Of The Gilgamesh Epic, Wauconda.

https://edizionicafoscari.unive.it/it/edizioni4/libri/978-88-6969-776-0/proverbs-and-gnomai-in-the-epic-of-gilgamesh/

https://edizionicafoscari.unive.it/media/pdf/books/978-88-6969-776-0/978-88-6969-776-0-ch-13_zttmy2o.pdf

Ballesteros, B. 2023. "Proverbs and Gnōmai in the Epic of Gilgamesh," in Wisdom Between East and West: Mesopotamia, Greece and Beyond, ed. F. Sironi and M. Viano, pp. 235-270.

Αυτό το δοκίμιο συζητά παροιμιώδεις εκφράσεις και σοφά ρητά στην παράδοση του Γκιλγκαμές. Υποστηρίζει ότι ορισμένες κριτικές στρατηγικές που αναπτύχθηκαν για την αρχαία ελληνική ποίηση μπορούν να εφαρμοστούν στο βαβυλωνιακό έπος, ιδιαίτερα η ανάλυση των ποιητικών γνωμών και της αφηγηματικής ειρωνείας. Ξεκινάω απομονώνοντας τον τύπο της έκφρασης, βασιζόμενος σε μια ευελιξία στους επιστημονικούς ορισμούς των παροιμιών, των γνωμών και των ρήσεων που ανάγεται στην αρχαιότητα (§ 2). Ο πυρήνας της εργασίας (§§ 3-5) διαγράφει γραφήματα και σχολιάζει σοφά ρητά στο Πρότυπο Βαβυλωνιακό (SB) Gilgamesh της πρώτης χιλιετίας με αναφορά στην προηγούμενη ποιητική παράδοση. Μετά από ορισμένες καταληκτικές παρατηρήσεις (§ 6), περιλαμβάνω μια ένδειξη πιθανών συγκριτικών οδών που αφορούν το ομηρικό έπος (§ 7).

--------

https://www.bloomsburycollections.com/app/downloadpdf?type=monograph&xmlPath=collections/29/content-types/xml//9781350297425_txt_xml.xml&xsltPath=/content-types/monograph/monograph-download.xsl&productLogo=bloomsbury_assets/collections/images/BDR_Blue_Logo_Transparent_Background.png&mlaCitation=&lang=en&documentId=b-9781350297425¤tTime=Mon%20Nov%2018%202024%2008:27:43%20%CE%A7%CE%B5%CE%B9%CE%BC%CE%B5%CF%81%CE%B9%CE%BD%CE%AE%20%CF%8E%CF%81%CE%B1%20%CE%91%CE%BD%CE%B1%CF%84%CE%BF%CE%BB%CE%B9%CE%BA%CE%AE%CF%82%20%CE%95%CF%85%CF%81%CF%8E%CF%80%CE%B7%CF%82&tocId=b-9781350297425&productName=collections&citationExist=true&workloc=$workPath&territory=GR&cachepagetype=mono&tocPage=true&epdfIsbn=9781350297173&docIdS=b-9781350297425&openAccess=true

https://www.bloomsburycollections.com/monograph?docid=b-9781350297425&st=Enuma+Elish

Haubold, J., S. Helle, E. Jiménez and S. Wisnom, eds. 2024. Enuma Elish: The Babylonian Epic of Creation, Blumsbury Collections.

https://www.academia.edu/125156982/A_Tale_of_Two_Heroes_A_Shared_Story_Pattern_in_the_Iliad_and_the_Mah%C4%81bh%C4%81rata

https://www.jiesonline.com/issues/

Doda, A. 2023. "A Tale of Two Heroes: A Shared Story Pattern in the Iliad and the Mahābhārata," Journal of Indo-European Studies 51 (1 & 2), pp. 1-33.

p. 23

It is now important to consider the other great epic tradition to which the Patroclus-Achilles story-pattern has been linked. Unlike the Mahābhārata, scholars have spent gallons of ink on the Iliad’s relationship with the Near Eastern epic of Gilgameš, specifically drawing a comparison between the eponymous hero and his friend Enkidu on one side, and Achilles and Patroclus on the other.47 Martin West has discussed in detail the similarities between the characters and their narratives (1997: 336-347). His analysis makes clear that, at least on a general level, the resemblance is undeniable: the epic’s main hero loses his closest friend and, after sorely lamenting him, he embarks on a course of action that will lead him to acquire a deeper understanding of his mortality.48 Certain parallels are admittedly detailed and impressive: the grief of both Achilles and Gilgameš is compared to that of a lioness deprived of her cubs (Il. 18.318- 323 and SBV 49 VIII.59-62),50 and both heroes have an encounter [NEXT PAGE IS 24] with the ghost of their dead friend (Achilles in a dream at Il. 23.65-69, and Gilgameš in his journey to the Underworld, SBV XII.85-89).51 In addition, Michael Clarke has discussed the theme of the substitute: on the basis of the term pūḫu (‘substitute’, used of Enkidu at SBV II.110), he speculates on a possible connection with the ancient Mesopotamian ritual of royal substitution (šar pūḫi), whereby the king was replaced by a subject (who wore his garments and accoutrements) when threatened by the visitation of ill-omened dreams.52 This could be significant in connection with Patroclus, who dons Achilles’ armour in Book 16.[53]

No one would deny categorically that these resemblances exist. However, one cannot help having the feeling that Classical scholars have built too much on these foundations. Lord, for one, describes Enkidu as “the closest parallel to Patroclus” (2019: 207).

Martin West goes as far as to define the Gilgameš epic as “the source version” for the Iliad,[54] as though Homer had a model text on which to draw. Van Nortwick correctly writes that “looking at Achilles and Patroclus will immediately remind us of Gilgamesh and Enkidu”, but then goes on to say that “this is almost certainly not evidence of any conscious reminiscence, but rather of how deeply embedded the story pattern is in the mythical substratum of the Mediterranean and the Near East” (1992: 40).

If this story-pattern is embedded anywhere, I would suggest that its original substratum is to be found in the Graeco-Aryan (if not Indo-European) tradition. The evidence gathered in our discussion seems to point in that direction: not only are the correspondences between the Iliad and the Mahābhārata more numerous and detailed, but the Gilgameš epic lacks some crucial events that mark the narrative of Patroclus’ death (and its aftermath). First of all, the main hero Gilgameš is never absent from the scene (as Achilles and Arjuna are in their respective epics) and does not dispatch his substitute on a mission. Martin West cites the parallel of another Near Eastern poem, Gilgameš and Agga, where the hero bids Enkidu make a sortie to fight back..

p. 26

The original pattern, therefore, is more likely to be traced back to the PIE or Graeco-Aryan tradition, since the correspondences between Abhimanyu and Patroclus outdo in both quantity and quality those between Patroclus and Enkidu.61

This, of course, does not necessarily mean that the Near Eastern epic exerted no influence on Homer’s adaptation of this narrative pattern: we should avoid casting this kind of literary comparisons as an ‘either-or’ question. It is quite plausible that the poet has selected a few significant details of the Gilgameš [NEXT PAGE IS 27] myth (e.g. the lion simile or the ghost scene) and adapted them to the closest possible narrative sequence that his own tradition provided.62 Borrowing terms from the realm of textual criticism, we should remember that independent inheritance and horizontal transmission are not mutually exclusive. In conclusion, the detailed resemblance with the Mahābhārata suggests that the Iliad poet inherited the bulk of this story pattern from the Graeco-Aryan tradition and then further developed it with Near Eastern motifs.63

[1]. More recently Stephanie Jamison has shown convincingly that the τειχοσκοπία in Il. 3, when compared to the scene of Draupadī’s abduction by Jayadratha (MBh. 3.252-256), bears the traces of an ancient Indo-European societal institution (1994), and has further compared motifs and patterns from the Mahābhārata and the second half of the Odyssey (1999). Emily West’s work has unearthed several narrative parallels between the two epics and contributed decisively to the reconstruction of a Graeco-

Aryan proto-epic: to cite only a handful of examples, she has identified important connections between the Cyclops episode in Od. 9 and the episodes with Baka (MBh. 1.148-152) and Kirmīra (3.12-30) in the Indian epic (2004); between Diomedes’ ἀριστεία (Il. 5) and Bhīṣma’s duel with Rāma Jāmadagnya

at MBh. 5.179-186 (2006); and between the female characters of Circe and Calypso on the Greek front and Hiḍimbā on the Sanskrit front (2014).

Furthermore, detailed comparisons between the night raids in Il. 10 and MBh.11 have been successfully carried out by Kathleen Garbutt (2006) and Almut Fries (2016).

https://www.mprl-series.mpg.de/proceedings/7/7/index.html

Jean, C. 2014. "Globalization in Literature: Re-Examining the Gilgameš Affair," in Melammu: The Ancient World in an Age of Globalization, Berlin: Max-Planck-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften.

https://www.aegeussociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Sugawara-Gilgamesh-Iliad-5Ag18-1.pdf

https://thesis.ekt.gr/thesisBookReader/id/22086?lang=el#page/8/mode/2up

Sugawara, Chikako. 2008. "Athena in arms: the city-goddess of Athens" (diss. Univ. of Athens).

Κονιδάρης, Δ. Ν. 2021. Ιστορία των θετικών τεχνών και επιστημών κατά την Αρχαιότητα: αποσιώπηση και μεροληψία, Αθήνα.

FEATURED EXHIBITION. Mesopotamia, Civilization Begins (OR NOT?), April 21–August 16, 2021, GETTY VILLA

Mesopotamia: Civilization Begins; First Cities

Mesopotamia: Civilization Begins; First Writing

West, E. B. 2004. "An Indic reflex of the Homeric Cyclopeia," Classical Journal 101, pp. 125-160.

The Homeric Cyclopeia has long been understood to be native to the folk tale, rather than the epic, tradition. This article suggests that a set of episodes from the Sanskrit epic Mahabharata may provide not only a better hypothesis for the origins of the tale, but a compelling explanation of its meaning, The Mahabhzirata's three scenes describing combat with ogres appear to have been constructed upon the same underlying tale as the Cyclopeia, and their narrative commonalities are supported by philological evidence as well. The comparison ultimately suggests that the story derives from Indo-European ritual and friction between the warrior and priestly classes.

https://kypseli.ouc.ac.cy/bitstream/handle/11128/5164/%CE%95%CE%93%CE%9B-2022-00126.pdf?bitstreamId=a32240db-774a-424c-89e6-f0a166cf9ab9&locale-attribute=el

Γουσόπουλος, Δ. 2022. "Ο μύθος του Κύκλωπα Πολύφημου από την προιστορική εποχή και την ΙΕ παράδοση ως και την παγίωση του Ομηρικού αρχετύπου" (διδ. διατριβή Ανοικτό Παν. Κύπρου)

https://www.scribd.com/document/905250058/Ebook-Philosophy-before-the-Greeks-The-Pursuit-of-Truth-in-Ancient-Babylonia-by-Marc-Van-De-Mieroop-ISBN-9781400874118-online-reading

Philosophy before the Greeks: The Pursuit of Truth in Ancient Babylonia by Marc Van De Mieroop

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/400906308_E_ISTORIA_TOU_GILGAMESH_eranismata_scholia

DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.14271.98725